“ACCESSORIES OF HOLINESS”: DEFINING JEWISH SACRED OBJECTSVIRGINIA GREENE

ABSTRACT—An attempt to apply a current definition of Native American sacred objects to material from another culture and religion reveals the inadequacy of a broad-based definition as a guide to the appropriate handling of sacred objects in a museum setting. These guidelines must be established individually for each culture, religion, or tribal group. Traditional Judaism divides ritual objects into two main categories, those that carry a quality of holiness; and those that are essential to the performance of a particular ritual or commandment but that have no intrinsic quality that can be defined as sacred or holy. Once they are no longer in ritual use, only some of the objects in the first category should be treated differently from the way other museum collections are treated. For these pieces, repair or restoration done by a conservator is inappropriate. For almost all other objects, conservation, repair, or restoration can be carried out without restriction. 1 INTRODUCTIONRecent congressional legislation on the repatriation of Native American material defines sacred objects as “specific ceremonial objects which are needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents ” (U.S. Congress 1990). This definition might be understood to imply that all objects needed for a ceremony are also sacred, thus requiring special consideration when treated by a conservator. This is not always the case even for Native American groups (Ladd 1991), and the definition certainly cannot be applied wholesale to other religions and cultures. The statement also implies the presence or participation of a religious leader when the objects are used, an implication that further restricts the applicability of the definition. Traditional Judaism recognizes two categories of ritual objects: those that carry a quality of holiness and those that are essenital to the performance of a particular ritual or commandment but have no intrinsic quality that can be defined as “sacred” or “holy.”1 This classification was specifically designed to answer two questions: Which objects used in a ritual context may also be used for secular purposes? What should be done with ritual objects when they are no longer fit for use? The first question is largely of academic interest, at least at the present time. The second, however is a practical problem of considerable importance. The classification also provides a foundation for decisions about the conservation of these objects. 2 HOLY OBJECTSThe first category of ritual objects is called tashmishey kedusha, “accessories of holiness” or “objects which carry holiness.” The classic example is a Torah scroll. This is so obvious that it is not even mentioned in the texts. The category also includes:

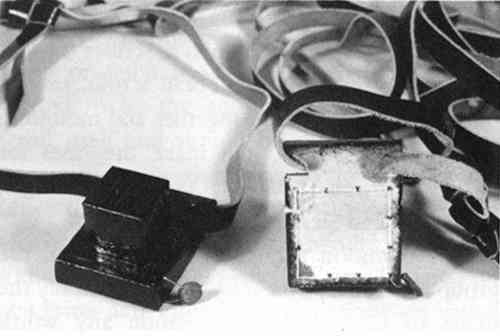

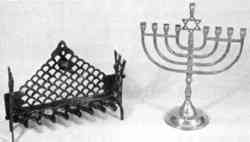

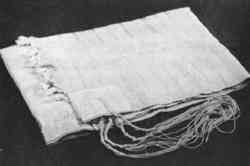

The three written texts, the Torah scroll, tefillin, and klaf for the mezuzza, form the core of this category. All are, or contain, biblical texts that must be handwritten on parchment, in a The common feature of the objects in the group is that they contain words, specifically the name of God, but by extension any words divinely written or inspired, from which the quality of holiness is derived. The nontextual objects all come into intimate contact with the texts, and in so doing acquire some of the same quality of holiness. The transmission is not indefinite, however, extending a maximum of two layers. For example, curtains located outside of the ark curtain itself are not affected. Over the years, this category has been expanded to include not only other handwritten biblical texts (such as the Scroll of Esther) but also printed Bibles, prayer books, volumes of the Talmud, law codes, and commentaries, not only in Hebrew but in other languages as well. In some communities, any document of any kind written in Hebrew letters was included; the holy quality of the Hebrew language extending to other languages, such as Yiddish, written with the same alphabet. According to the Shulchan Arukh (see note 1), tashmishey kedusha, when no longer fit for ritual use, must be “put away” (O.H. 154.3; Mishneh Torah, II 10.3). Traditionally, Ashkenazic Jews fulfill this requirement through burial, either in a specific part of a Jewish cemetery or, in some localities, next to or along with a man of exceptional piety and learning. Many Sephardic/Oriental Jewish communities put tashmishey kedusha in a special room in the synagogue, called a geniza (from the root meaning “conceal,” “hide,” or “preserve”). Because of the extension of the category to include handwritten and printed books and documents along with the traditional items, these storerooms often contained a great deal of material. The most famous geniza is in the Ezra Synagogue in Cairo. Rediscovered at the end of the 19th century, it held more than 200,000 pages, some dating to the founding of the synagogue in 882 (Milgram 1971; Encyclopedia Judaica 1971), 7:404. Once tashmishey kedusha have passed out of the traditional community and into the care of a museum, they can be further divided into two groups: (1) Torah scrolls, tefillin (both cases and texts), and the scroll (klaf) inside the mezuzza; and (2) all other material, including printed or handwritten documents, Torah mantles, ark curtains, tefillin bags, Torah ornaments, and mezuzza cases. Objects in group (2) may be treated by any qualified conservator. In all cases it is preferable to treat Jewish ritual material as anthropological material rather than as art, keeping conservation treatment to a minimum and avoiding extensive restoration, but any ethical treatment is permitted. Conservators in private practice, who may not have the option of minimal treatment, may have to take on greater responsibility as a result. Original fabric or trimming removed from an ark curtain, for example, should be given to the owner for proper disposal. If the owner is unwilling to do this, it becomes the responsibility of the conservator to make the arrangements.3 Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzza scrolls should be left as they are. Once they are no longer in use, there is no reason for them to be kosher—in proper condition to be used—and therefore no reason why missing or abraded letters should be restored or minor repairs made to the parchment. As the texts of these documents never vary and they are never illustrated, aesthetic considerations are not relevant. If, for the safety of a Torah scroll, it is determined that repairs must be done to the rollers on which the scroll is mounted, these repairs shou be done by a scribe, who will then remount the parchment onto the roller in the traditional manner. A Torah scroll that has a tear in the parchment can be kept rolled to another part of the scroll. If two pages are separated, the two parts of the scroll should be wrapped and stored separately. If it is considered both possible (considering the condition of the parchment) and essential to rejoin the separated leaves, this work should be done only by a scribe. While they are in use, a pair of tefillin must be opened and examined periodically by a scribe to ensure that they are still ritually fit. Once they are no longer in ritual use, they should be left as they are. Undamaged tefillin should never be opened in a museum. The texts inside an already damaged pair of tefillin may be removed and examined, as the style of the writing may give clues to the time and place in which they were written. Tefillin may be exhibited in a damaged condition if there is some reason to do so, such as association with a famous person, or in an exhibit of Holocaust material. Alterations of any kind to an object that survived the Holocaust, unless absolutely necessary to ensure its physical survival, are inappropriate. Repair of other books and documents, when done with the respect that should characterize any professional conservation treatment, is entirely appropriate. In Judaism, study of traditional texts is considered to be the equivalent of prayer. To restore any text, whether of aesthetic or historical value or not, to a state in which it can be studied is an act of merit whatever the religious or cultural affiliation of the person doing the work. When Torah scrolls, Bibles, prayer books, or volumes of the Talmud are in the possession of a Jewish institution or a traditional Jew, photography (or making photocopies) of open scrolls or pages is normally permitted only for serious study or publication, as the copies are considered to be the equivalent of the book or scroll itself and should be disposed of in the same way once they are no longer needed. Once the books and other documents are in a secular library or archive, the rules of the institution apply. These rules are usually based on condition and value, but restrictions on casual copying would be appropriate in all cases. The person obtaining the copies should be informed of the proper procedures for disposal, and the institution should offer to perform this service if the person returns the material. 3 OTHER RITUAL OBJECTSThe second category of ritual objects is termed tashmishey mitzvah, “accessories of religious observance,” or, more clearly, “objects which make it possible to perform a commandment.” This category includes most other ritual object essential to Jewish life, including wine cups used on Sabbaths and holidays (fig. 8);4 the Hanukkah menorah (hanukiyah, fig. 9); seder plates used on Passover (fig. 10); the shofar (ram's horn trumpet, fig. 11); the tallit (a prayer shawl with special knotted fringes, called tzitzit, (fig. 12); the sukkah (booth), a temporary dwelling built on the holiday of Sukkot as well as the lulav (a palm branch tied together with willow and myrtle) and etrog (citron) also used on Sukkot, etrog containers; Sabbath candlesticks; the spice box and candle holder used for the Havdalah service at the end of the Sabbath; challah and matzah covers; wedding canopies.

Most of these are permanent and often passed on for generations. Those associated with Sukkot (with the exception of the etrog container) are impermanent and must be built or acquired anew each year. At the conclusion of Sukkot, the sukkah is dismantled. Though some of the Other tashmishey mitzvah may be also discarded when they are no longer fit for ritual use. If a ceramic seder plate breaks or a silver wine cup is crushed, it will be repaired (for use or display) if not too badly damaged (as any secular item of value), or if not repairable, it will be discarded and replaced. A wine-stained challah or matzah cover will be saved if embroidered by one's grandmother, discarded and replaced if a modern commercial product. A shofar, however, may not be repaired. A small chip at the bottom of the horn can be trimmed down, but if there is major damage to the mouthpiece or body of the horn it must be replaced. These objects may be discarded because they have no intrinsic quality of holiness. Great care and expense often go into their manufacture, so that they are objects of beauty (and hence of value in terms of Western aethetics), but this is a consequence of the principle of hiddur mitzvah, “enhancing a commandment” (derived from Exodus 15.2). It is desirable, for example, to have the most beautiful kiddush cup that one can afford, but if one cannot afford silver, then glass will serve, and if a fine wine glass is unavailable, then one puts the wine in a plain glass—or a Over centuries, however, customary practice has become stricter than the original law, and several of the objects in this group are now treated as tashmishey kedusha. The best example is the tallit. It is clear that merely untying the knots or cutting the cords removes all special qualities from the tzitzit (Mishneh Torah, II 8.9), and the tallit itself was not special at all, as it was originally an ordinary garment. By the 16th century, the custom had already changed. The Shulchan Arukh states that tzitzit “should be treated with the consideration due to holy objects” (Klein 1979:5, O.H. 15.1, 21.1). Today most Conservative synagogues will set aside for burial any synagogue tallit that is no longer fit to be worn, and traditional Jews will do the same with their own, as well as with a damaged shofar. These objects may be treated by any qualified objects or textiles conservator, with the same preference for minimal treatment noted above. No attempt should be made, however, to retie or replace damaged fringes on a tallit. 4 EXHIBITION AND STORAGEThere are few restrictions on the exhibit of Jewish ritual objects and generally none on the examination of this material for purposes of study by anyone of any religion or culture. Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzza scrolls are normally not exhibited unrolled, but this may be done if they are no longer fit for ritual use. In these cases, the advice of a rabbi should always be sought. These objects should be stored in a drawer or cabinet and covered. If a conservator judges it is unwise to leave an original mantle on a scroll, or a pair of tefillin in its bag, these can be separated. Small Torah scrolls may be safely stored lying down in a drawer; large ones should be kept upright in a special rack. If a scroll has no mantle, or the original one must be removed, a plain cloth mantle should be made. Small scrolls in drawers may be covered by a clean white cloth or tissue paper. Tefillin should be kept in a special bag if one exists or placed in a plain cloth bag. Mezuzzah scrolls can be kept in their cases or wrapped in tissue. If properly cared for, there is no reason why these objects, if now in good condition, should ever require conservation treatment except in the event of a disaster. If the parchment is in good condition, a Torah scroll should be completely rolled, front to back (or vice versa) and back to the center, once every year or two. This should be done only by people (it takes two) who are experienced in this procedure, with the advice of a conservator. When taken out for study, tashmisheykedusha should be treated with the same respect one would show for a similar object still in ritual use. The table on which they are placed should be covered by a clean cloth, and the objects should be covered when not being examined or read. If left for a short period of time, a Torah scroll should be rolled up and the mantle or cloth placed on top. Tefillin or mezuzzah scrolls should be similarly covered. 5 CONCLUSIONReaders are cautioned that this is a discussion paper and that I have not provided a comprehensive set of rules for the treatment of all Jewish ritual objects, only guidelines that should enable a conservator to distinguish between pieces that may be treated as ordinary, “nonsacred” material, and those objects that should not normally be subject to conservation treatment. This paper also represents primarily a Conservative point of view, with a traditional The difficulties posed by broad definitions of sacred objects should be obvious. However valid the new congressional definition as a basis for a discussion of the repatriation of Native American material, it tells us nothing about the way in which such objects, or similar material from other cultures, should be handled in a museum. For conservators to observe appropriate ethical standards in the handling of sacred material, systems of classification together with guidelines for practical application will have to be developed for each cultural, religious, or tribal group, with the assistance (wherever possible) of a member of that group. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to thank Dr. Saul Wachs, of Gratz College, and Cantor Mark Kushner, of Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel, in Philadelphia, for information and advice; Rabbi Ira Stone, of Beth Zion-Beth Israel, for translating a passage from the Shulchan Arukh; the synagogue Sisterhood for permission to photograph objects from its gift shop; and Jerry Silverman, a mensch for all seasons, who lent me (at the very last minute, without a single question) some of the slides that I used at the AIC meeting in Albuquerque. NOTES1.. Talmud, Megillah 26B; Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, II; Shulchan Arukh, O.H. 154.3. Moses Maimonides (1135–1204) was a physician, philosopher, and rabbinic scholar. The Mishneh Torah is a law code, i.e., a practical guide rather than a theoretical discusssion of legal issues. The Shulchan Arukh is a medieval law code (first published 1565) still considered authoritative by traditional Jews. 2.. Ashkenazic Jews trace their ancestry to communities in central and eastern Europe. Sephardic Jews are those who came originally from the Iberian Peninusula. After they were expelled in 1492, many settled in Greece, Turkey, and Palestine as well as in other parts of the world. Oriental Jews are those who trace their ancestry to the Arab world and Iran, as well as those whose families never left Palestine. 3.. I am indebted to Paul Himmelstein for permission to transform his experiences with owners of Torah ark curtains into a general principle. 4.. These cups are usually called kiddush cups, after the blessing over wine that is said at the beginning of every Sabbath and holiday. The word kiddush comes from the same root as kedusha, “holiness.” REFERENCESCowan, P.1986. A Torah is written. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. Encyclopedia Judaica. 1971. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House. Klein, I.1979. A guide to Jewish religious practice. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary. Ladd, E. 1991. Personal communication. Milgram, A.1971. Jewish worship. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. Ray, E.1986. Sofer: The story of a Torah scroll. Los Angeles: Torah Aura Publications. Siegel, R., M.Strassfeld, and S.Strassfeld, eds.1973. The Jewish catalogue. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

U. S. Congress. 1990. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Public Law 101–601. United States Code Congressional and Administrative News, 101st Congress–Second Session. St. Paul, Minn.: West Publishing. AUTHOR INFORMATIONVIRGINIA GREENE is senior conservator at the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Originally trained as an archaeologist (B.A. in anthropology, Barnard College, 1963; M.A. in anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, 1968), she received her diploma in the conservation of archaeological and ethnographic materials (with distinction) from the Institute of Archaeology, University of London, in 1971. She also has a B.A. in Jewish Studies from Gratz College and will receive her M.A. in Jewish studies in 1992. In addition to broad professional interests in objects conservation, museum storage, and exhibits, she is a member of the Board of Directors and Ritual Committee of Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel and often leads services or reads Torah for the congregation. Address: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 33d and Spruce Streets, Philadelphia, Pa. 19104–6324.

Section Index Section Index |