CONSERVATION TREATMENT OF TIBETAN THANGKASANN SHAFTEL

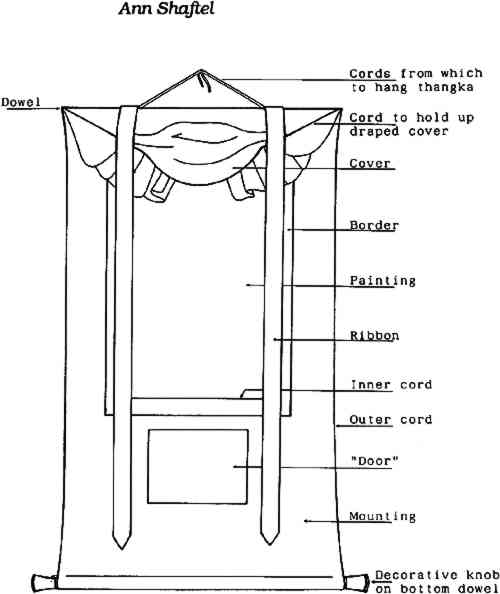

ABSTRACT—Tibetan thangkas are complex objects, with intricate iconography and technical construction. Conservators must be fully aware of a thangka's religious and cultural aspects prior to attempting treatment. A combination of media such as textile, painting, wood, and sometimes leather and metal, thangkas require a balanced approach in conservation treatment. The results of inappropriate conservation methods may well prove that the cure is worse than the disease. 1 INTRODUCTIONCOMPOSITE OBJECTS present a special challenge to the conservator. Their treatment provides fertile ground for both research and controversy, crossing the boundaries of standard categories of conservation training: painting, objects, textiles, and paper. A conservator accustomed to working in only one of these media may find it difficult to understand and adjust to a proposed treatment that involves many materials and awareness of their interaction. The difficulty is compounded when the composite object is a religious artifact and its iconography and social significance must be respected. Ideally, no aspect of treatment would compromise the original purpose of the object. To acquire and apply this attitude of respect requires extensive research into the cultural significance of the object to be treated and the materials and methods of its construction. Such research should address informants from the culture, both artists and religious authorities. Unfortunately, the time and effort required for thorough research on every object are beyond the reach of most conservators, in both private and institutional situations. The conservation treatment of a composite object with complex religious significance is therefore a formidable task. Two possibilities for error come to mind: placing foremost the needs of one of the diverse materials (e.g., painting versus textiles) or applying years of experience with objects from other cultures and drawing incorrect conclusions about the object in hand. 2 PROBLEMS IN THE CONSERVATION OF THANGKASTIBETAN THANGKAS are complex objects. A popular form of thangka might consist of a central painting (cotton support) mounted in textile borders (silk with cotton lining) that have wooden dowels on the top and bottom and sometimes protective leather corners on top edges of the mounting and decorative metal knobs on the bottom dowel (fig. 1; for a more complete description, see Shaftel 1986). A thangka is a prime example of “inherent vice.” Each material reacts differently to handling, aging, changes in temperature and humidity, and so forth.

Thangkas also have a complex religious significance and function (Trungpa 1975). The iconographic content of the picture panel is a guide to meditation. Traditionally, the teachings are passed on from teacher to student meditator. If a conservator treating a thangka is without extensive training in both iconography and painting technique, an attempt to inpaint is fraught with opportunities for error. The mounting is an inherent part of the thangka (Schoenholzer-Nichols 1988). Even when its painting has been removed and is displayed separately, it remains a painting that belongs in a thangka. In 21 years of research, I have encountered many well-intentioned mistakes in the conservation treatment of Tibetan thangkas. These include treatments that have:

When the conservator is faced with a painting long since removed from its mounting, several options are available, each presenting a possibility for error. Notable errors have been:

3 SPECIFIC EXAMPLES OF INAPPROPRIATE TREATMENTSTHE FOLLOWING examples are drawn from thangkas owned by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. The author has extensively researched these thangkas, completed conservation study, and begun conservation treatment. It should be noted that the thangkas used here as examples had been treated before they entered the collection of the museum; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is to be respected for the care of its collection. 3.1 EXAMPLE 1Gelukpa Assembly Field, 74-36/18, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Bequest of Joseph H. Heil) h. 76.2 � w. 117.5 cm; overall dimensions: h. 154 � w. 169 cm (fig. 2)

This is an example of conservation treatment in situ in its mounting. The following is a brief summary of the condition; it is not intended as a complete examination report. The mounting of this thangka is traditional and elaborate. The cover is in comparatively good condition. According to a museum employee, it was folded behind the mounting while the thangka was on exhibit continuously for 10 years. The cover is of hand-stitched silk with two panels crowned by an elaborate valence. The mounting proper has leather corners, hanging ribbons, and other traditional components. Both original dowels are missing; the bottom edge of the mounting has been trimmed off, then crudely sewn to create a new dowel sleeve. The painting support is of medium-weight plain-weave cotton. It is damaged overall with the creases and folds common to older thangka painting supports. The ground and paint layers reflect the damage to the support below. The ground was originally off-white in color and finely applied and polished. The paint layers were originally skilfully applied but are now faded, dirty, and abraded with a network of losses overall. The support has been lined on the reverse with polyvinyl acetate (PVA-AYAA) onto thin Mylar, carried out with the painting in place in its mounting. For several reasons, it cannot be considered a successful endeavor. First, the support was not flattened before lining. The creases, wrinkles, and bulges were not allowed to relax into a planar surface before the lining process. Pools of bubbled polyvinyl acetate fill irregularities in the support from behind. The polyvinyl acetate has a top surface contour similar to a landscape—with mountains, valleys, and plains. Any draws or buckles caused by the uncomfortable fit of the cotton support of the painting into the silk mounting have been reinforced. On the reverse the thin-gauge-Mylar is peeling away from the polyvinyl acetate in the proper lower right-hand corner. On the obverse, specular reflection shows glints of shiny adhesive that has come up through areas of weakness in the support. No attempt has been made to remove these, nor has any inpainting been attempted. In summary, the painting was lined in situ. The painting was not made planar prior to lining, so surface irregularities were reinforced. The Mylar lining is peeling off, and the adhesive has leaked through the support and glistens on the obverse. No treatment has been given to the mounting. This thangka has received a treatment inadequate for its preservation. Reversal and correction of the above treatment would be difficult and require extensive use of solvents. 3.2 EXAMPLE 2The Dharmapala Paldan Lhamo (Glorious Goddess) and Her Retinue 74-36/26, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Bequest of Joseph H. Heil), h. 80 � w. 57.1 cm; overall dimensions: h. 80.6 � w. 58.8 cm (fig. 3)

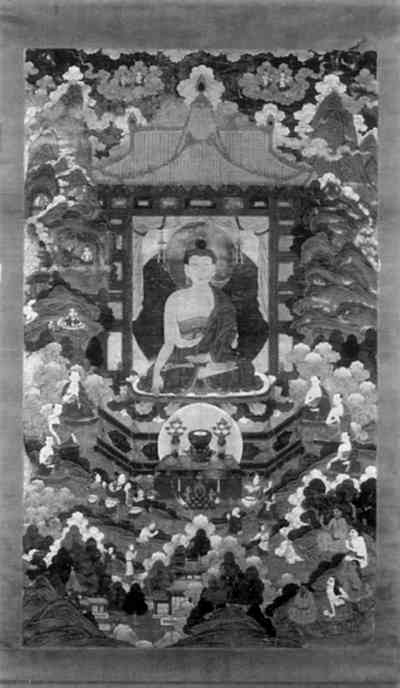

This is an example of a painting permanently separated from its mounting and lined with a “heavy hand.” The following is a brief summary of the condition. The support is medium-weight plain-weave cotton. Raking light shows a planar surface except for a 7.1 cm long crease located in the proper lower right quadrant and running diagonally. Transmitted light shows areas of former weakness in the support of a type often found in thangkas that have been rolled and handled improperly. The ground is off-white and evenly applied on both sides of the support. The background color of the composition is black, the traditional color for a painting that depicts a protector of the teachings. The ground and paint layers are secure, but the colors have a flat, dead surface from the lining process and are darkened from adhesive penetration. These colors can be contrasted to the other original colors still visible on the untreated tacking edge, which have varied textures and are lighter, and more “alive.” On the obverse, the conservator neglected to remove each thread (which originally held the painting in its mounting) before beginning the lining process. Consequently, fragments of cotton threads still remain in some of the stitch holes in the tacking edge. On the reverse, these thread fragments are partially embedded in the mounting adhesive and partially covered by the Mylar lining. This lining does not completely cover the reverse of the support but extends unevenly up to the tacking edge. This painting has been given a conservation treatment that, even if applied to a Western painting, would be inappropriate considering the results achieved. It was lined with polyvinyl acetate (PVA-AYAA) on Mylar with a brush coat of the liquid adhesive in toluene. Some of the adhesive penetrated through the ground and paint layers to the front of the painting. Then it was lined face up on a vacuum hot table with a high vacuum (24″ Hg), which created weave interference by forcing the paint film down into the weave of the support fabric. This treatment irreversibly altered the painting both physically and aesthetically. The flat quality the painting now has destroys the effect of varied textures of each type of pigment. Traditionally, some of the colors (blues and greens) would have been burnished after being applied and others, such as the traditional red, would have had a shiny surface. The flat gold and the shiny gold details in the flames and on the garments would catch the light in yet a different way. When this surface was viewed in the candlelight and butterlamp light of shrines, the surface would appear rich in texture, with flashing and glittering gold highlights. In this case, inappropriate conservation treatment has obliterated these effects. The surface has a dead, dull quality instead of a lively aspect that would express the life and power of the deities depicted. 3.3 EXAMPLE 3An Enthroned Buddha, 35-134/1, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Nelson Fund), h. 123 � w. 73 cm; overall dimensions: h. 142 � w. 84 cm (fig. 4)

This is an example of a painting removed from a thangka and remounted in China. The current mounting is thin silk on paper, Chinese style. The mounting is shredded on the outside edges of the top section. A small section of the mounting silk is missing from the proper left side panel (at the level of the Buddha's head). The proper upper left corner bears a stain. The mounting is not in traditional Tibetan style in form, color, or proportion. The painting support is a traditionally prepared plain-weave cotton cloth. From the pattern of visible damage to the ground and paint layers, one can assume that the support was creased and cockled prior to lining. Currently, the support is relatively stable with a repetitive series of bulges corresponding to the pattern as rolled. The ground and paint layers were applied in traditional manner and are currently stable but show evidence of previous damage. There is overall paint loss corresponding to former creases in the support. A second category of paint loss appears to be the result of abrasion. A third category is water damage, with total loss of paint layers in some areas. The fourth category of damage to the ground and paint layers is the direct result of the Chinese mounting process, which introduces moisture from behind and employs an aqueous adhesive. Both techniques cause the delicately applied paint layers to sink into each other. A matte and slightly blanched surface is the result. This surface is not in keeping with the original intent of the artist. In traditional Himalayan thangka painting the desired effect of a finished painting is a marked texture variation across the surface. Flat contrasts with burnished areas, thin washes contrast with more heavily applied pigments, dry shading contrasts with wet. The various sizes of particles of traditional pigments create a varied surface texture. The organic lakes used for shadow and outline are thin and fine, without a granular texture at all. The aesthetic is almost three-dimensional in its effect, not at all the flat matte, sunken surface created by a Chinese or Japanese mounting process. A thangka is not only a painting; hung properly, it creates a three-dimensional sculpture. The raised and draped cover, the ribbons hanging partially over the painting, and the finials of the bottom dowel curving out from the mounting all contribute to this effect. Even a recently made painting in its mounting does not present a perfectly planar surface, in contrast with the flat painting and mounting surfaces of Chinese and Japanese scroll paintings. Paintings similar in content to Tibetan thangkas have been created in China with Chinese aesthetics. Mountings are flat, in scroll form with paper backing. But a Tibetan creation does not take kindly the removal from its original cloth mounting and the 4 CONCLUSIONTIBETAN THANGKAS are complex in both iconography and technical construction. It is imperative that they be conserved with the whole concept in mind rather than treated part by part, each part a separate technical problem. As when dealing with other ethnographic materials, conservators dealing with Tibetan thangkas must be fully aware of their religious and cultural aspects before attempting any treatment. The results of inappropriate conservation methods may well prove that the cure is worse than the disease. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTHE AUTHOR is indebted to The Venerable Ch�gyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, and The Vajra Regent �sel Tendzin, as well as to Noedrup Rongae, master painter. The staff of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, have been most cooperative. Garry Thomson offered initial encouragement. REFERENCESJackson, D. P., and J. A.Jackson. 1984. Tibetan thangka painting: Methods & materials. London: Serindia Publications. Schoenholzer-Nichols, T.1988. Conservation of the textile frames of the THAN-KAS from the Tucci Collection, Rome. In Conservation of Far Eastern Art, ed.J. S.Mills, P.Smith, and K.Yamasaki. London: International Institute for Conservation. 83–86. Shaftel, A.1986. Notes on the technique of Tibetan thangkas. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation25:97–103. Trungpa, C.1975. Visual Dharma: The Buddhist Art of Tibet. Berkeley, Calif.: Shambhala. AUTHOR INFORMATIONANN SHAFTEL is a fellow of the American Institute for Conservation. She holds an M.S. in conservation from Winterthur (1978), an M.A. in Oriental art history from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1972), and a B.A. from Oberlin College (1969). She also studied conservation at ICCROM in 1974. She has been apprenticed to Tibetan master painters for 15 years and has been working with thangkas for 21 years. She has published and lectured on thangkas and served as a consultant and conservator for public and private collections. Address: Fine Arts Conservation, 5312 Kaye St., Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 1Y3, Canada.

Section Index Section Index |