WASHINGTON ALLSTON: POEMS, VEILS, AND “TITIAN'S DIRT”JOYCE HILL STONER

ABSTRACT—The 19th-century American artist Washington Allston used multiple glaze layers, megilp and asphaltum, and final tonings employing what the artist called “Titian's dirt.” These techniques could cause problems during later cleanings. Allston himself disclaimed authorship of one of his earlier paintings after it was cleaned. His painting The Spanish Maid, his poetry, his palette, and his color theories are also considered, primarily through study of contemporary documents and visual impact. THERE ARE at least three reasons paintings by the American artist Washington Allston (1779–1843) should be approached even more circumspectly than usual by a painting conservator: his multiple soluble glazings, his documented penchant for the use of megilp and asphaltum, and his final tonings using what he called “Titian's dirt.” Allston is not as well known in today's art world as his 19th-century admirers would have predicted. Perhaps he was too eclectic and chameleonlike in his ability to pick up and translate different styles as he attempted to bring reflections of European masterworks back to Boston. Allston had phases as a painter of precise genre scenes, a history painter, a follower of Poussin with Italian Landscape (1805, Addison Gallery), and a follower of Michelangelo with Uriel in the Sun (1817, Boston University), and was known for his glazes from midcareer on. This article will focus on historical sources and visual examination of the small, late pictures by the older Allston, a poet and philosopher in his 50s. In these misty, melancholy, visionary images Allston seems at last to be less a mimic of other artists' styles than a synthesizer of his own dreams in both words and glazes. 1 HAZE AND MISTY VEILSALLSTON'S The Spanish Maid like several of his other works, is both a painting (figure 1) and a poem (appendix 1), and the two must be considered in tandem. H.W.L. Dana (1943, 49) noted that the conception of the poem and the picture had been simultaneous in Allston's mind. In Allston's poem, Inez is sitting on an isolated grassy knoll, waiting for her lover Isidor, who has been gone for five months. She is suspended between dreams of his valiant fall and a longing for his safe return. In the painting, there is deep recession of space, although the actual landscape perspective is a bit ambiguous. The entry in the Metropolitan Museum of Art catalog (in press) reads: “Through an extraordinary blend of blue, red, and green, the landscape is now a confusing blur, and one has trouble imagining its original appearance.” The “blur” was probably quite intentional as the poem

The “twenty times” of glazing applications are likely to have contributed to the severe crackle pattern throughout the painting. In order to carry out multiple glazings, Allston often added Japan gold size drier to his medium—a mixture of Kauri gum (a hard resin) and turpentine, boiled oil, litharge, red lead, and manganese dioxide (a strong drying agent often used by sign painters). He also added megilp to his paints—a mixture of mastic, oil, and turpentine that unfortunately darkens with age but has a buttery consistency enjoyable to paint with and maintains a “vernished” look for the oil paint as one is working. Megilp can also cause fissure cracks if used heavily. Earlier landscapes such as Elijah in the Wilderness (1818, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which Allston told Thomas Sully he painted in colors ground in skimmed milk, show more precision and linearity, but Allston later became interested in haze, mystery, blurred outlines, and the effect of light and atmosphere. In Landscape, American Scenery: Time, Afternoon with a Southwest Haze(figure 2), the soft misty effect of the distant trees was created by reddish brown asphaltum glazes with little solid impasto beneath (Jones 1947, 9).

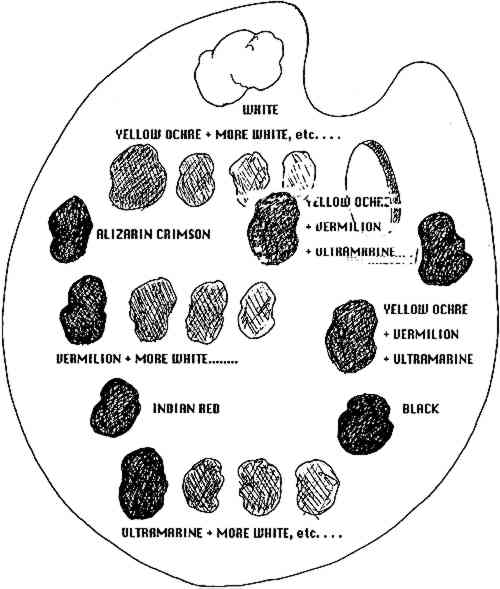

William Page (1845, 201) uses the word “veil” in discussing Allston's techniques in the Broadway Journal. He writes, perhaps with some professional jealousy, about Allston's color, indicating, “I cannot subscribe to his perfection in color, especially in his later works. Many think Titian scarcely finer, if so, I have overrated Titian.” But in discussing light colors passed over darker ones, Page notes that Allston “doubted this could have the look of a white veil,” to which Page replies, “Is not the skin in some degree a veil?” E. P. Richardson (1948, 147) notes that one of Allston's landscapes was “seen through the veil of memory and transposed to another plane by having lived long within the mind.” The esthetic of Allston's veil seems to be not only blur from mists and haze but also technical veils of paint and the gentle blur of the remembrance of things past. The female figure in The Spanish Maid may be based on Allston's memory of his first wife Ann, who died in 1815. The figure is very similar to his Life Study of Ann Channing (ca. 1812–15, Massachusetts Historical Society). 2 ALLSTON'S PALETTE AND COLOR THEORIESWHEN ALLSTON saw the Venetians in Napoleon's Louvre, he commented, “It was the poetry of color which I felt.” Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese “took away all sense of subject” with their “gorgeous concert of colors” (quoted in Dunlap 1918, 2:306). Allston became interested in glazing and was called “The American Titian” by the artists in Rome (Dunlap, 1918, 2:315). But what were the colors of the Titians that Allston saw? He may have seen the Venetian works covered with the discolored brownish “gallery varnish” that seeded the controversies in Paris and London 30 years later. The paintings were surely varnished; Charles Leslie (1860, 22) complained that his first history picture was not allowed in the British Institution's exhibit of 1814 on the grounds that it was not varnished and therefore looked “unfinished.” Leslie also noted. “Allston first directed my attention to the Venetian school, particularly to the works of Paul Veronese, and taught me to see, through the accumulated dirt of the ages, the exquisite charm that lay beneath.” Clearly Allston was aware of discoloring surface layers. Allston's palettes and detailed coloruse recommendations have been extensively documented by Nathaniel Jocelyn as of August 1823 (Morgan 1939, 131–34), by Sully (1965, 32–35) during a visit to Allston in 1835, and by Greenough's lengthy descriptions published by Flagg (1893, 181–201). Greenough's descriptions are undated, but were, according to Flagg, written for R. H. Dana, Sr., as a contribution to his proposed biography of Allston. Following Allston's death in 1843, Greenough cleaned and prepared Belshazzar's Feast (unfinished, Detroit Institute of Arts) for exhibition and wrote articles for Dana and the Boston Post (Greenough 1966, i). It is therefore assumed that his writings quoted by Flagg are from 1844. A reconstruction of the Allston palette as described by Greenough appears as figure 3.

All the palette colors mentioned by Jocelyn are in Greenough's account, and more. Jocelyn lists yellow ochre and its three tints as the only yellow, but Greenough notes that the yellow (yellow ochre, raw sienna, or Naples yellow) was chosen according to the complexion Allston was about to paint. Allston's palette of 1823, however, reflected the entire painting, not just the flesh tones. Elizabeth H. Jones (1947, 4), former conservator of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, observes, “It is striking in its severe limitation on the number of pigments used.” Still it took Allston half an hour to mix and meticulously spread out on his palette each day (Flagg 1893, 242–43). Possibly to cut down on glaring white reflections and distractions, as painting conservators do today, Allston had the walls of his Cambridgeport, Massachusetts painting room tinted Spanish brown (Dana 1943, 168). The general tonalities of Allston's paintings are warm and brown, reflecting what Richardson (1944, 55) calls a “golden” or “brunette” palette. He notes that “Allston created for American painting a warmer and more golden tonality, which is the spiritual ancestor of the warm palette of Inness, Page and Eakins.” With megilp and interlayerings of varnish, the “warm” or “golden” effect would likely increase with age. George Field, the color theorist, visited Allston's painting studio in London in 1815. Field had seen Allston's painting The Sisters (ca. 1816–17, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University), which was painted in the tertiary colors using theories Field was writing about. Allston had arrived at the same theory independently. As Elizabeth Johns (1977, 15) explains, “For both Allston and Field, the significance of the tertiaries was that they alone on the color wheel contained all three primary colors and thus were a physical symbol of the ultimate harmony in the universe.” (For instance, citrine equals green +

Allston's use of tertiaries makes verbal color descriptions difficult and hyphenations mandatory. To describe the colors of The Spanish Maid, one resorts to “a pinky-beige hat,” “dried-blood red velvet,” or a “mustard-green belt.” Richardson's color descriptions of Allston's The Sisters include “puce-colored dress,” “cherry-brown blouse,” and “brownish purple skirt.” In describing Allston's Diana and her Nymphs in the Chase(1805, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University), the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge lists “beautiful purple-crimson mosses” and “grey-blue faintly purplish” rock (Coburn 1944, 25). In comparison to other artists' palettes, Allston preserved a triad symmetry of hue, even as he tinted up quantifiably with white, by basing his triad on what he calls the “crude” three primaries. For flesh, Allston (quoted in Flagg 1893, 185–86) aimed toward what he considered Titian's “luce di dentro” or “internal light” technique, which he compared to a purple silk woven of red and blue threads. The flesh tints are to be mingled lightly “with the brush only,” “twiddling them together instead of grinding them with a knife.” An up-close examination of the face of The Spanish Maid does reveal a Seurat-like complexion composed of colors that blend best to the eye at a slight distance.

The Spanish Maid has greenish brown eyes and distinctively staring black pupils with no highlights. Her eyes do seem to be intently fixed on some “object,” which may be the real or the imagined returning Isidore. Allston represents a sort of bridge between painting and poetry and between technical and symbolic concepts about uses of certain colors or pigments. He ranged from the pedestrian concerns of avoiding Prussian blue (Sully 1965, 32), noting its property of changing color when dry (Jones 1947, 5) to the writing of the “The Paint-King,” a poem in which the heroine (who, we have been told, is beautiful but has a “barren waste” for “her mind”) is actually ground up for pigments (Allston 1850):

∗Here “The Paint-King” duplicates the same “masterly care” Flagg describes Allston's taking each day with the laying out of his palette. Later in the poem, however, the reader learns that the portrait painted by “The Paint-King” is not considered successful, perhaps because, as Allston declared in his “Lectures on Art” (Allston, 1850), mere imitation or reproduction cannot produce great art; the artist's imagination must synthesize borrowed elements. (Also, a mouse has run off with Ellen's pupils.) Fortuitously for technical study, there are many unfinished Allstons through which one can study his solid buildup of dead-colors in black, white, and Indian red and his underpainting with the parallel tints, and compare the actual with the descriptions from Greenough, a comparison that holds up well. 3 ASPHALTUM TONINGS AND “TITIAN'S DIRT”WASHINGTON ALLSTON used toned coatings, which were probably a nightmare for the first 19th-century restoration practitioners who approached his work. His practice was not unusual for his time: William Dunlap (1918, 2:306) describes landscape artist Richard Wilson's dispatching a porter for Indian ink and Spanish licorice, which he then dissolved in water and “washed half the pictures of the annual exhibition in Spring Gardens of the Society of Painters with the glaze considered 'as good as asphaltum.'” Benjamin West commented, “They were all the better for it.” Allston mixed what he called “Titian's dirt,” which was asphaltum, Indian red, and ultramarine plus megilp. One version included Japan size to make it dry faster, and one version did not, so he could work with it longer. Allston (quoted in Flagg 1893, 187) told Greenough, “With this I go over the face, strong in the shadows and lighter in the half-tints; with a dry brush or rag, I wipe off the glazing or weaken it as I wish, and in this way, model up the general form and detail … very much like water-color painting … left moist.” Allston had a great interest in unity and harmony, and it is likely that versions of “Titian's dirt” were used throughout most of his career. The Greenough reference above mentions this technique in connection with Allston's early-in-life trip to Rome, so it is not just a later life phenomenon. William Gerdts (1969, 184) notes that many artists unwisely Because of the presence of darkening megilp, soluble glazing, and the readily removable “Titian's dirt” coatings, the first restorer who cleaned each Allston painting may have changed it significantly. Now, at least six generations of owners later, finding an Allston painting that still has his original toning is probably unlikely. Allston himself “in 1839, on seeing his heavily glazed Diana in the Chase, after a lapse of twenty-four years, disclaimed real authorship of the work, saying that the picture cleaner had totally destroyed his conception” (Johns 1979, 70 n.79). However, conservator Mark Aronson was recently fortunate enough to study and treat Allston's Taming of the Shrew (1809, Philadelphia Museum of Art), which appeared to be an exception. After study of a cross-section of red drapery with fluorescent staining, he felt that the rough interface between the original varnish (which had an interactive zone with the original paint still present) and the later varnish suggested that varnish reduction had been carried out mechanically so there was little evidence of change of visual impact through solvent cleaning (Aronson, letter to author, December 23, 1988). The Spanish Maid was most recently cleaned in 1980 by conservator Dianne Dwyer, while the author was a visiting scholar in the Paintings Conservation Studio at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Aware of Allston's glazing techniques, Dwyer reduced the varnish film rather than attempting to remove totally the discoloring varnishes applied since Allston's time. Art historians are not often known for their close observation of the mechanics of picture cleaning; it is unusual and therefore telling that there are at least two overt references to problems caused by cleaning in the current art historical literature on Allston. Elizabeth Johns (1979, 70) comments about the Dead Man Revived (1811–14, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts): “Although nineteenth-century restoration removed many of Allston's glazing layers, one can still see evidence of his use of pure colors in glazes of red over blue, blue over gold, and blue over red, which pulled his tonalities into a unity based on the primary colors.” Chad Mandeles (1980, 145 n.9) writes regarding The Evening Hymn (1835, Montclair Art Museum) that he suspects “a shadow appeared over the woman's face which was removed, perhaps through overambitious cleaning, at some date prior to 1961.” When he died, with Belshazzar's Feast still in progress on the easel, Allston was much respected by his peers for his gentle demeanor, “unearthly air” (Harris 1966, 237), and constant introspection. The walls of his studio were covered with his aphorisms about excellence, reverence, and humility and the importance of avoiding love of gain, envy, and pursuit of popularity. He is no longer particularly popular, and his poems have fallen into obscurity, but his later paintings and his writings, when discovered, offer misty visions of early 19th-century art theory and cautionary thoughts for art conservators. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI WOULD like to relay special thanks to Irene Konefal at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Ruth Barach Cox formerly with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Mark Aronson, formerly a Fellow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for their help during research on the techniques of Allston, and to Professor Wayne Craven of the University of Delaware for his bibliographic guidance and expertise on Grand Manner painting in American art. APPENDIX1 APPENDIX 11.1 THE SPANISH MAID

REFERENCESAllston, Washington. 1967. Lectures on art and poems. [1850] Introduction by Nathalia Wright. Gainsville: Scholars' Facsimilies and Reprints. Coburn, Kathleen. 1944.Notes on Washington Allston from the unpublished notebooks of S.T. Coleridge. Gazette des Beaux-Arts 25, Ser.6:249–52. Dana, H.W.L.1943. Allston at Harvard 1796–1800; Allston at Cambridgeport 1830–43, Cambridge Historical Society Publications29:13–67. Dunlap, William. 1918. A history of the rise and progress of the arts of design in the United States. Vol. 2. Boston: C. E.Goodspeed. Flagg, Jared B.1893. The life and letters of Washington Allston. London: Richard Bentley and Son. Gerdts, William H.1969. Washington Allston and the German romantic classicists in Rome. Art Quarterly32:166–96. Greenough, Henry. 1966. Washington, Allston: American artist as a painter. [1892] Ed.H. DouglasCurry. Bath, England: Wyatt and Reynolds. Harris, Neil. 1966. Artist in American Society. New York: George Braziller. Johns, Elizabeth. 1977. Washington Allston: Method, imagination and reality. Winterthur Portfolio12:1–18. Johns, Elizabeth. 1979. Washington Allston's Dead Man Revived. Art Bulletin61 (March):78–99. Jones, Elizabeth H.1947. Washington Allston's painting technique and his place in the coloristic tradition. Unpublished typescript. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. Leslie, Charles R.1860. Autobiographical recollections. Ed.TomTaylor. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. Mandeles, Chad. 1980. Washington Allston's The Evening Hymn. Arts Magazine54(December-January):142–145. Morgan, John Hill. 1939. Nathaniel Jocelyn's record of the palettes of Gilbert Stuart and Washington Allston. New York: Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin23(October):131–34. Page, William. 1845. The art and the use of color in imitation in painting. no 6: Reynolds, Alston [sic], Stuart. Broadway Journal (March 29):201–2. Richardson, E. P.1944. Allston and the development of romantic color. Art Quarterly7(Winter):33–57. Richardson, E. P.1948. Washington Allston: A study of the romantic artist in America. New York: Thomas Y.Crowell.

Sully, Thomas. 1965. Hints to young painters. [1873] New York: Reinhold. AUTHOR INFORMATIONJOYCE HILL STONER is the Director of the Art Conservation Program sponsored jointly by the University of Delaware and the Winterthur Museum and for which she has taught Painting Conservation and the History of Conservation for 14 years. She was also the Managing Editor of Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts for 17 years. She received her Master's degree and her conservation training at the Conservation Center of New York University. She has been a visiting scholar in the painting conservation departments of the Metropolitan Museum and the J. Paul Getty Museum. She has recently completed the course work for a Ph.D. in Art History and plans to write her dissertation on Whistler. She is now consulting on the treatment of Whistler's Peacock Room at the Freer Gallery of Art. Address: Art Conservation Program, University of Delaware, 303 Old College, Newark, Delaware 19716.

Section Index Section Index |