PAINTINGS ON A PHOTOGRAPHIC BASE

Mervyn Ruggles

5 ARTIST AND PHOTOGRAPHER PARTNERSHIPS

AS THE TECHNICAL ASPECTS IMPROVED, especially in the making of portraits, photographers hired professional artists11 to apply their talents in the photographic studio. Their patrons were eager to have portraits resemble painted likeness. By the 1860s, portraits in color became fashionable. Photo enlargements were produced, pasted on canvas and mounted on an artist's stretcher, then, using oil colors, watercolors or chalks,12 the artist would convert them into paintings. Later, these would be varnished and fitted into ornamented gilt frames. Sometimes, the negative was projected onto paper in the dark room while the artist sketched in the details with a graphite pencil or charcoal, then painted over to produce the oil painting. These portraits were popular because they were less costly than free-hand paintings which required long sittings. They also had the detail and realism that often were not captured in conventional oil portraits. Here are some comments by a well-known artist, William Sawyer (1820–1889), who had a business at 113 St. Peter Street, Montreal, as reported in the Montreal Gazette newspaper13 of January 24, 1872:

“…Mr. Sawyer desires it to be particularly understood that his portraits are veritable oil paintings painted by hand directly on the canvas and not a photograph of the person faintly taken on canvas and then painted thinly over as is so frequently done by inferior artists and palmed off as genuine oil portraits. At the same time, Mr. Sawyer does not ignore photography as a valuable assistant but will not tolerate the questionable use of it as a foundation for an oil painting. The painting of the ancient masters have lasted from century to century, because when they were executed, paint was used with no stint and with no more oil than necessary to mix the colors. In the case of the semi-photograph pictures, the paint is thinly laid on with a great deal of oil and it is a certain consequence in the course of time that the picture suffers by deterioration and finally becomes worthless at an early date. In the studio there are several paintings and numerous beautifully finished coloured photographs of leading residents in the city. The photograph department is in the able charge of Mr. E.R. Turner, a photographer well known in the city. Under his charge, the fine work from the department in the shape of card and cabinet photographs, plain or beautifully colored, are liberally exhibited for the inspection of the visitor.”

In spite of William Sawyer's statement in the first part of this interview, he was known to have painted portraits on a photographic base for his clients.

A young man in his twenties who had some art training and had learned to take daguerreotypes, William Notman (1826–1891),14 came to Montreal from Paisley, Scotland. He set up a photographic studio in 1856 at 17 Bleury Street, just at a time when photography was in great demand and business was booming, the trans-Canada railway was under construction and Canada's financial and main trade centre was in Montreal. Notman's establishment was so successful that branch studios were set up in Ottawa in 1868, in Halifax in 1869, Toronto in 1872, and in Boston, Albany, and other centres. Because of the high artistic quality of his portraits and the reasonable prices, $1.50 for an 8″ � 10″ black and white,15 Notman prospered and his studio became popular among all classes of Montreal society. He also did a brisk business in enlargements colored in oil or watercolor which were mounted in the finest ornamented gold leaf frames. The fee for one of these in 1865 would cost $100 or more (Figs. 3, 4).

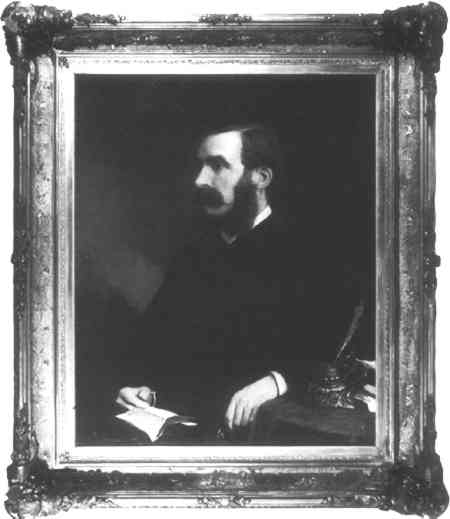

Fig. 3.

Painted photograph of Thomas Morland, 1870, oil on canvas, 35″ � 29″ (85.0 � 73.7 cm), enlargement directly on canvas from a cabinet photograph by William Notman (1826–1891), painted by Edward Sharpe (active 1860–1870). The frame was made in the Notman framing department. (Photograph courtesy of the Notman photographic archives.)

|

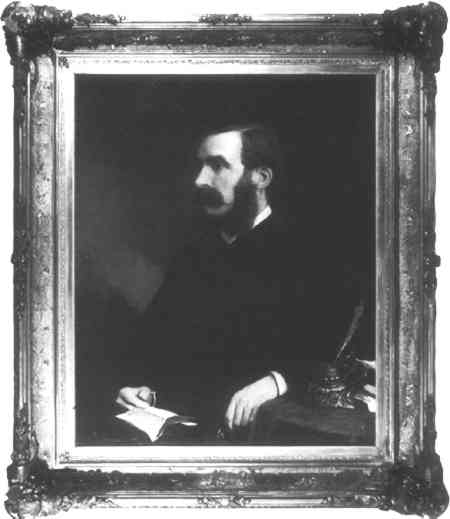

Fig. 4.

Cabinet photograph of Thomas Morland, 1870, 5″ � 3�″ (12.7 � 9.0 cm), from which an enlargement was made directly on artist's canvas. (Photograph courtesy of the Notman photographic archives.)

|

Notman employed a number of professional16 artists to produce painted photographs: John Henry Sandham (1842–1910),17 George Horne Russell (1861–1933), Otto Jacobi (1812–1901),18 Edward Sharpe (active 1860–70), and Frederick Arthur Verner (1836–1928). One of the most talented in this group was John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898), who was appointed head of Notman's department in 1860 at a monthly salary of $125.00 (according to Notman's wages book). An example of the excellent quality of his work is the portrait of young Bryce Allan (Fig. 5), a 20″ � 27″ enlargement from a carte-de-visite done in 1866 (Fig. 6). For the painted photographs from the carte-de-visite size (3�″ � 2�″) or cabinet photograph (5″ � 3�″), negatives were projected on sensitized paper, processed in the usual way, then pasted to canvas mounted on a stretcher frame or cardboard support. After the artist had completed the painting, it was put into an ornamented gilt frame. William Notman had set up his own framing department for this purpose. In fact, at the peak of his career, he had a staff of 57 people.19

|