PAINTINGS ON A PHOTOGRAPHIC BASEMervyn Ruggles

ABSTRACT—This paper reviews the history of the oil portrait painted over a photographic base, popular in the second half of the 19th century. Problems in the examination and conservation of these portraits are described. 1 INTRODUCTIONSHORTLY AFTER THE INVENTION of photography, artists in the United States and Canada began to explore in several ways the possibilities of the photographic image for their own use. Towards the latter part of the 19th century, some artists advertised themselves as “artist-photographers,” reflecting the aura of prestige of photography, which seemed to attract the notice of the general public. As the technical aspects improved, especially in the making of photographs, photographers who did not have artistic talents hired artists to work for them in the photo studio. Their patrons were eager to have photographs resemble painted likenesses. Prominent artists participated actively in producing painted photographs. Photographers prepared enlargements which were then painted over in oils by staff artists. By the 1860s, colored portraits became fashionable and techniques improved rapidly. Methods were found to photo-sensitize the canvas surface on which the enlarged portrait was projected and fixed. The artist then applied paint directly on the image. The finished art work would later be varnished and placed in an ornamented gilt frame. Frequently, these paintings are not easily recognized as being based directly on a photo image. The influence of photography, from the time of its invention, on painting has been a powerful one and continues to the present day. Likewise, it cannot be denied that painting has had a profound effect on photography. Moreover, it is a rather significant fact that the first practical and popular method of taking photographs was invented by a professional artist, Joseph Jacques Mand� Daguerre (1787–1851), thereby starting that great on-going debate as to whether photography is an art or a science. 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDTHE INVENTION OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC camera was a development from the portable camera obscura. The experiments in producing images on a flat surface by Wedgwood, Davy, Ni�pce, Talbot and others are well documented. However, the first announcement of the daguerreotype was made on the inventor's behalf by F.D. Arago,1 a distinguished physicist and astronomer, at a meeting of the Acad�mie des Sciences in Paris on January 7, 1839. From then on the daguerreotype was launched like a rocket and knowledge of the process spread rapidly to many parts of the world within the next year. A number of phases in the life of Daguerre had led up to this event. At the age of 27, Daguerre had a painting of his accepted for the Paris Salon of 1814. He subsequently became interested in painting dioramas, exhibiting his first one, 71 feet long by 15 feet high, in Paris in 1822 and a second diorama in London by 1824. As is well Daguerre's mirror-like images, devised partly by accident, could not have come at a more propitious moment. Daguerreotypes, plain, tinted and in stereo, were exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and przes given for the best entries. In this competition, Matthew Brady, who later became the celebrated American Civil War photographer, was awarded a medal for one of his daguerreotypes. Photographic studios sprang up everywhere. The public could acquire portraits of themselves and members of their families cheaply. People now accustomed to miniatures were delighted with the great detail and the realism that the daguerreotype gave them without great expense. Then, in 1851, Frederick Scott Archer published his invention of the collodion2 on glass process, bringing the popularity of the daguerreotype to an end by 1860. Many professional artists advertised themselves as artist-photographers in order to get a share of the prosperity of this new wave. Artists like Eug�ne Delacroix, Edgar Degas, Gustave Courbet, Edvard Munch and many others used photographs to compose paintings or to make direct copies; just as portraits of Abraham Lincoln were painted directly from photos as models, by Thomas Sully in 1864 and George Henry Story in 1866.3 In the early days of daguerreotype portraiture, Queen Victoria asked Alfred Chalon (1780–1860), the fashionable French miniature painter, whether he was not afraid that photography would ruin his profession. “Ah, non, Madam,” he replied, “photography cannot flatter!”4 3 SCOPE OF THIS STUDYIN AN ATTEMPT TO SATISFY increasingly exacting demands on their clients, photographers added touches of color to cheeks, lips, backgrounds and gold paint to jewelry5 endeavouring to inject more realism to their portraits. In order to enhance landscape photographs, frequently a sky from one photo, trees from another, and figures from a third would be combined like a collage and re-photographed.6 To many artists, the daguerreotype or photograph was looked upon merely as another tool, much as the camera obscura7 had been used as a guide in perspective and for positioning various details in paintings for centuries. In the beginning of the 19th century, the camera lucida,8 an instrument with a prism viewing device, had become popular with artists as an aid in drawing and making sketches. Basil Hall (1788–1844), after a tour in North America in 1827–28, published in England, in 1830, an album entitled, “Forty Etchings from Sketches made with a Camera Lucida,” stating “ … the camera lucida is a valuable instrument, it enables a person to make correct outlines of scenes.”9 However, copying, tinting, superimposed collages or the use of the photo as a tool are not the concern of the present study. It is the aim of this paper to pursue particularly the development of the painted image, where the photograph itself becomes the schema, the sinopia, the underdrawing of a painting executed by a professional artist. 4 THE CARTE-DE-VISTEIN 1854, ANDR� DISD�RI (1819–90),10 who had a studio at 8 Boulevard des Italiens in Paris, patented the technique of producing the carte-de-viste photograph. Disd�ri had the idea of replacing the ordinary business card with a miniature portrait. His conception of these 3�″ � 2�″ photographs became extremely popular everywhere. Cartes-de-viste were produced with portraits of royalty, notable people, views of well known places. Also, miniature portraits were made on white card or heavy paper for sale to miniature artists who then painted over them to resemble miniatures on ivory (Figs. 1, 2). Subsequently Disd�ri was appointed court photographer by Napoleon III in 1861.

5 ARTIST AND PHOTOGRAPHER PARTNERSHIPSAS THE TECHNICAL ASPECTS IMPROVED, especially in the making of portraits, photographers hired professional artists11 to apply their talents in the photographic studio. Their patrons were eager to have portraits resemble painted likeness. By the 1860s, portraits in color became fashionable. Photo enlargements were produced, pasted on canvas and mounted on an artist's stretcher, then, using oil colors, watercolors or chalks,12 the artist would convert them into paintings. Later, these would be varnished In spite of William Sawyer's statement in the first part of this interview, he was known to have painted portraits on a photographic base for his clients. A young man in his twenties who had some art training and had learned to take daguerreotypes, William Notman (1826–1891),14 came to Montreal from Paisley, Scotland. He set up a photographic studio in 1856 at 17 Bleury Street, just at a time when photography was in great demand and business was booming, the trans-Canada railway was under construction and Canada's financial and main trade centre was in Montreal. Notman's establishment was so successful that branch studios were set up in Ottawa in 1868, in Halifax in 1869, Toronto in 1872, and in Boston, Albany, and other centres. Because of the high artistic quality of his portraits and the reasonable prices, $1.50 for an 8″ � 10″ black and white,15 Notman prospered and his studio became popular among all classes of Montreal society. He also did a brisk business in enlargements colored in oil or watercolor which were mounted in the finest ornamented gold leaf frames. The fee for one of these in 1865 would cost $100 or more (Figs. 3, 4).

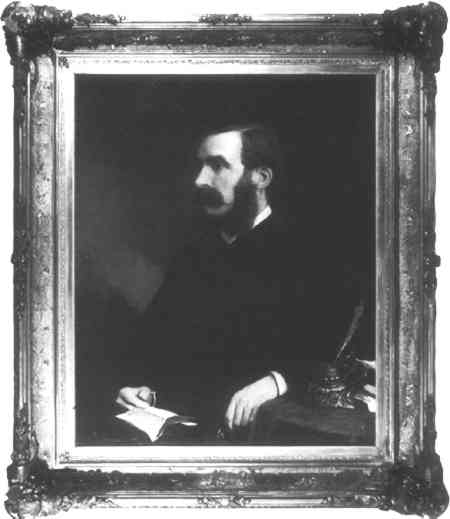

Notman employed a number of professional16 artists to produce painted photographs: John Henry Sandham (1842–1910),17 George Horne Russell (1861–1933), Otto Jacobi (1812–1901),18 Edward Sharpe (active 1860–70), and Frederick Arthur Verner (1836–1928). One of the most talented in this group was John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898), who was appointed head of Notman's department in 1860 at a monthly salary of $125.00 (according to Notman's wages book). An example of the excellent quality of his work is the portrait of young Bryce Allan (Fig. 5), a 20″ � 27″ enlargement from a carte-de-visite done in 1866 (Fig. 6). For the painted photographs from the carte-de-visite size (3�″ � 2�″) or cabinet photograph (5″ � 3�″), negatives were projected on

6 METHODS OF SENSITIZING CANVASIN THEPhiladelphia Photographer magazine of June 1868, Isaac Rehn's patent20 for sensitizing a canvas surface21, 22, 23 was described under the title of “Solar Printing on Canvas.” The process consisted of coating the canvas with a mixture of zinc white, egg albumen, ammonium chloride and silver nitrate. This solution was brushed over the canvas, which was exposed under the negative in the enlarger. The image was fixed with sodium thiosulfate in the normal manner. Albert Moore24 had a photography business at 710 Arch Street, Philadelphia, advertising the fact that he would print photos on paper or canvas from negatives supplied by clients. For a canvas 40″ � 30″ the price was $5.00, cost of canvas and stretcher extra (Fig. 7).

7 EXAMINATION AND CONSERVATIONQUITE OFTEN, THESE PAINTED portraits are difficult to recognize because the photo image cannot be easily detected, being hidden by the paint film. Careful examination under magnification is required, especially in areas of the face, in details of the eyes, nose, mouth and the hands. The subtle gradations produced by the grains of silver in the emulsion or collodion or albumen of these regions allowed the artist to apply only a thin glaze of color. Otherwise the modelling would be lost. Other sections, such as costume, details of the clothing and background permitted the artist to use thick paint and the opportunity to improvise the colour arrangement. The staff artist would need to be present in the studio at the time that the sitter was having the photo taken in order to observe the coloring of his client's features and clothing for an accurate likeness, or details would be noted for the artist's information later if he were not present. The attempts to confirm the presence of a photo image under a paint layer by means of radiography, Infra-red Vidcon or x-ray energy spectrometry (EDX) have not been successful to date; usually the overlying pigment tends to screen out the silver grains. However, presence of a paper support lying over a canvas should immediately alert the conservator to make a careful search along the marginal regions for some trace of a silver image. Examination under the binocular microscope so far seems to be the best method for seeking the presence of silver grains. Any surface accretion or discoloration should be treated with extreme caution. Solvent tests should be made first with absorbent cotton on small applicator sticks slightly moistened with diluted mild detergent at a place which lies under the frame rabbet. All that may be possible would be to remove surface soil only, because any coatings usually are extremely fragile, being a combination of a resin and pigment in the form of a glaze overlying a film of water-soluble gum arabic. In some instances, a coating of megilp, a mixture of dammar resin and boiled linseed oil, may be present. Megilp is known to become discolored in a short period of time and turn brittle, causing a network of craquelure promoting seepage by capillary action to lower layers of any solvent that may be introduced on the surface. In the case of watercolor over a silver image, the problem is reduced as the work is usually protected by glass. Should foxing or water stains be present, conservation treatment would proceed in the manner for works of art on paper. 8 SUMMARYOIL PAINTINGS OR WATERCOLORS, once they are detected as being on a photographic base, are composed of a delicate complex structure with the combined characteristics, in many instance, of a textile (the canvas support), paper, photo image, oil paint layer, and a varnish coating. These portraits are now becoming not only collector's items, but also important historical documents as well as works of art and are acquiring considerable heritage value. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTHE AUTHOR WISHES TO EXPRESS his special thanks for their valuable assistance to Stanley G. Triggs, Curator of the Notman Photographic Archives of the McCord Museum, McGill University, Montreal, and his assistant, Norah Hague; Ann Thomas, Assistant Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Canada; Maija Vilcins, Reference Librarian at the National Gallery of Canada; the National Library of Canada, and the Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa. PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTMAN PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES, Montreal; Donald M. Shaw, Summerstown, Ontario; Claude Gougeon, Peterborough, Ontario; National Gallery of Canada; Public Archives of Canada. REFERENCESGernsheim, Helmut and Alison, “L.J.M. Daguerre, The World's First Photographer and Inventor of the Daguerreotype” (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1956), p. 79. Archer, Frederick, S., “The Collodion Process on Glass” (London: Printed for the author, 1854). Coke, VanDeren, “The Painter and the Photograph from Delacroix to Warhol” (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1971), pp. 232–239. Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison, “The History of Photography, 1685–1914” (New York, St. Louis and San Francisco: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969), p. 118. “In the early days of daguerrotype portraiture, Queen Victoria asked the fashionable miniature painter Alfred Chalon whether he were not afraid that photography would ruin his profession, 'Ah, non, Madame', he replied in a mixture of French and English, 'photographie can't flat�re'.” Originally published in “The Women at Home”, London, vol. VIII, 1897, p. 812. Ayres, George, B.How to Paint Photographs in Water Colors (Philadelphia: Benerman & Wilson, 1869). Sobieszek, Robert, A., “A Note on Early Photomontage Images,” Image, Vol. 15, No. 4, December 1972, International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House Inc., Rochester, N.Y., pp. 19–24. The camera obscura was invented by Erasmus Reinhold of Wittenberg in 1540, improved by Porta in 1558 and made into a tranportable unit by Hook in 1679. Gettens, R.J., and Stout, G.L.S, Painting Materials. A Short Encyclopedia (New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1966), p. 284. The camera lucida was invented by Wollaston in 1807. Gettens and Stout, op.cit., p. 284.

Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison, “The History of Photography, 1685–1914”, op.cit., pp. 26 and 51. The camera lucida consists of a glass prism eyepiece mounted on a tripod on a drawing board permitting the simultaneous view of a hand-manipulated pencil to draw the outline of a scene. StaffFrankThe Picture Postcard & Its Origins (London:Butterworth Press, 1966), 42–43. Boulet, Roger, Frederic Marlett Bell-Smith (1846–1923), Exhibition cataloque, Art Gallery of GreaterVictoria, B.C. (Victoria, B.C.: Moriss Printing Co. Ltd., 1977), pp. 16–17. Ayres, George, B., How to Paint Photographs in Water Colors and in Oil (Philadelphia:Benerman & Wilson, 1871), pp. 21–25. Anonymous. “Mr. Sawyer's Art and Photograph Studio,” The Gazette, Montreal, Vol. CI, No. 24, January 24, 1972, p. 2. Harper, J.R. and Triggs, S.editors, Portrait of a Period, Notman Photographs 1856–1915 (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1967), unpaginated. Notes supplied to the author by Stanly G. Triggs, Curator of the Notman Photographic Archives, McCord Museum, McGill University, Montreal, October 27, 1982. Thomas, Ann, Fact and Fiction: Canadian Painting and Photography 1860–1900, McCord Museum, Montreal: Plow & Watters Ltd., 1979), pp. 33–44. Harper, J. Russell, Early Painters and Engravers in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970, pp. 276–280. Hubbard, R.H., Catalogue of Paintings and Sculpture, Vol. III, Canadian School (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1960), pp. 272–273. Triggs, S.G., loc.cit. Rehn, Isaac, “Solar Printing on Canvas,” The Philadelphia Photographer, Vol. V, No. 54, June 1868, pp. 190–191. Anonymous, “Photographs on Canvas,” The English Mechanic, Vol. I, No. 3, April 14, 1865, p. 27. Lucas, J.T., “Photography on Canvas,” Photographic News, Vol. VII, No. 22, January 9, 1863, London, p. 23. Towler, John, M.D., “To Prepare Canvas for the Reception of a Photograph,” The Philadelphia Photographer, Vol. V, No. 54, June 1868, p. 194. Moore, Albert, “Solar Printing,” an advertisement, Ayers, G.B., “How to Paint Photographs in Water Colors” (Philadelphia: Benerman and Wilson, 1869), p. 132.

Section Index Section Index |