YELLOWING AND BLEACHING OF PAINT FILMSHenry W. Levison

1 PREPARATION OF TEST SPECIMENSTHE TESTING PROCEDURE WAS developed from previous experience. For the short term tests it is easiest to use the lacquer-covered paper opacity charts. For the long-term exposures, however, the lacquer coating on these charts significantly discolors irreversibly, confusing the results. Therefore, white art posterboard coated with a medium oil length soya alkyd white was used for the longer tests. The formulation of the white paint is as follows: Table 1 Composition of White Ground Paint for Test Panels The ground coat paint was thinned with mineral spirits for flow coating or for spraying the full sheet of posterboard on the highly finished side. Two ground coats were applied to insure complete opacity. After aging a month or more, the sheets were cut into 3″ � 6″ panels for the application of the test paints. With the oil mediums, the specimens were made by mixing equal weights of the oil in the standard mixing white paint (Table 3) relative to the non-volatile in the painting medium. With the acrylic emulsion mediums one part of the medium was mixed by weight with two parts of a proprietary acrylic emulsion titanium white paint. Table 3 Standard Mixing White Oil Paint In order to obtain the mixing weights of the oil painting mediums it was necessary to determine the non-volatile content.8 The non-volatile content of the oil painting mediums used in this test is given in Table 2. Table 2 Percentage Non-Volatile Content of Oil Painting Mediums Tested Zinc oxide was present in the oil mixing white to make certain the safflower oil dried normally and to insure retention of whiteness. The 100% non-volatile mediums were thinned with mineral spirits to 50% non-volatile to produce draw-downs comparable in thickness with mediums containing a thinner. No. 16, with its very low non-volatile of 6.3%, requires 3.56 times as much medium as the standard mixing white paint and not only is difficult to draw down because of the preponderance of thinner, but produces a film thickness of 44% of a non-volatile paint draw-down. All the other white oil paint-mediums mixtures produce a film of 70% thickness or more. The test film produced by No. 16, consequently, is not comparable with the test films of the other mediums. In the test series (Table 4) Nos. 1 through 20 are mixtures of painting mediums with the standard mixing oil white (Table 3) at equal weights of oil in the white to the non-volatiles in the medium (except No. 16 as noted). The acrylic mediums, Nos. 23, 24 and 25, were mixed one part by weight to two parts of LIQUITEX Acrylic Titanium White. Nos. 26 through 32 were tested directly as received. Table 4 Mediums and Paints Tested The specimens to be tested were drawn down with a two inch wide applicator having a 0.0025 inch clearance on the panels previously coated with two coats of white ground paint. The drawn-down test panels were aged six weeks in good light near a window. The initial Yellowness Index (Y.I.) was then measured. The Y.I. calculated as follows, was determined from the tristimulus Values X,Y,Z (CIE 931) measured with a Kollmorgen D-1 large sphere Model Color-Eye� colorimeter. Yellowness indices below 4 were not readily detectable visually.

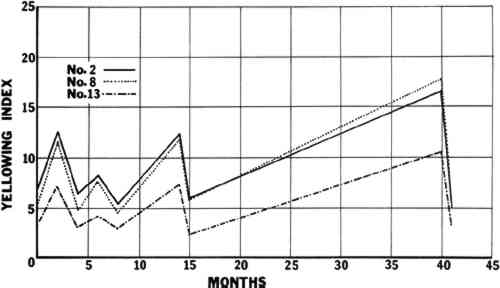

After the initial Y.I. reading the panel was placed in the dark. After removing from the dark, the Y.I. was again determined and the panel exposed to the light. After this bleaching period the Y.I. was again measured and the panel again placed in the dark. The specimens were subjected to four cycles of dark followed by light. For the dark period the panels were stacked, the top and bottom covered with white posterboard the same size, and the assembly held together with rubber bands. The stacked panels were thus stored on a laboratory shelf at ambient temperatures of The first three exposures to the light (periods of bleaching) were obtained by hanging the panels vertically at right angles to a window, facing east, in a position where the sun did not strike the specimens. For the latter two-thirds of the day the sun did not even strike the glass. The level of diffuse illumination on the specimens varied from 10 to 100 footcandles. The panels were exposed in this manner for 60 days after each of the first two dark cycles of 60 days each, then for 30 days after the 180-day dark cycle. The fourth period of light exposure occurred after a location move. In this case, the panels were hung facing a north window, 36 inches away. This was at a time of the year when the sun never directly struck the window; nonetheless, the northern exposure produced an illumination level of from 200 to 300 footcandles. The period of exposure to light here was only 30 days. Rakoff, Thomas and Gast found no difference in the results of exposure facing south and north. Tahk found fluorescent lamplight effective in both the visible and ultraviolet range.11 Table 5 gives the measured yellowness indices, Y.I. through four cycles, following each period of storage in the dark and following each bleaching in the light. See also Figure 1. No perceptible yellowness was seen in any of the acrylic specimens. Table 5 Yellowness Indices After Dark and Light Exposures

|