THE REMOVAL AND CONSERVATION TREATMENT OF A SCENIC WALLPAPER, PAYSAGE � CHASSES, FROM THE MARTIN VAN BUREN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITEPatricia Hamm, & James Hamm

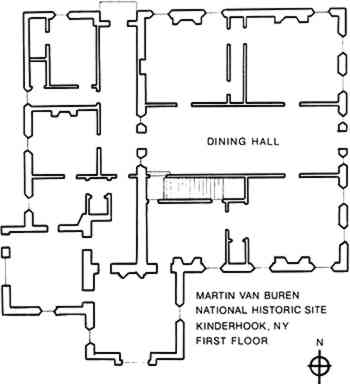

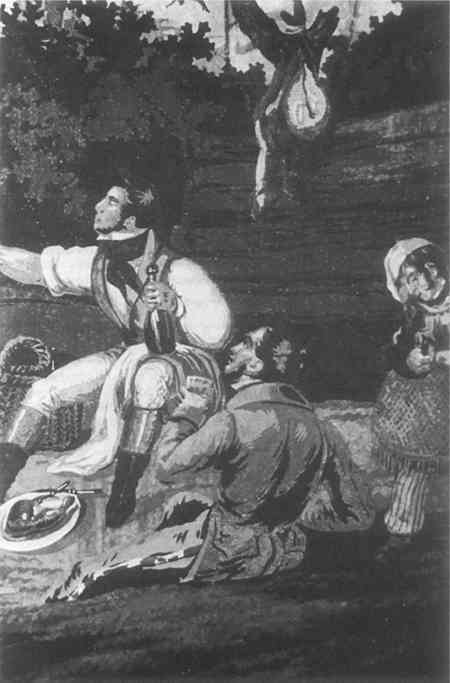

ABSTRACT—Paysage � Chasses, a large scenic wallpaper printed first in 1831 by Jean Zuber et Cie in France, had been purchased by Martin Van Buren during his presidency and survives as one of his few remaining possessions. A summary of the first survey of condition is presented with the reasons why a removal and reinstallation treatment was decided upon. The treatment steps are outlined and recommendations for a more stabilized environment in the future are made based on data collected for one year from a recording hygrothermograph. 1 INTRODUCTIONIN JUNE OF 1977 as we drove up the curved driveway toward the Federal-style house known as “Lindenwald” in Kinderhook, N.Y., we noticed that the National Park Service had already begun its renovations. The front porch had been removed, and uniformed Park Service personnel were all about. The home of the eighth President of the United States, Martin Van Buren, “Lindenwald” had been recently purchased by the National Park Service, and plans were underway for an opening in the spring of 1982, a date that seemed in the distant future. The Curator had requested a survey of the scenic wallpaper in the dining hall. As we were to learn later, this wallpaper and a Brussels carpet from the same room were some of the few remaining possessions known to have been in fact placed there by Martin Van Buren. 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE WALLPAPERTHEPaysage � Chasses scenic wallpaper, printed by Jean Zuber in the 1830's in what is now Alsace-Lorraine, was hung during the redecoration period (1839–41) in the dining hall of “Lindenwald.” It was printed from approximately 1250 woodblocks in 142 colors, and takes its place among the fine scenic wallpapers which were produced in France at that time.1 This example of wallpaper reflects one of the remarkable technical achievements for which the Zuber factory was noted, namely the color-blended effect known as ombr� or iris�.2 The 32 panels necessary to complete the four hunting scenes are repeated 1� times, giving 45 panels on the north and south walls (each panel measuring eight feet long and 18� inches wide). The paper support for the scenics is an early example of the wove, continuous roll type of paper. The decorative dado, printed by Jacquemart and Bernard,3 which was placed below the scenics on the wall was printed on sheets approximately 17″ � 21″. They are of laid, hand-made sheets of paper which had been adhered together before printing the repeating ballustrade pattern. In order to present an account of the wallpaper after “Lindenwald” had passed through the hands of ten owners in 140 years, the authors will describe the scenic wallpaper at the time of their first survey. 3 FIRST SURVEYTHE IMMEDIATELY previous owner, who had used the house as an antique shop, had many of the shop's possessions still piled in the first floor rooms, especially the large dining room. Tapestries were hanging on several sections of the wallpaper along with a large array of pictures. There was little light in the room except from the two small windows on the east wall (Fig. 1). The paper support of the wallpaper panels hanging closest to these windows could be seen through the losses of media to have turned brown. The sky of the wallpaper appeared a glossy, dark green rather than the anticipated matte, pale blue because of a heavy, irregular surface varnish which had darkened considerably. Mold staining appeared through the wallpaper but was especially noticeable in the sky.

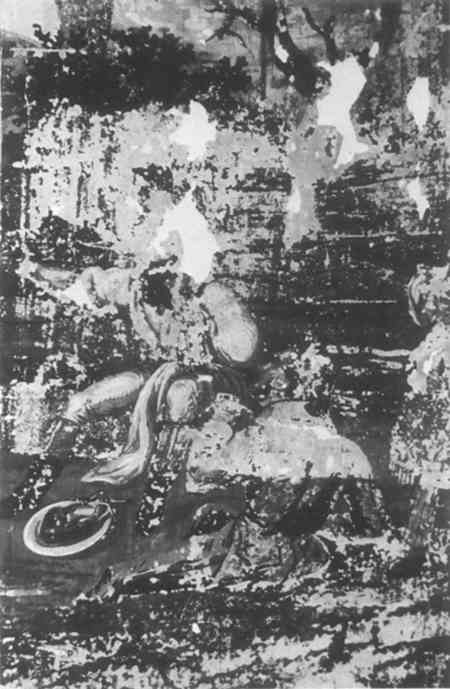

Water damage could be seen in conjunction with a steam radiator as well as from leaks in the roof. There also seemed to be a kind of mottled water-stain appearing in wide expanses throughout the wallpaper. Numerous tears were present, some corresponding to cracks in the walls. Through the many tears one could observe that part of the rough plaster support was crumbling while other smoother areas had been painted dark blue. Hints of painted decorations were noticeable through the dark blue painted areas. Through the tears one could also see that a liner of wallpaper had been placed irregularly throughout the room. Detachment was a serious problem with perhaps only 50% of the wallpaper remaining securely attached to the wall (Fig. 2).

It appeared from certain tears and mends made during the hanging that the wallpaper was either difficult to handle or hung by inexperienced hangers. Its obvious water-solubility had given the hangers further problems. However, it was finally hung with overlapping edges using a strong flour paste. Insects, mostly silverfish living under the moldings and in the cracks in the walls, caused substantial, characteristic losses, while accretions were limited to the lighter printed areas. The manufacturing trait of placing heavy layers of media upon extremely granular ground layers led to the characteristic cracking, cupping, cleaving, and loss of paint found in many French wallpapers (Figs. 3, 4). This fragile attachment meant that merely touching the surface of the wallpaper would send flakes of paint popping off the support. It appeared that certain green copper pigments were creating a severe embrittlement and darkening of the paper support. These weakened areas were sites for concentrated complex tears.

The following observations made that day led us to recommend that the wallpaper should be removed from the wall for its proper treatment.

At an early symposium on the Martin Van Buren wallpaper held in April 1978, a panel of conservators, architectural analysts and curatorial staff concurred with our recommendations for a removal and reinstallation type of treatment.4 The wall area covered originally by the wallpaper was approximately 815 square feet. With the passage of time, more alterations occurring in the dining hall, and by the time of our survey 680 square feet of scenic and dado wallpaper was left to be considered. With the contract negotiations over, conservation treatment began in the fall of 1978. 4 DISCUSSION OF TREATMENT4.1 DocumentationTHE WALLPAPER WAS photographed with 35mm black-and-white negative film and Ektachrome color transparencies. Each wallpaper panel was divided into three frames. The dado was also divided into separate frames. Each photograph included a number code and color or gray scales. The black-and-white negatives were processed archivally and stored in acid-free folders after being printed on resin-coated paper. The color slides were labeled and presented in clear plastic sleeves in a folder. All photographs were keyed to a diagram detailing their placement. Individual examination report sheets were written on each panel and dado, pointing out tears, losses, stains, etc. A survey report was written on the entire collection of wallpaper, listing dimensions, types of paper, media, binders, etc. 4.2 PrototypeBEFORE BEGINNING the treatment on the entire 45 panels, a prototype was selected—the 5� panels in the southeast corner. The treatment of these panels was carried through to the point of reattachment. When it was complete, it was reviewed. It was at that time that the remaining treatment of 600 square feet was begun. 4.3 Treatment Steps

4.4 RemountingREATTACHING to the wall will be done as soon as the restoration of the historic

5 FUTURE STABILITYTHE STABILITY OF the wallpaper in the future is, of course, of interest to the authors. For that reason we have undertaken to survey the environment into which it will be hung and make recommendations. Two factors stand out in our considerations:

Based on studying one year's worth of data from a recording hygrothermograph set up in the dining hall, talking with site personnel, and observing changes in the house through the seasons, we have proposed the following recommendations. To smooth out the wide recorded variations in actual moisture content (a difference of 6 times from winter to summer), the temperature should be kept low during the winter (45–50�F). It should then be easier (i.e., require less humidification) to maintain a higher relative humidity (45–50%) than before. During the summer, dehumidification has to be emphasized in order to maintain a reasonable R.H. (45–50%) and to prevent excessive moisture buildup in the walls. The temperature should be approximately 70–75�F. These limits can be maintained without exorbitant cost or undue stress on the building's fabric. Keeping the temperature and relative humidity within these ranges will mean an annual fluctuation of only 2 times actual moisture content. Furthermore, we also recommend the use of the inherent temperature moderating elements of the historic stucture. In the case of the Martin Van Buren house, the shutters, inside and outside, were meant to be used to insulate the windows, thus inhibiting dramatic changes in temperature. Besides environmental stabilization, the following will help to maximize the longevity of the wallpaper:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSEVEN THOUGH wallpapers, and certainly scenic wallpapers, have been treated in the past, the authors know of no instance where the commitment to full and proper treatment has been as great as with the National Park Service, North Atlantic Region. It has been a pleasure working with such people whose standards and expectations are so high. REFERENCESA. L. Diament & Co., “Historic Notes on the Scenic Papers of the A. L. Diament & Co.” Philadelphia. CatherineLynn, Wallpaper in America, W. W. Norton and Co., New York (1980), p. 274. Ibid., p.232. JamesHamm and Patricia D.Hamm, “Historic Wallpaper in the Historic Structure: Factors Influencing Degradation and Stability,” Conservation Within Historic Buildings, The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, London (1980), p. 173. 4:2:1 Rhoplex AC-33:Rhoplex N-580:distilled water.

Section Index Section Index |