CONSERVATION OF A MONUMENTAL OUTDOOR BRONZE SCULPTURE: THEODORE ROOSEVELT BY PAUL MANSHIPLynda A. Zycherman, & Nicolas F. Veloz

3 TREATMENTTHE TREATMENT we devised7 was designed to improve the sculpture's appearance while complying with the artist's wishes regarding surface treatment (based on the cited memorandum), and to protect and conserve the bronze metal itself. The treatment consisted of the following steps:

3.1 Removal of Surface Accretions and CoatingsTHE COMBINATION of thick, pigmented wax, pollutants and particulates had formed a hard, tenacious black crust on the surface. In an inconspicuous area we tested the solubility of this layer in denatured alcohol, commercial lacquer thinner, VM & P naphtha, gum turpentine and Varsol, a petroleum distillate, BP 150�–170�C. The latter two were quite effective on the wax and dirt but slightly less so on the shoe polish. We decided to emulsify the dirt and wax in a solution of water/gum turpentine (1:1) with 2–5% Igepal, CO-630, a non-ionic wetting agent, and 1% Aerosol-OT, an emulsifier. After some experimentation with scrub brushes, cotton diapers and nylon scrub pads, we found that the most successful method was to lay a soaked diaper compress on the surface, wait 15 minutes for the wax to be emulsified, and then wipe the emulsified wax off with a second saturated diaper. Stiff brushes and nylon pads were essential for cleaning out details such as hair and folds.8 The emulsified wax runoff made the bronze base, the granite pedestal, and the plaza slick and dangerous to stand on. Although periodic hosing with water alleviated the problem somewhat, we decided to eliminate the emulsion treatment in favor of straight gum turpentine applied with diapers and scrub pads. Every inch of the bronze was soaked, wiped and scrubbed repeatedly (Figure 3).

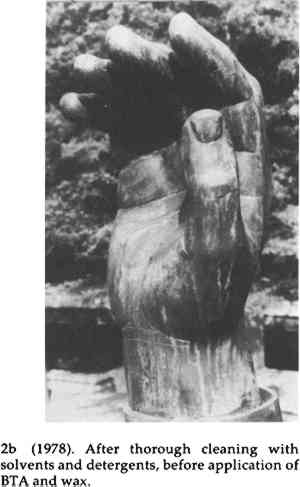

After the first solvent strip, we washed the sculpture, granite pedestal and plaza with a 5–10% aqueous solution of a commercial detergent and grease cutter9 to help remove remaining traces of wax and emulsified run-off. For the second solvent strip the diapers soaked with Varsol remained white, proving that the sculpture was nearly clean, except for the underside of the frock coat and the upper backs of the legs, below the unwaxed corroded join. In these protected and nearly inaccessible areas the wax was still soft and pliable; perversely, because of its easy solubility it smeared, and was even more difficult to remove than the tenacious black crust on the exterior. After a second scrub with detergent followed by a thorough rinse and a third Varsol strip the sculpture was judged free of surface accretions and wax. A final degreasing with white cloths saturated in denatured alcohol completed this phase of the treatment. The appearance of the Theodore Roosevelt at this point was vastly different from that before cleaning (Figure 2b). In protected areas where the wax layer appeared to have been intact prior to cleaning, the bronze was a golden brown color with a light haze of green corrosion in places, instead of a uniform, dull black. The broad surfaces, which now appeared satiny from a distance, showed a pattern of fine concentric lines at closer inspection, most probably the traces of mechanical finishing and polishing. Where the wax had weathered and eroded, the green corrosion was thicker and opaque, with a distinct pattern of brush marks, especially on the shoulders. This could be the result of differential rates of corrosion under an unevenly applied wax coat. Details of the hair and jewelry were once more visible. The depth and extent of the graffiti—swastikas, initials, etc.—became clearer.

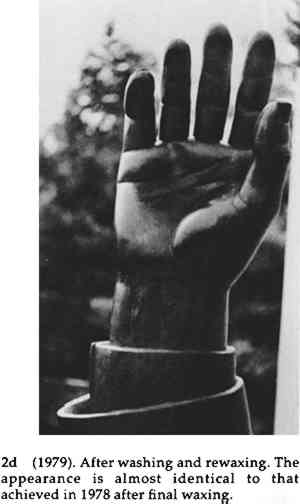

3.2 Patination of Graffiti15% POTASSIUM SULFIDE in water, repeatedly swabbed on cold, was the first solution we tried to color the graffiti, but after rinsing and rubbing with a cotton diaper the resultant brown color was weak. A commercial bronze patination solution10 based on selenious acid gave better results. The desired degree of brown was obtained after a few passes with a swab. The solution was feathered out to visually blend the graffiti with the surrounding metal. The area was rinsed with water and buffed with a diaper. 3.3 Protection Against CorrosionIN OUR OPINION the statue's satisfactory state of preservation was certainly due to its relatively recent and excellent casting. In addition, for this particular bronze in its present location, the protective nature of the wax coating was significant. Therefore, Manship's wishes regarding surface treatment were still a feasible method of preservation for the bronze. However, since we were unsure of semi-annual or even annual maintenance, additional protection against corrosion seemed warranted. We chose benzotriazole (BTA) as the corrosion inhibitor, to be applied directly to the clean bronze surface. We considered, and decided against, using Incralac,11 a well-known lacquer containing BTA, chiefly because of the difficulties we faced with its recommended spray application. The sculpture itself, as well as the setting, constituted the main obstacles to spraying an even lacquer coat. The 30-foot granite shaft stands less than three feet behind the figure, making it impossible to get the manlift cage in between. We were effectively impeded from spray lacquering the back of the figure directly, as well as adequately masking the granite shaft from the over spray. It would have been equally impossible to spray lacquer under the hard-to-get-at folds of the frock coat which, in places, stood only inches away from the legs. Another drawback to using Incralac on the Theodore Roosevelt was that any lacquer coat would be quickly broken by the public climbing on the accessible parts of the statue, and overly frequent touch-ups would be necessary. An aqueous solution of BTA had the advantages of easier application and upkeep while still performing well as a corrosion inhibitor. BTA12 was dissolved in 75:25 warm water/alcohol to make a 3% solution by weight. The alcohol was intended to increase the penetration of the solution by decreasing surface tension. As the solution dried on the surface excess BTA precipitated as white crystals, which were easily hosed off with water. The visual effect of the BTA treatment on the bronze was to make it slightly darker and more uniform in color. As a final protection, we applied two thin coats of a homemade wax paste, formulated for durability and spreadability.13 The wax was applied in the afternoon, when the bronze was warm enough to absorb as much as possible. Following Bearzi's recommended procedure, but using cloths instead of brushes, we smeared the wax in circular motions on the large, smooth areas. In the details, a shoe polish dauber gave better results. We then buffed with clean cloths and soft brushes. This finishing wax treatment darkened the bronze a bit more and diminished the contrast between the heavy green corrosion and the metal. The haze of thin corrosion on the broad surfaces disappeared. The final color was similar to the water-wetted clean bronze (Figure 2d).

|