EARTHQUAKE DAMAGE TO WORKS OF ART IN THE FRIULI REGION OF ITALYPaul M. Schwartzbaum, Constance S. Silver, & Carol A. Grissom

ABSTRACT—In 1976, a series of powerful earthquakes devastated the region of Friuli, located in the northeast corner of Italy. The artistic patrimony of this area was seriously damaged, provoking major conservation problems of both emergency and long-term natures. In collaboration with Italian authorities, the Istituto Centrale del Restauro, Rome (ICR), and the International Centre for Conservation, Rome (ICCROM), American conservators have been active in a number of earthquake-related conservation projects. These include: surveys of and emergency first aid to damaged mural paintings; major treatments of damaged mural paintings; a survey of earthquake-displaced objects; and the creation and operation of a laboratory for the treatment of damaged polychromed sculpture. This paper outlines some of the special conservation problems created by earthquakes and describes a number of conservation efforts to date. 1 INTRODUCTIONIn 1976 a series of powerful earthquakes devastated the northeast corner of Italy, in the region known as the Friuli, as shown in Figure 1. Although seismic faults have made earthquake destruction a recurrent phenomenon in the Friuli, the major earthquakes of May and September 1976 were unprecedented in their force and duration, as shown in Table 1. These earthquakes seriously damaged the artistic patrimony of the Friuli—mainly

Table I Strongest Tremors of the 1976 Earthquakes. 2 A SURVEY OF DAMAGED MURAL PAINTINGSIn the aftermath of the May earthquake, the Istituto Centrale del Restauro and the International Centre for Conservation were requested by the Italian national authorities to assess the damage suffered by the mural paintings, establish conservation priorities, and make treatment recommendations.5 To this end, a joint survey was conducted from July 3–9, 1976. The survey team included conservators, art historians, and an architect.6 Findings were recorded on a prepared form utilizing the following criteria to establish priorities:

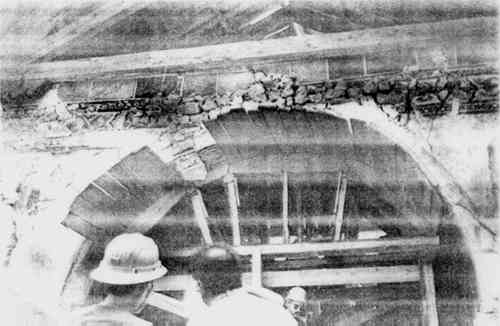

The types of damage encountered in the survey were those usually associated with mural paintings. The major difference was found to be the speed of the deteriorative process: the initial damage (cracks, detachment of layers, lacunae) occurred in a few seconds, and the secondary damage (softening of plaster, powdering of the surface, growth of microorganisms, exudation of salts) often proceeded at a rapid pace when the frescoes were unprotected from the elements. Recommendations were made for ways to stabilize the conditions of the wall paintings. These included the construction of temporary roofs, structural proppings and counterforms; the application of supportive facings; the injection of adhesives; and the collection and storage of fragments. In the extreme cases in which the preservation of the fresco “in situ” did not seem possible, it was necessary to recommend the removal of the fresco.8 3 MURAL PAINTINGS, PRELIMINARY TREATMENTThe following descriptions of the treatment carried out under the auspices of the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti e Gallerie of Griuli-Venezia Giulia, illustrate how the methods chosen were influenced by special earthquake-related considerations, e.g., the probability of further collapse, personal safety, the approach of winter, or demolition schedules.9 3.1 The Church of Saints Giacomo and Anna, VenzoneThe single nave church of Saints Giacomo and Anna was entirely frescoed during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The May 6th earthquake destroyed the roof and weakened the nave walls and the barrel vault of the chancel. In the months that followed, a wooden counterform was placed underneath the vault to support the frescoes, and the unstable nave walls were propped. However, these measures proved insufficient to resist the September earthquakes: the barrel vault settled onto the counterform, the upper portion of the left nave wall collapsed, and the upper portion of the right nave wall leaned outwards at a precarious angle. See figures 2–4.

It was decided that the frescoed barrel vault of the chancel could be preserved “in situ.” A metal roof was constructed to prevent the infiltration of water. Excess masonry was removed from the vault to reduce the weight resting on the counterform.10 To strengthen the vault from above, reinforced hydraulic mortar was applied. This intervention will permit the eventual removal of the counterform and the treatment of the frescoes. The unstable right nave wall was scheduled for demolition because of its proximity to housing. Therefore, it was decided to remove the frescoed decorations.11 A scale drawing was made of the fresco's position on the wall for use in the event that the church is reconstructed. After partial removal of superimposed layers of plaster, two layers of gauze and one layer of heavy hemp fabric were applied to the fresco with “Paraloid B72” dissolved in “Diluente Nitro;” in order to improve the poor working properties of the resin as a result of the cold temperature, it proved necessary to heat the wall prior to application.12 The top border of the hemp was nailed to a board. This was, in turn, secured on the other side of the wall with heavy cording. The system supported the fresco and its preparation during detachment from the wall. The fresco was then transported to Udine for remounting on a new support. 3.2 The Church of San Lorenzo, Villuzza of RagognaAfter the May 6th earthquake, the roof and upper portions of the nave of the Church of San Lorenzo collapsed. Plaster fell from the remaining walls, revealing traces of a previously unknown eleventh century fresco cycle, unique in the Friuli, as shown in Figure 5. Furthermore, the edge of the cliff on which the church was situated had moved to within inches of the left nave wall as a result of earthquake-related landslides. The probability of complete loss of the left wall with further landslides required the immediate removal of its frescoes. However, since the thin, well-adhered preparations of the frescoes precluded “stacco” or “strappo,” the only alternative was a “stacco a massello,” the removal of the painting, preparation, and masonary support as a complete unit.

A team of conservators from the Istituto Centrale del Restauro carried out the following treatment in October, 1976.13 Multiple layers of plaster were mechanically removed from the paint surface. Two layers of gauze were adhered with “Paraloid B72.” Excess masonry was removed from the reverses of the frescoed blocks, and they were consolidated with Since the right nave wall was not in imminent danger, it was treated “in situ” to arrest deterioration and withstand the winter. After partial removal of superimposed layers of plaster, protective facings were applied, the wall was propped, and a small roof was constructed to protect the frescoes from direct contact with the elements. 4 SURVEY OF EARTHQUAKE-DISPLACED OBJECTSImmediately after the first earthquake, emergency depositories were established for displaced objects, mostly polychromed wooden sculptures and paintings on canvas. The largest depository (c. 1500 objects) is located in the church of San Francesco in Udine, a city relatively undamaged by the earthquakes. Many of the objects suffered direct damage from the tremors, e.g., tears, broken extremities, abrasion of relief areas, and imbedded rubble. Many were indirectly damaged from exposure to the elements after the earthquake. Moreover, the conditions in the church have contributed to the degradation of the objects: the relative humidity in the church is constant but extremely high (80–90%), the depository has no facilities for fumigation, and it is overcrowded. Although in the first months following the earthquake some “first aid” measures were initiated, no comprehensive examination and survey of the objects was conducted. Therefore, a survey of the objects in the depository was carried out during the first quarter of 1977 under the auspices of FRIAM.16 Its purpose was to identify objects actively deteriorating and to classify them on the basis of urgency of treatment and transportability. Because of limited time, the survey was restricted to the most severely damaged category of objects: the polychromed wooden sculptures. For the objects requiring major treatment (174), brief examination forms were filled out, accompanied by photographs; for the minimally damaged sculptures or less important pieces (254), brief notes were made. 5 FUTURE PLANS: A CONSERVATION LABORATORY IN CIVIDALEAlthough the Italian authorities have made considerable progress in dealing with the situation, conservation resources remain inadequate to cope with immediate needs.17 Thus. FRIAM is planning a small conservation laboratory staffed with volunteer conservators from the United States.18 Space has been allocated to FRIAM by the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti e Gallerie and the ecclesiastical authorities in the church of San Francesco in Cividale. Objects have been chosen for treatment based on the results of the survey. Fumigation, consolidation, fixation and reassembly will be emphasized. REFERENCESCoordinator, Mural Painting Conservation course, International Centre for Conservation, Via d San Michele 13, 00153 Rome, Italy.

Conservator, c/o Soprintendenza ai Monumenti e Gallerie, Via Aquileia 4, Udine, Italy. Conservator, 5521 Harney Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68132. The vulnerability of the traditional stone rubble construction to earthquake tremors aggravated destruction. According to conservative estimates, 63 churches were destroyed, 247 gravely damaged, and 388 damaged; 5 castles were destroyed, 13 gravely damaged, and 21 damaged; 14 wall painting cycles required very urgent work, 13 urgent work, and 43 moderately urgent work. Estimates regarding buildings: private communication, Riccardo Mola, Soprintendente ai Monumenti e Gallerie of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, March 23, 1977; estimates regarding wall paintings: “Rilevamento dei danni riportati dai dipinti murali del Friuli a seguito degli eventi sismici del maggio 1976,” unpublished report n. 2293, Istituto Centrale del Restauro (with the collaboration of the International Centre for Conservation), 1976. The survey report: “Rilevamenti dei danni …,” etc. (see Footnote 1). Istituto Centrale del Restauro (ICR), Piazza di San Francesco di Paola 9, 00186 Rome, Italy. The ICC was also asked to assist with architectural problems in the Friuli. As a result, architect Donald Del Cid supervised the work of architectural conservation students from the ICC immediately after the May earthquake. The project report: “Presentazione delle relazioni sulle attivit� svolte in Friuli dagli ispettori onorari della Soprintendenza ai Monumenti in collaborazione con il Centro Internazionale per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali, dopo la missione realizzata nella zona colpita dal terremoto del 6 maggio, 1966,” unpublished report, International Centre for Conservation, Rome, 1976. Discussion of architectural damage per Se, however, is considered outside the scope of this paper. Members of the ICR team included art historian Michele Cordaro (team director) and conservators Mara Nimmo and Giuseppe Moro. Members of the ICC team included conservators Paul M. Schwartzbaum (team director), Constance Silver, Katsuhiko Masuda, and Andrea Lidgerwood; art historian Elizabeth Smith Schwartzbaum and architect Donald Del Cid. In November, the survey was revised to reflect the situation after the September earthquakes by P. and E. Schwartzbaum, C. Silver, and D. Del Cid. In the course of the survey, the original form for recording information was continuously revised as a result of experience in the field. The removal of a fresco is somewhat analagous to the transfer of a panel painting in that it is generally considered undesirable except as a last resort. “Strappo” is the removal of only the uppermost pigment-bearing layer; “stacco” is the removal of the fresco and its plaster preparation; “stacco a massello” is the removal of the painting, preparation, and mural support. It is generally desirable to remove as much of the preparation as possible in order to preserve the original character of the wall. “Stacco a massello,” however, is often prohibitively expensive. The Soprintendenza ai Monumenti e Gallerie is the Italian agency responsible for the conservation of works of art in Italy. Under its auspices, mural paintings have received treatment for earthquake-related damage in over 47 churches. Alberto Rizzi, “Scoperte e distruzioni di affreschi in seguito al terremoto in Friuli,” Ce fastu?, 52, 1976, pp. 171–183. Many of these interventions were carried out by the Istituto Centrale del Restauro in September and October 1976 and May 1977 (proposed). In the process very fine early medieval fresco fragments were discovered. These had been used as fill material in the construction of the vault. The removal of the large fresco described in this paper was carried out by Constance Silver with the assistance of Carol Grissom during the last weeks of 1976. Animal glues are traditionally preferred for fresco removal because of their strong adhesive properties. However, they cannot be used under exposed conditions. “Paraloid B72,” known as “Acryloid B72” in the U. S., is the most commonly used synthetic resin in conservation in Italy. “Diluente Nitro” is a mixture of organic solvents with a high percentage of toluene. The team was led by Mara Nimmo and included Constance Silver, who originally alerted the authorities to the importance of the frescoes. Hydraulic cement is not considered the ideal material for use in mural painting consolidation because of the possible exudation of harmful salts, but it was the only material available.

Since each meter contained less than twenty stones, twenty unique arabic numbers were assigned to each meter, e.g., 1–20 for the first meter, 21–40 for the second, etc. Smaller fragments on FRIAM, Friuli Arts and Monuments, is a private American organization funding restoration projects in the Friuli. Directing the organization in Italy is Henry Millon, Director of the American Academy in Rome. In addition to local and national approval, projects are reviewed by Professor Paul Philippot, Director of the International Centre for Conservation. Paul Schwartzbaum, a member of the FRIAM Committee in Italy, has directed the technical aspects of the FRIAM projects described in this paper. The survey was conducted by Carol Grissom. For example, special appropriations by the national government and the establishment of a conservation school and laboratory by the region. Bernard Rabin will be chief conservator, assisted by Carol Grissom, Constance Silver, Laurence Keck, and advanced students from American conservation programs.

Section Index Section Index |