TREATMENT OF A FLOOD-DAMAGED OIL PAINTING ON A SOLID SUPPORTDAVID C. GOIST

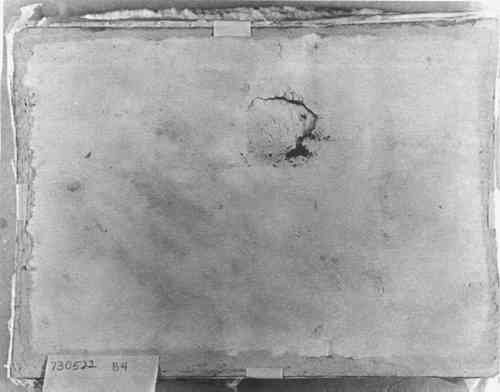

ABSTRACT—The following paper describes the treatment of an oil painting on fiber-board severely damaged by water and mechanical force. The results of the exposure to excess moisture necessitated the removal of the original support and the transfer of the paint and ground layers to a new mount. Traditional transfer techniques often include the addition of materials such as an aqueous ground and a fabric support. These added materials could impose their will on a thinly constructed painting producing effects, either during application or aging, alien to the character of the visible surface and the artist's intent. The treatment decided upon employed a system of materials and adhesives of varying solubilities that would provide a new support more in character with the original, provide security for the painting in the handling process, and insure more ease of reversibility in the future. 1 INTRODUCTIONOne of the many works of art in the collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York, damaged by the floods caused by Hurricane Agnes in June 1972, was a small oil painting entitled NU COUCH� (Marcelle) by the French painter and glass blower, Maurice Marinot (1882–1960). When brought to the Cooperstown Graduate Program in July 1973, the painting was so covered with mud that it was unrecognizable as such. The painting measured 23.4 cm � 32.9 cm and was painted in 1928 during the artist's “period noire” (1912–1937). The signature, date and title were applied to the reverse with a brush and ink. The treatment here described was completed by March 1974. 2 CONDITION PRIOR TO TREATMENTThe painting was received secured in felt-lined grooves of a wooden rack (see raking light, Figure 1), both being thickly covered with dried mud. Tests determined that the paint medium was oil. The support was a 0.4 cm thick fiberboard. Vertical and horizontal warping from shrinkage of the support had resulted in a very rigid 2.6 cm convex distortion in the picture plane. In a 1.0 cm bulge beyond this general warp, at upper center, mechanical force from the reverse had ruptured both fiberboard and paint layers in an area measuring approximately 4.0 cm � 5.0 cm. In and around the rupture and bulge, mechanical cracks, blisters, and cupping existed in the paint layers. There was also cleavage and cupping in many sections around the edge of the support.

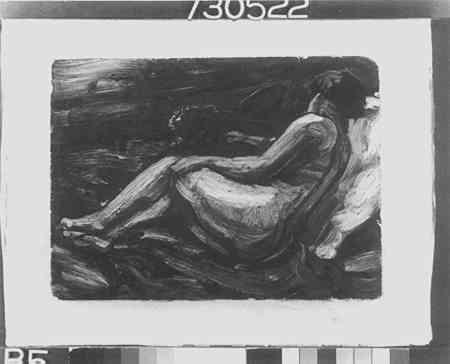

3 TREATMENTThe mud was removed by gently rolling cotton swabs dampened with water plus a wetting agent across the surface. Although a solvent-type natural resin varnish had never been applied, the ample proportion of oil medium in the paint layer allowed relatively easy removal of the mud with all rolling stopped short of the various areas of damage. Removal of the major portion of mud permitted examination of the paint film and thin white oil layer serving as the ground. Shrinkage, warpage and the central rupture cracks Reduction of the distortion in the ruptured area was the first requisite in treatment. That section was faced with two protective layers of shin tenjujo paper adhered with a cornstarch paste. As each paper was applied and dried, it was coated with n-butyl methacrylate resin dissolved in petroleum benzine in an attempt to gain visibility, flexibility and strength to the faced section of damage. The painting was turned face down in the wooden rack in which it had arrived and the fiberboard support was delicately cut away with a scalpel from the reverse of the securely faced ruptured section. The exposed cracked reverse of paint and ground was coated with polyvinyl acetate (AYAC/AYAA, 50:50) in toluene. The addition of thermoplastic films to both sides of the expanded area enabled a response to minimal heat from an infrared lamp, and gradual manual pressure successfully reduced the bulge to conform to the surrounding support. With no disturbance of the facing over the now-flattened rupture, the entire paint surface A negative impression of the paint texture and warp of the support was made with polyurethane foam2 isolated from the facing tissue by very thin aluminum foil. To insure that no undue pressure would be placed on the still vulnerable section, a watch glass was placed over the rupture during the foaming process. The set foam provided a firm, very light weight support during the removal of the remaining fiberboard from the reverse of the painting. Because the reverse bore legends of identification, it was faced in turn and every attempt made to remove its uppermost layers intact. Due to the thinness and brittleness of the support, a one-piece removal was not feasible. The back layer was cut in pieces whenever necessary to avoid possible risk to the paint and ground. At the conclusion of the treatment the portion of the support bearing the writing was patched and backed and returned to the museum. During the slow and cautious removal of the support it became apparent that the artist had occasionally emphasized his design by scratching into his wet paint and thin ground exposing the fiberboard. Such scratch lines were found behind the knees and under the arm of the reclining figure. Their presence increased the fragility of the paint and thin ground. The polyvinyl acetate mixture (AYAC/AYAA, 50:50) in toluene used to reinforce the cracks adjoining the rupture was again employed to strengthen these intentional breaks. Once the rigid support was entirely removed, as shown in Figure 2, the faced paint and

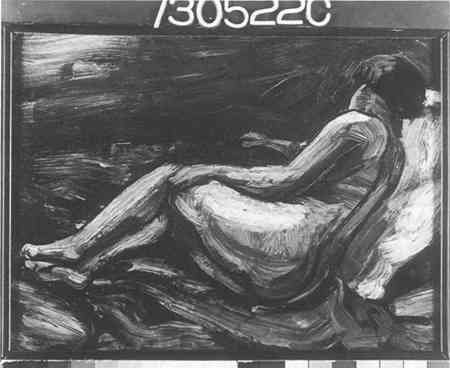

It was presumed that traditional techniques for transfer would introduce gesso cracks or impressions of canvas weave foreign to the special quality of this painting, particularly where the support is visible through the scratched “emphasis lines.” In order to avoid such impressions and maintain a comparable tone in the lines, the following method was employed. A handmade Japanese paper similar in color to the original support was selected. Two sheets each slightly larger than the size of the painting were sized with wheat paste and stretched on a drying board. Rohm and Haas Rhoplex AC-34 acrylic emulsion was considered as a sizing but bypassed due to its tendency to make the paper transparent and lose the desired tone. When the wheat paste and paper were dry, each sheet was coated evenly with the “Hot Melt” adhesive devised by Bernard Rabin.3 With the painting still faced, the reverse was rinsed first with detergent in water then with acetone to provide a clean bonding surface. A thin and even brush coat of “Hot Melt” adhesive was applied to it. After an appropriate lapse of time to permit the solvent to evaporate from the adhesive, each sheet of prepared Japanese paper was attached individually to the reverse on the vacuum hot table. The two-stage attachment proceeded in a manner similar to a standard lining operation under a rubber membrane with the painting face up on the “Hot Melt” side of the Japanese paper. The paper was isolated from the hot table surface each time by mylar film. The result was the faced paint and ground attached to a double thickness of flexible Japanese paper. To assure the consolidation and add rigidity to the new lamination, a 4-ply 100% cotton fiberboard was attached with wax-resin (Multiwax W445/Piccolyte S-85, 2:1) adhesive to the reverse of the double layer of Japanese paper. The 100% cotton fiberboard was first entirely infused with wax-resin adhesive. The attachment was conducted on the vacuum hot table in the same manner as with the previous sheets of Japanese paper. Once the lamination was secured to the fiberboard, the facing was removed with solvents as shown in Figure 3. Small deposits of mud around the edges of the breaks and formerly cupped paint came away with the removal of the facing adhesives.

A balsa core panel was selected to further provide rigidity and security. A birch wood veneer (3/16″ thick) was chosen to sandwich a core of end-grain balsa wood blocks (�″ thick) with four redwood strips serving as a collar. Two veneer sheets cut to the dimensions of the painting were sized with shellac. The end-grain balsa blocks fitted within the redwood collar were glued to one of the veneer sheets with polyvinyl acetate emulsion adhesive. To the other veneer sheet the laminated painting was attached with wax-resin adhesive by means of the vacuum hot table in the manner previously stated. Finally the picturebearing veneer sheet was glued with polyvinyl acetate emulsion to the balsa block surface of the first veneer sheet. The painting received an isolating spray application of Permanent Pigments, Inc. Soluvar brand acrylic resin varnish diluted in petroleum benzine. The small losses of paint were filled with a gelatin and whiting putty. Inpainting was completed in pigments ground in n-butyl methacrylate resin. A “dry” spray of Rohm and Haas Acryloid B-72 resin dissolved in xylene was applied to the finished painting to reduce the gloss and to provide a harder, thus more dust resistant, surface than Soluvar varnish. The painting after treatment is shown in Figure 4.

4 DISCUSSIONWhen it was realized that the removal of the original support from the paint and ground layers was necessary, a treatment was devised using materials that could be applied and removed without affecting one another. The temporary adhesives of starch paste and n-butyl methacrylate were removed with water and petroleum benzine that would not disturb the bond made with the polyvinyl acetate “Hot Melt” adhesive on the reverse of the thin ground layer. The temporary support on the front of polyurethane foam incorporates no solvents, and its exceptionally light weight did not endanger the painting's fragile conformation. Since the slight warmth produced during the foaming might have softened the n-butyl methacrylate facing adhesive, an isolating layer of thin aluminum foil was used. The emulsion glue used to assemble the balsa core panel required only slight pressure during its drying time. The wax-resin adhesive bonding the 100% cotton fiberboard to the new Japanese paper support can be dissolved in petroleum benzine and naphtha to ease disassembly of the lamination components should future reversal of the treatment be required. The initial varnish application, the water-soluble filling putty, and the inpainting medium were all applied in solvents that would not affect the “Hot Melt” adhesive. REFERENCESConservator, Intermuseum Laboratory, Oberlin, Ohio 44074. Rabin, B. “A Poly(Vinyl Acetate) Heat Seal Adhesive for Lining.” Conservation and Restoration of Pictorial Art. Edited by N.Brommell and P.Smith. pp. 165–68. London: Butterworths, 1976. Stephan foam H-106 (R and T components), Stephan Chemical Company, Northfield, Ill. 60093.

Section Index Section Index |