Shades and Shadow-Pictures: The Materials and Techniques of American Portrait Silhouettes

by Penley KnipeThis paper's research project began as a third-year intern project in the paper laboratory at Yale Center for British Art and the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG). The effort to study American portrait silhouettes originated with a YUAG curator's interest in silhouettes as a possible addition to a planned exhibition of portrait miniatures. This, combined with the author's interest in folk art and the fact that silhouettes have been little studied from a materials point of view, drove the project forward. Since that time the collections at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFAB); the Fogg Art Museum; and the American Antiquarian Society have also been studied. American portrait silhouettes proved to be more than charming. The history and diversity of silhouette manufacture was compelling; silhouettes were made freehand and with tracing devices, by amateurs and professional artists alike. The issue of where these objects fit within the overall context of portraiture was also of interest.

The term silhouette is well understood now, though this was not always the case. Early designations included "shade," and "profile." Lesser known names were: "miniature cuttings,"1 "black profile,"2 "scissortypes,"3"skiagrams,"4 "shadowgraphs,"5 "shadow portrait,"6 "shadow picture,"7"black shade,"8 or simply "likeness,"9 Those who cut silhouettes were sometimes called "profilists". Auguste Amant Constant Fidèle Edouart, the famous French silhouettist, referred to himself as the "black shade man" perhaps ironically as he detailed the disdain many held for him after they learned of his trade but had yet to see the excellent quality of his work.10

The name "silhouette" derives from the surname of an eighteenth-century finance minister to Louis XV who, in 1757, lasted a mere eight months in his post due to his financial conservatism.11 Etienne de Silhouette's stringent monetary tactics proved overwhelmingly unpopular and as a result things that were considered miserly or simply cheap became labeled as à la Silhouette. It is often suggested in the literature that the connection with the art was further cemented by Silhouette's own penchant for cutting profiles as a hobby, though this may simply be folklore.

It is likely that Edouart purposefully popularized the name "silhouette" when he came to England in 1829 from France.12 He wanted to create the impression of something new—he sought specifically to distinguish his work from the popular "shade" which was often traced by machine, a method he found crude and meritless.13Even after the term "silhouette" was introduced, "shade" did not go out of fashion—Queen Victoria called her 1834 album a collection of shades.14 In fact, Edouart reported in the 1830s that once outside England's urban areas, the name "silhouette" meant little to the people he encountered.15

The earliest known silhouette was probably of William and Mary done by Elizabeth Pyburg in the late seventeenth-century England.16 During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were numerous well-known English silhouettists who usually painted their subjects onto a variety of substrates such as ivory and plaster. These artists include John Field, Isabella Robinson Beetham, John Miers, and Charles Rosenberg. The most well-known silhouettist of all was undoubtedly French-born Edouart, who worked in England and the United States. The silhouette also flourished in other parts of Europe. In Germany the artist Philipp Otto Runge made both painted and cut portrait bust silhouettes and paper cut-outs of botanical specimens, animals, scenes, landscapes, and full figures. The French artist Jean Huber cut intricate and complex landscapes and historic and tableau scenes from both paper and parchment.

The history of the art is engaging, in part, because of the diversity of the silhouettists themselves. These small keepsakes were made by both professional artists and amateurs. Some well-known dabblers included Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,17 Hans Christian Anderson,18 and Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King George III.19 There were delicately cut silhouettes by trained artists such as William Henry Brown, William Doyle, and Raphaelle Peale, the latter relying on a tracing device. Another machine-aided silhouettist was Moses Williams, the ex-slave of Charles Willson Peale, who ran a tracing machine at the popular Philadelphia Peale museum. There were the silhouettists such as Master Hubard, an untrained English child prodigy, who masterfully cut silhouettes from the age of thirteen "without the least aid from Drawing, Machine, or any kind of outline."20 Finally, there were the countless unnamed ordinary people who cut or painted silhouettes of their friends and loved ones. That members of the royalty, scholars, anonymous amateurs, and learned and self-taught artists were all making silhouettes speaks to the wide variety of types and skill levels encountered when studying these objects.

Description

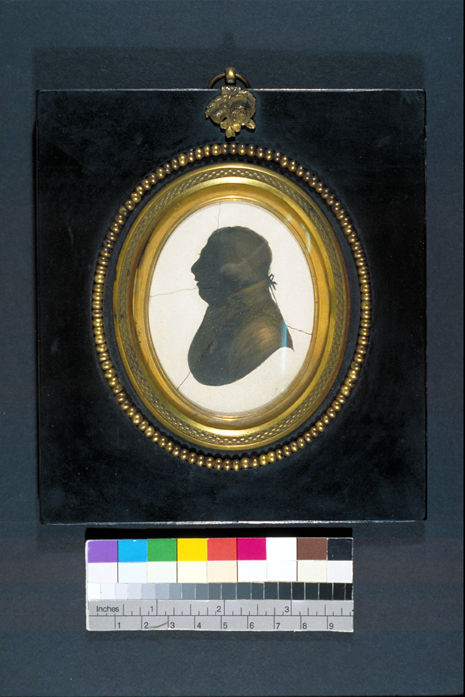

Fig. 1. Example of a painted silhouette. John Miers (England, 1758-1821), Silhouette of a Man facing Left (proper right). Black watercolor or ink bust silhouette with gold color on plaster. Gift of Helen Foster Osborne, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1981.470.

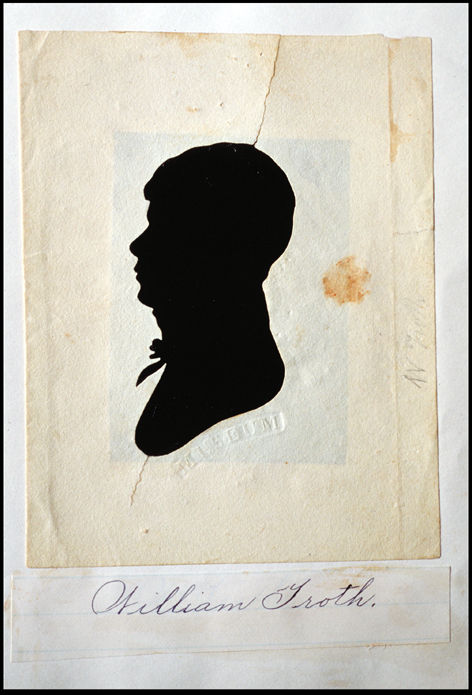

Fig. 2. Example of a hollow-cut silhouette. Peale Museum, William Groth (?), facing left (proper right), c. 1802-10. Hollow-cut bust silhouette from beige wove paper backed with black shiny wove paper (mounted in album of silhouettes). Gift of Azita Bina-Seibel and Elmar W, Seibel, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1999.238.9.

Fig. 3. Example of a cut-out silhouette. Samuel Metford (United States, 1810-1890), Thomas Goddard (1765-1858). Cut-out full-figure silhouette from matte black coated white wove paper with graphite, opaque watercolor and white paper insert (collar) mounted to a lithograph. Bequest of Maxim Karolik, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1964.1139.

One goal of the project was to standardize the nomenclature that describes silhouettes. For the purposes of this project, silhouettes that are drawn or painted (usually in black) onto a substrate are called "silhouette" (fig. 1). For example, a bust painted in black ink on a piece of paper or plaster falls into this category. "Hollow-cut silhouettes" refer to silhouettes cut from a piece of paper, usually light colored, so that the middle, the positive, drops away leaving the negative, the outside of the image, which is then backed with dark paper or fabric (fig. 2). Alternatively, those silhouettes in which the image is cut from a dark material, usually black paper, and mounted onto a substrate, such as a heavy cream-colored card, are called "cut-out silhouettes" (fig. 3).

Those objects that have evidence of having been traced with a machine with graphite or a metal point are described as "with graphite tracing" or "with stylus tracing." Silhouettes decorated with a gold or with inked-in hair are described as "with" gold color or "with" black ink. If the paper used is known to be painted or coated, or is particularly matte or glossy, that information is also included.21

Fig. 4. Example of a conversation piece silhouette. Auguste Amant Constant Fidèle Edouart (France, 1789-1861), William Buckland and his Wife and Son Frank, Examining Buckland's Natural History Collection, c. 1828-9. Cut-out full-figure silhouettes from matte black coated white wove paper mounted to beige wove paper. Mary L. Smith Fund, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1966.964.

Besides type and media, a third important facet of silhouette description is format. Silhouettes, like portrait sculpture, are usually either busts or full-figure. Hollow-cuts are always bust length whereas silhouettes and cut-outs are found in both formats. There are "conversation piece" silhouettes which show a group, such as a family, in a customary setting like a drawing room (fig. 4). This type of scene was a popular painting format in the eighteenth century. Conversation pieces are comprised of individually cut-out full-figure silhouettes as well as the cut-out accessories of domestic life, such as chairs, tables, toys, and books.

The History Of Silhouettes22

There are many hypotheses about the historical precedents of silhouettes. The profile images from ancient Egypt on tomb walls and in Greece on vases are oft cited silhouette sources. In the eighteenth century, Neoclassicism had revived interest in this simplified form of portraiture. In reaction to the excesses of the Baroque and Rococo styles and spurred on by the discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 1748, the antique sensibilities were a favorite during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The use of profiles on antique coins and medals may also be a source. These influences can be seen in the porcelain of Josiah Wedgwood, in Empire-style dresses, in the architecture of John Nash and Robert Smirke, and in painting and drawing by artists like Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

The aesthetic connection between things antique and silhouettes is further solidified by an 1815-16 silhouette cutting instruction book. The samples for copying found in Introduction to the Art of Cutting Groups of Figures, Flowers, Birds, &c. in Black Paper (London) very clearly draw from the antique. The figures are clothed in Empire-style dress, are posed in positions suggesting classical sculpture, and have the accouterments of "ancient" life such as vases, decorative columns, and empire furniture.

The following Greek myth recounted by Pliny the Elder also serves as a silhouette source.23 It is the story of the Corinthian maid Dibutade who outlined her departing lover's shadow on the wall to preserve his image whilst he was away. The maid's father Butade filled the outline with clay and fired it with the rest of his pots in order to comfort his lonely daughter—Pliny used the story to illustrate the origins of clay modeling. By the eighteenth century, the myth became popular as a depiction of the origins of painting and the subject was depicted by such artists as Joseph Wright of Derby, Joseph-Benoît Suvée, and Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson.

The years that this myth was popular, 1770s till 1820s, coincided directly with the height of silhouette interest. Reducing features to elegant "antique" outlines and simple black shapes was very stylish. In an 1801 lecture at the Royal Academy in London, the artist Henry Fuseli made the connection between silhouettes and the Greek tale clear when he declared:

If ever legend deserved our belief, the amorous tale of the Corinthian maid, who traced the shade of her departing lover by the secret lamp, appeals to our sympathy. . . . the first essays of the art [painting] were skiagrams, simple outlines of a shade, similar to those which have been introduced to vulgar use by the students and parasites of Physiognomy, under the name Silhouettes.26

Fuseli's words point to another source of interest in silhouettes, the "science" of Physiognomy. Physiognomy was first discussed in Johann Caspar Lavater's 1770s treatise, "Essay on Physiognomy, for the Promotion of the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind."25 Lavater, a Zurich evangelical minister, expounded the belief that moral and spiritual character could be studied in the human face and the most accurate vehicle for examining the countenance was through the machine-traced silhouette.26 The first American edition of Lavater's treatise was published in Boston in 1794. Six years later a celebrated abridgment was printed, The Pocket Lavater. These publications helped spread Lavater's theories and, in turn, further popularized the silhouette.

Silhouettes became popular for reasons beyond the study of physiognomy. This form of portraiture held significant advantages over others, the foremost being expense. As opposed to portrait miniatures made with precious pigments on ivory or vellum and housed in expensive cases, shades were often simply snipped from paper for a few pennies. Another advantage was accuracy, which was dependent, of course, on a skilled silhouettist or a reasonably adept snipper with a precise tracing machine. The speed with which one could get a portrait taken was the real clincher. Only one sitting was required, as compared to numerous sittings needed for more complex forms of portraiture, and often the sitting was brief. The quickness of the individual artist was occasionally featured in their advertisements. For example, Sam Weller claimed that with his "profeel machine" he could finish a portrait and frame it, complete with a hanging hook, within two minutes and fifteen seconds.27 Even the meticulous English artist John Miers, whose silhouettes were delicately painted on plaster or ivory, only required a three minute sitting.28 It is these advantages that were improved upon by photography which, not long after the public announcement of its invention in 1839, dealt a deadly blow to silhouettes as the portrait medium of choice.

Silhouettes were also readily available. In England, the artists congregated at fashionable places such as London and Bath, where "society" frequented. Like their English counterparts, the American silhouettists, both the learned and self-trained, gathered in summer resort areas such as Gloucester and Newport, hoping to gain referrals from their initial clients. Many itinerant silhouettists were able in a number of ventures. Some were tinkers, peddlers, or sign painters. For example, William King advertised as a profilist and a provider of electric-shock treatment, the latter service being rather popular at the time.29 Silhouettists often advertised in the local papers, staying in populated areas for a few weeks or months before moving on.30

The major silhouettists working in this country were William James ("Master") Hubard and Edouart, Raphaelle Peale, Moses Williams, William Bache, Moses Chapman, William Doyle, Henry Williams, William King, and William Henry Brown. Silhouettes, first made in the 1760s or 1770s, became very popular in the 1780s. By 1803, a large number of both itinerant and stationary artists were available to cut silhouettes all over the Eastern United States.31 In fact, prior to the arrival of Edouart in 1829, there were already over forty artists cutting silhouettes, some by hand and others with the help of a tracing device. The craze died down after the first decade of the nineteenth century. Interest in silhouettes revived in the 1830s and it may well be that Edouart was essential to this revitalization, as he cut portraits of some of the most influential people of the time.32 However, the tradition of silhouettes in this country was already well established.

It has been suggested that the hollow-cut was both developed and used exclusively in America.33 While it is true more hollow-cuts were done in this country whereas silhouettes were frequently painted or cut-out in England, there was cross-over, especially with the small but significant number of artists who worked in both countries. It is also true that cut silhouettes (hollow-cut or cut-out) were more popular in the nineteenth century whereas the earlier silhouettes tended to be painted, often on ivory, and clearly derived from the portrait miniature tradition, especially in England during the first two-thirds of the Georgian Period. The subject of national styles of silhouettes is significant and it deserves further study to understand fully the overlaps, similarities, and distinctions.

Before discussing presentation, materials, and techniques, a brief examination of the life and practices of the best-known silhouettist introduces essential themes of this research. The facts surrounding Edouart's life are well documented and need only be touched on here.34 He was born in France in 1789. In 1814, Edouart went to England to find employment. After making intricate pictures with hair, he turned to silhouette cutting in 1826, after the chance occurrence of discovering his talent for silhouette cutting: Edouart apparently cut a silhouette to illustrate to friends, enchanted by a machine-aided shade, that he could hand-cut one superior to the clumsy specimen of their admiration. Edouart enjoyed success in Great Britain and he set sail for America in 1839 and remained for a decade.

Edouart preferred to cut the whole figure because through demeanor and dress, more of a likeness could be captured. However, Edouart's labels listed prices for bust silhouettes so he must have cut them, though they are much less common than his full-figure cut-outs.35 Edouart also often included personal affects such as a eyeglasses or a cane to make the portrait a more personal depiction. He often mounted his silhouettes on lithographed scenes done by "artists (. . . not inferior ones)."36 Edouart was also a meticulous record keeper, writing all of the information five separate times on the back of the silhouettes, in his records, and in the indexes to those records. He kept duplicate books that contained every silhouette he cut—like many artists, he folded the paper at least once, with the black side in, before cutting so that two (or more if the paper was folded more) silhouettes were produced. One went to the customer and the second went into Edouart's duplicate album. During Edouart's 1849 return to England, there was a ship wreck in which the artist survived but many of these duplicate albums were lost. The artist died in France in 1861.

Many sources state that Edouart simply looked at the sitter and snipped away. In fact, Edouart drew his subjects with graphite on the white side of the paper.37 Again, the paper was folded so the black was on the inside which protected its delicate surface—it was also easier to draw on the white side of paper than on the black side. Edouart often painted the edge of his silhouettes with a black medium that appears shinier and perhaps distinct from the medium used to coat the paper. He did this to get rid of the distracting appearance of the white paper core. Though Edouart thought little of "touching" up a silhouette with decoration, he did it, not infrequently.38 He decorated more often with chalk or graphite and less with a gold colorant. One finds the detailing much more frequently on objects made after 1840, when the artist had to compete with photography.39

Silhouette Presentation

How were silhouettes presented and kept? Some were kept in albums or scrapbooks. According to historian Anne Verplanck, by 1700 the practice of keeping albums was common and it continued into late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Albums started as signature books which could contain pasted or pinned-in silhouettes and slowly shifted into scrapbooks full of clippings, cuttings, and the occasional silhouette. In this country, Verplanck found album compilation to be particularly popular among the Quakers.40 At the time silhouettes were popular it was certainly possible to acquire blank books commercially. Silhouettists themselves kept albums as well. As mentioned, Edouart kept copies of his cut-outs in albums though he strongly advised his patrons to frame their silhouettes. He wrote:

The beauty of those Likenesses consists in preserving the dead black, of which the paper is composed, and scratches, rubs, or marks of fingers . . . take away a great deal. . . . I advise those who wish to preserve the Likenesses to have them framed as soon as possible (to avoid marring) for those who put them in ScrapBooks, I must forewarn them, it is a practice injurious to cuttings inas much as they are too libel to be handled and even destroyed by the rubbing of fingers.41

Not all silhouettes ended up pinned into scrapbooks. Because of their inexpensive nature, relative ease of acquisition, and because a sitter often acquired more than one portrait at a time, silhouettes could be given to someone as a memento. For this purpose, silhouettes were kept loose and later housed by the recipient in some fashion. Often these loose silhouettes were slipped into the family bible or a favorite book. As Edouart advised, many silhouettes were framed and hung on the wall. It was often possible to purchase the frame along with the silhouette at the time of the sitting—often clients chose a reverse glass gold and black painted mat as well.

Both William Henry Brown and Edouart mounted many of their cut-out silhouettes onto lithographed backgrounds. The scenes were of domestic, work, or scenic outdoor spaces. In 1846, Brown published Portrait Gallery of Distinguished American Citizens, a publication of twenty-six of the most important of his sitters, including Daniel Webster, Thomas Hart Benton, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. E.B. and E.C. Kellogg of Hartford, Connecticut, well-established lithographers who often printed the backgrounds for Brown's cut silhouettes, made lithographs of the silhouettes for this book. Edouart employed another well-known set of lithographers, Unkles and Klason, to produce his backgrounds.42 Edouart also hand-drew some of his mounts in styles similar to the lithographs. Other artists such as Hubard and Jarvis Hankes mounted their cut-outs to plain cards and then connected the sitters firmly to the earth with a wash of watercolor and even a watercolor cast shadow. Other types of mounts encountered were embossed or decoratively painted.

Fancier style silhouettes can be found. There are wonderful images sculpted in wax or painted on ivory, card, plaster, or glass. Silhouettes were painted on ivory and housed in decorative miniature cases. These types of silhouettes were obviously much more labor-intensive and expensive than paper silhouettes. Painted silhouettes decorated jewelry, such as brooches and rings, and snuff boxes. Silhouettes were also found on contemporary dishware and on mourning cards.

Materials

The materials and technology of creating silhouettes were extremely varied. The materials ranged from plain, off-white wove paper from which a hollow-cut was fashioned and mounted over a fabric scrap to the patented portable Facietrace machine used by Rembrandt Peale to trace profiles.43 However, little is written about the historic techniques. This may simply be because the general technology was relatively straight-forward and available to anyone with a pair of embroidery scissors and a scrap of paper. Research did reveal snippets of nineteenth-century information and plenty of twentieth-century information from which glimpses of earlier technology may be gleaned.

Paper

The paper used to make cut-out silhouettes is relatively thin and black on one side, white on the other. The black colorant is usually a coating sitting on the surface of the paper. The coating is relatively thick,44 matte, opaque, and it appears somewhat dry, as if it is leanly bound. There are very often small chunks of a black material which visually looks like bone black—this was confirmed by analysis, as described below.45 Occasional brush strokes can be seen on many of the samples. While there is some variation in these coatings from silhouette to silhouette, often papers used by different artists appear very similar. That is, some papers appear uniformly coated with the matte black medium in a manner suggesting commercial production. It is important to note that there are silhouettes cut from paper that appears more crudely or differently colored and these papers were probably coated by the artist.

Paper conservator Jane Smith Stewart undertook a research project during a summer work project at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) to investigate the black coated paper used by Edouart, paper which fell into the category of possibly being commercially produced. Together with Smithsonian Center for Materials Research scientist Walter Hopwood, Stewart analyzed samples from three Edouart cut-out silhouettes from the NPG's collection. The research revealed that the papers were coated with a combination of pigments and binder. The pigments were a mixture of bone black and Prussian blue with a binder of silica and waxes, possibly paraffin and/or beeswax. Parenthetically, the adhesive used to affix the cut-out silhouette to its secondary support was probably a gum (arabic, ghattti, or tragacanth).46

This author had the occasion to show some of the YUAG silhouettes to Stewart. What was noted was that the YUAG Hubard Gallery and Edouart47 silhouettes appeared very similar to each other and to the Edouart samples that Stewart tested from the NPG. This past year, at the MFAB, five silhouettes with black papers that were visually similar to those used by Edouart were chosen for analytical testing: four by the Hubard Gallery48 and one by Samuel Metford.49 The reason for testing was to see if the papers used by different artists contained the same components as those found by Stewart. If so, this could strengthen the case that some silhouette papers were produced commercially, which might in turn be revealing about the market and economics of silhouette cutting. That is, were enough silhouettes being produced to justify a papermaker producing this paper?

MFAB conservation scientists Richard Newman and Michele Derrick and this author analyzed the coatings from the five silhouettes using Fourier-Transform Infrared Reflectography (FT-IR; see figure 5).50 The four coatings from the Hubard Gallery contained bone black and all but one had Prussian blue as well.51 The binders from the Hubard Gallery silhouettes were more difficult to determine using FT-IR—some of the samples suggested wax and others suggested protein.52 The Metford coating was like the NPG examples in that it contained bone black, Prussian blue and was possibly bound with wax. In three of the five samples from the MFAB, gypsum, possibly added as a cheap filler, was also found. Stewart did not find gypsum on the NPG examples, but she did find silica, which we did not.

The components found did not differ greatly from what Stewart discovered in the Edouarts from the NPG. That is, the pigmentation was usually achieved by a mixture of bone black and Prussian blue. However, there are enough significant variations to suggest that no single commercially produced paper was used by these professional silhouettists.

Documentary evidence for commercial silhouette paper was also sought in the examination of trade catalogues at the American Antiquarian Society, with particular attention being paid to stationer or artists' material trade catalogues from 1800-1875. While decorative papers, colored tissue, and lightly tinted papers in colors like violet, gray, and fawn were found, this sleuthing did not turn up any appropriate silhouette papers.53 John Krill of the Winterthur Museum kindly reviewed his research on artists' supplies done in England on the period 1840-1900 at the archives of Winsor and Newton and several London museums. He also found no mention of such a paper.

Complicating the situation is the fact that, as of yet, the author has not found any mention of how to make or acquire the black paper in the historic literature. If artists were preparing the coating themselves using variations on the bone black and Prussian blue recipe, why is there no mention of this? In the earliest book found on the subject, Introduction to the Art of Cutting Groups of Figures, Flowers, Birds, &c. in Black Paper (1815-16), the author Barbara Anne Townshend simply writes that one should use either "thin black paper, either dyed or shiny according to taste."54 Parenthetically, Townshend also writes that one should cut from the white side of the paper, so she was referring to coated rather than dyed paper. In the 1836 edition, the author states, "the paper best calculated for this use is thin black paper, either dyed black or glazed."55 Townshend goes on to provide detailed information about how to set up compositions and how to cut figures versus flowers, but the paper is mentioned as if acquiring it were no bigger problem than a walk to the local stationer's.

The question of whether the paper was commercially available remains for now unanswered, and with that questions about whether the popular art was indeed popular enough to warrant commercial manufacture of paper for its use. However, based on visual similarities between papers, the absence of directions for coating paper in the literature, the even and somewhat sophisticated appearance of the coatings, and the wide range of paper products available, it is probably that some black coated papers were commercially available. These papers were used by some of the silhouettists because their businesses were busy enough to be able to both afford and require such paper. Conversely, some artists and many amateurs simply made the coated paper themselves.

Twentieth-century sources on silhouette paper revealed that in 1938 one could acquire a silhouette paper called "krome kote," which usually had a white pre-gummed verso for affixing the silhouette to a secondary support .56 A number of modern sources referred to "surface paper" which was described as thin, evenly black on one side and white on the reverse.57 In 1953, Quimby suggested that though requesting "silhouette paper" could get just a blank stare from the clerk at the stationers, it did exist.58 One can still get silhouette paper today. It is an American-made product that comes from American Craftlines and is available through Dick Blick in packages of 25 sheets (measuring 10" x 15"). The paper has a matte, rich black surface on one side and is white on the other. Testing of the paper revealed that it contains purified ground softwood and alum, is slightly alkaline, and that the color is not water soluble.59

The paper used for hollow-cuts was most often cream-colored and wove, though laid paper was also used. Watermarks, usually only partial because of the smallness of the objects, are occasionally encountered. For example from watermark evidence it is known that the Peale family consistently used wove paper from the Thomas Amies Mill on a Schuylkill River tributary.60 This author's examination of eighty-nine hollow-cuts by William Chamberlin revealed the use of many different papers; they were all cream, but some were rough while others were smooth, some were thin and others were substantially thicker. Some, though not all, of the wove papers were machine-made. From the fragmentary watermark evidence, it is also clear that the papers were from numerous mills.

Some hollow-cuts are made from laid paper. That laid paper was sometimes used was somewhat surprising—one might think that wove paper, readily available from the 1790s, would have been decidedly more desirable for its more uniform, smooth texture that would have been less distracting visually. However, the use of both laid and wove paper simply reinforces that silhouette cutting was a common art; it was practiced by many different classes of people with widely varying aesthetics and artistic concerns, access to materials, seriousness of endeavor, and financial means.

The backings for hollow-cuts were usually black and often from a household material such as a textile fragment or a scrap of paper. It is common to find backings unattached, that is, the hollow-cuts are simply laid on top of the backings. Some paper backings were matte black while others are very shiny. The occasional blue backing was also found and encountered in the literature.61 It was not unusual, as well, to find unbacked hollow-cuts that have either been separated from their backings or were never backed.

Pigments

Some of the dark-colored media used to decorate silhouettes, color a backing paper, or blacken a paper for cut-outs were probably purchased while others appeared to be home-made. References both to commercially-available colorants and to recipes for making colorants were found in the literature—overwhelmingly the colorants referred to are either lamp black or India ink which are, themselves, closely related as they both are made from carbon black.62 One early source, from 1814, recommends an iron gall ink—"a sort of black ink fit for painting figures, and to write upon stuffs, and linen, as well as on paper" containing gall-nuts, white wine vinegar, and iron filings, with or without gum arabic—but its use on silhouettes is not common.63 As is more the norm, an 1835 encyclopedia names India ink as the silhouette black of choice.64 Silhouette historian Neville Jackson stated that India ink made with pine soot, beer or tallow smoke was used.65 Two other authors suggested that a rich, velvety black was obtainable by the same ingredients of beer mixed with lamp black or soot.66 Vernay cited lamp black specifically as the colorant used by an 1826 silhouettist.67 Prepared dry, watercolors were certainly obtainable commercially from the early eighteenth century,68 the cake form was available by the late eighteenth century, and moist pan watercolors were developed around 1815.69 As with the other materials, it is reasonable to presume that while many nineteenth-century silhouettists may have availed themselves of the commercial products, others made the colorants themselves.

Decoration

Many silhouettes were enhanced by the addition of gouache or ink to add details to the portrait such as eyelashes, hair ribbons, and shirt collars. From their beginning, hollow-cuts were frequently detailed by inked-in hair and eyelashes, for example. On the other hand, cut-outs were more frequently decorated after 1840 in order to compete with photography. Many artists decorated their silhouettes with graphite, ink, whites, (especially for frilly collars), or gold color, the latter called "bronzing"70 or "touching."71 Sometimes the treatment of the detailing is enough to secure an attribution—for example, William Chamberlin's hollow-cuts have a very consistent and distinctive treatment of the shirt collar in ink.

The media used for detailing are rather diverse. Whites were described in the literature as being done in watercolor and sometimes more specifically in Chinese white,72 a form of zinc white which was available commercially around 1834.73 Stewart found the whites on the Edouarts she analyzed to be an inorganic silicate like kaolin or talc with traces of organic material, so clearly dry white media were also being used.74 The practice of doing accents in gold was usually done in shell gold which is gold powder mixed with gum arabic to form a watercolor and it has been available since medieval times.75 Bronze powder may have been used as well, though less frequently. Bronze powder is a metal flake pigment made from numerous copper alloys, the combinations of which give varying tonalities of gold, which has been available for a long time, but only cheaply from the 1860s, a date rather late for silhouettes.76

Scissors

Most of the many sources which mentioned specifics about scissors were from this century. The one exception, an early nineteenth-century book on black paper cutting, stated that scissors must have long shanks with short, sharp points.77 The twentieth-century references stressed both that the scissors be somewhat loose on the hinge to give the cutter flexibility and dexterity to change direction with ease78 and the importance of choosing good quality scissors.79 Mention was also made of specially-constructed silhouette scissors which were reportedly hard to acquire in this country.80 Fiskars, a Finnish company which has been making scissors since 1830, reported making special order silhouette scissors from carbon steel on rare occasions and general paper cutting scissors more regularly.81 Nel Laughon, a silhouette historian and modern-day practitioner, reported that scissors made specifically for silhouette cutting were made in Germany. She also suggested that there was little consistency as to the scissors used because people used whatever was available to them.82 This is no doubt true for those who were not making silhouettes for profit—people picked up whatever they had at hand. The professional artists, however, probably had supplies devoted to their trade. The most likely scissors used were those for needlework as these tended to be small and sharp with long handles relative to the short tips, again for ease of manipulation and for short, well controlled cuts. Again and again in the literature, embroidery scissors are mentioned and they were the known choice of Edouart.83

That knives were used to do some cutting is well established.84 Coke, a silhouette historian, goes so far as to say that the early work was done with a knife, rather than scissors.85 Reference was also made to the use of a stiletto, which is an awl or stylus, in combination with scissors.86 Needles were apparently also used for very fine work.87 While it is often possible to tell which side of the paper a silhouette was cut from, based on the edge's curl and compression, it is more difficult to determine what tool was used. In an experiment by the author, a knife and scissors made clean, satisfactory cuts while a needle tended to drag the paper causing a frayed edge, but perhaps the needles used historically were more suited to the task. Examination of some of the finest cutting on silhouettes of the period does suggest a tool other than scissors must have been used, simply based on the small scale of some details within which it would have been very difficult to manipulate even a pair of small scissors. It is highly likely that a small knife or sharp needle was often employed, especially for details.

Tracing Devices

One of the most interesting parts of silhouette history is the mechanical means of capturing a profile. The original apparatus, developed in France by Gilles-Louis Chrétien in 1786, was brought to this country in the 1790s by a group of French émigrés.88 Many of the early tracers were used for capturing a profile for small engravings or to get the general countenance down prior to painting a miniature. Saint-Mémin, for example, used a device called a physionotrace for the tracing and reducing of a profile for portraits and very small engravings.89

The best known example of a tracing device was the physiognotrace developed by John Isaac Hawkins. Hawkins gave the device to Charles Willson Peale, along with the Philadelphia rights to it, for promotional purposes to be used in the Peale Museum.90 Peale, a man of many talents and extraordinary energy, opened a museum in Philadelphia in 1785, from which he hoped to fashion a series of national museums for democratic education in arts and sciences. The Philadelphia version was extremely popular and well attended. By 1802, besides exhibiting portraits of distinguished Americans, minerals, fossils, a mastodon skeleton, wax figures of Indians, war equipment, and anatomical deformities, there was Hawkins's physiognotrace at one end of the Long Gallery.91 Guests could help themselves and make their own hollow-cuts or they could get assistance from Moses Williams, Peale's ex-slave. Eventually almost everyone wanted Williams to make the silhouette for them, a service for which he charged eight cents. It should be said that Charles Willson Peale may never have traced or cut a silhouette himself, but the family name (or "Peale Museum") is generically used as an attribution of these objects, as often the actual cutter is not known.92

According to Peale, having one's silhouette taken by the device was the rage from 1802-1805 and it remained fashionable through the first decade of the nineteenth century.93 After that time, enthusiasm waned somewhat though silhouettes made with tracing devices remained moderately popular until supplanted by the camera in the 1840s.

John Hawkins's machine differed from Chrétien's and others in that it traced around the actual face with a small bar (an "index" made of brass) which was connected to a pantograph that simultaneously reduced the silhouette to nearly two inches. Examination of a reproduction of the physiognotrace revealed the opening where the paper fit in was about 4" x 4".94 Evidence suggests that four hollow-cuts were often done at one time by twice folding the paper.95 Peale explained the device in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in January 1803:

The person to be traced, setting in a Chair, rests their head on the concave part, & the hollow of the board below imbraces the shoulder—The Physiognotrace is fixed to the board, A at a, and in the center of the joint b, is a conic steel point with a spring to press it against the paper. . . .This index moving round to trace any subject that the edge is kept too, as it moves, the steel point of the upper joint, gives a diminished size a perfectly correct representation.96

Though Hawkins and the Peales tried to protect the physiognotrace from being copied through patents, there were many versions being used all over the East Coast, some of which pre-dated Hawkins's. Peter Benes writes, "scores of portraitists, artists-entrepreneurs, and mechanicians rushed to take advantage of the popularity of cheap, machine-made profiles."97 Many contraptions were very similar and could claim only fraudulent improvements over Hawkins's patented version, while others were truly different. Some used optical projection, like the camera obscura, to capture a profile on paper which, while being traced, was reduced with an attached pantograph at the same time. This had the advantage of not being "scraped with the machine"98 as when the brass index of Hawkins's machine passed over one's features. One such invention is described below:

The operator placed the sitter in a darkened room and projected the profile against a paper-covered pane of glass by means of a single light source positioned at the far end of a five foot 'trunk' or box. The pantograph traced the sitter's shadow . . .the other end traced a smaller image on a sheet of paper.99

Lavater, the physiognomist who preferred the anatomical correctness of traced profiles, even developed a special chair to hold sitters still while their shadows were traced. Though physiognotrace was the commonly used term for these tracing mechanisms, there were other names for the various inventions, including the Ediograph, Limomachia, Pasigraph, Prosopographus, Profilograph, Charles Schmalcalder's Delinator, Copier, Proportionometer100 and William King's "patent delineating pencil."101

When examining hollow-cuts it is often possible to find evidence of a tracing apparatus. Either a graphite or metal tip was generally used and there are often areas around the outline of the face where traces of graphite or the indented line from a stylus are visible. Since the profiles were cut after tracing, often some or all evidence of the tracing tip has been trimmed away. Also, since multiple hollow-cuts were made at once, frequently it is only the top piece of paper that bears the evidence. Hollow-cuts have another characteristic that can reveal their traced roots: they tend to be more generically and formulaically handled than other silhouette types, something that becomes apparent after looking at silhouettes even briefly.

Blind Stamps, Trade Labels, and Forgeries

Fig. 6. Detail of hollow-cut silhouette showing "Museum" blind stamp. Peale Museum, William Groth (?), facing left (proper right), c. 1802-10. Hollow-cut bust silhouette from beige wove paper backed with black shiny wove paper (mounted in album of silhouettes). Gift of Azita Bina-Seibel and Elmar W. Seibel, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1999.238.9.

The professional silhouettists like Edouart, Metford, Hubard, and the Peales often employed a stamp or label to identify their silhouettes. For example, the silhouettes cut at the Peale museums or by one of the Peales traveling with a physiognotrace were often stamped with one of three blind stamps, the most common being "MUSEUM" (fig. 6). "PEALE'S MUSEUM" and "PEALE" were the other stamps used, the former with an eagle with outspread wings.

Most of the time these stamps can be relied upon, but like any artist's signature or identifying mark, there are those that are not what they purport to be. For example, Yale has a hollow-cut bust silhouette on beige-colored machine-made wove paper and backed with an unattached black textile. The sitter is George Washington.102 Underneath the bust, there is a blind stamp of an eagle with out-stretched wings and the words "PEALE'S MUSEUM" underneath. The hollow-cut paper measures 5 7/8" x 5". This silhouette is a 1920s forgery of which there are numerous examples, with slight variations but sharing certain telling characteristics.103 The silhouettes are almost twice as large as a proper Peale silhouette and they share the stamp used first legitimately by Rubens Peale in New York from 1825-1837.104 The stamp was acquired in the 1920s by New York antique-store owners Mr. and Mrs. Collins and it is believed that the Collinses forged many Washington hollow-cuts. The stamp's placement on the fakes is lower and because the silhouettes are bigger, the stamp is smaller relative to the hollow-cut; on the authentic silhouettes the stamp is as wide as the base of the silhouette. The silhouette has other features that are similar to other fakes and distinguish it from real "Peale" silhouettes: the broadness of the cutting, the handling of the queue ribbons, the straight nose, and the undefined collar. That is, the cutting is less than delicate and is more generic.105 Another reason for skepticism about the Washington silhouettes is due to the variations seen in the fakes; if the silhouettes were mass-produced for sale at the Museum(s) as mementos of the Nation's father, they would likely all be the same. Nor is the fact that the figure is of national importance and the silhouette is "by" a famous name insignificant. Only these high-end fakes could command a price worth the effort in such a "cheap" art.

Some labels tell more than simply the artist, the location and the price. Some, like those of Hubard are rather enlightening. Consider these two: "Cut with common Scissors, BY MASTER HUBARD, (aged 13 years) Without Drawing or Machine"106 and "This curious and much admired Art of cutting out Likenesses with common Scissors, (without drawing or machine) originated in this Establishment, in 1822."107 They remind the viewer that the artist was a child prodigy and that he didn't rely on a machine to get his portraits. This latter point is an important distinction. Many of the free-hand artists felt their profiles were superior to and distinct from the hollow-cut silhouettes done with a tracing device.

It is not simply that one must rely on labels and stamps and the occasional signature to assign artists. When studying silhouettes, there is definitely a style to certain artists that becomes apparent the more one looks. For example, Edouart left us many telltale signs of his work. The men usually have slit button holes and cut away collars with a piece of white paper inserted underneath. The figures' feet are usually long, thin, and dangling. As mentioned, Chamberlin had a signature collar he both cut and then drew on. Often the way the base of the bust of a hollow-cut is handled can be a clue. Certain artists cut a small notch in the bust or shaped it in a characteristic way. For all the talk of the mass production or cheapness of this art, many of the silhouettists, like any artist, had individual styles. Still, there are thousands of silhouettes crafted by now-anonymous people, perhaps the sitter's sister, perhaps a traveling profilist/sign and banner painter.

Conclusion

Silhouettes played an important role in portraiture in the United States in the last decades of the eighteenth century through the mid-nineteenth century. They were an economically reasonable alternative to portraits painted in oil and portrait miniatures. For many, silhouettes were the first type of portraiture available to them—the price was within reach, the artists came to their areas, and the medium was popular as well as fashionable. In many cases, the silhouette remains as the sole portrait of an individual.

Silhouettes are still made today. Helen and Nel Laughon from Virginia travel the East Coast to cut shades at local craft fairs, historic homes, and museums. Carol Lebeaux does the same in New England and is part of a four member group called S.C.O.N.E. (Silhouette Cutters of New England). The silhouette also informs contemporary art. Kara Walker, the celebrated young artist, has taken the tradition of silhouette and has turned it on its head. Whereas historic silhouettes were usually straight-forward portraits, Walker uses the silhouetted image, either of cut paper or by lithography, to illustrate multi-layered narratives of slavery and race. Jin Lee, an Illinois artist, makes photograms of silhouetted women's heads which link ideas about race, identity, and the associated assumptions we make about people. Toby Kamps writes, "Although Lee's works are traditional in form, they also address a thoroughly contemporary set of concerns. . . . Lee's images also allude to historical attempts to employ photography to categorize, exoticize, or commodify individuals or groups of people."108 Silhouettes are no longer just a mode of rendering a likeness. Rather, they are a living art in both the popular culture of the quaint and in the more elite world of art.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks are due to many people who were helpful with this project: Theresa Fairbanks, Robin Jaffe Frank, Richard Field, Lisa Hodermarsky, Erica Mosier, Jane Stewart, John Krill, Roy Perkinson, Annette Manick, Richard Newman, Michele Derrick, Craigen Bowen, Eugene Farrell, Georgia Barnhill, Betty Fiske, Debbie Hess Norris, Dana Hemmenway, Miriam Stewart, Jenna Webster, Edward Saywell, Neville Thomson, Robin Hanson, Judy Walsh, Virginia Whelan, Lance Mayer, Gay Myers, Sarah Dove, Sue Welsh Reed, Helen & Nel Laughon, Carol Lebeaux, Robert Baldwin, Elizabeth Fairman, Gisela Noack, Matt Cutler, Ann Wagner, Lillian Miller, and Helen Sheumaker. I am also indebted to Daniel Abramson for his patient assistance and encouragement.

Notes

1. Helen and Nel Laughon, "Shadow Portraits of George Washington," Antiques (February 1986): 402.

2. Auguste Edouart, A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses (London: Longman and Company, 1835), 3; David Piper, Shades: An Essay on English Portrait Silhouettes (New York: Chilmark Press, 1970), 12.

3. Leonard Simms, The Art of Silhouette Cutting (London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1937), ix.

5. Albert H. Harrison, The History of Silhouettes and How to Make Them (St. Louis: Compiled by the Freelance Publicity and Syndicating Bureau of St. Louis, 1916), 4; F. Gordon Roe, Women in Profile: A Study in Silhouette (London: John Baker, 1970), 24; Simms, ix; Arthur S. Vernay, The Silhouette (New York: Arthur S. Vernay Gallery, 1991), 3; E. Neville Jackson, The History of Silhouettes (London: The Connoisseur, 1911), 7.

6. E. Neville Jackson, Silhouettes: Notes and Dictionary (New York: Charles Scribners and Sons, 1938), 3.

7. Marion Nicholl Rawson, Candleday Art (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1938), 238.

8. Edouart, 3; Ellen G. Miles, "1803 - The Year of the Physiognotrace," in Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast, Peter Benes, ed. (Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1994), 125.

9. Edouart, 7; Leonard Morgan May, A Master of Silhouette (London: Martin Seckler, 1938), 81.

11. R.L. Mègroz, Profile Art through the Ages: A Study of the Use and Significance of Profile and Silhouette from Stone Age to Puppet Films (New York: Philosophical Library, 1949), 87 & 91; Piper, 9.

12. Henry Fuseli used the term "silhouette" in 1801 in London. This challenges the popular belief that the term was introduced to England around 1825 by Edouart. That Fuseli was Swiss and was educated on Continental Europe may account for his earlier use of the term. Edouart was probably responsible for popularizing the term in England, as mentioned.

13. Edouart, 10-11. It must be said that although Edouart generally held machine-made silhouettes in contempt, he commented that, having seen the Mayers' of London machine-derived silhouettes that were enhanced afterward by hand, he felt not all such silhouettes were "completely devoid of interest," 101.

15. Andrew Oliver, Auguste Edouart's Silhouettes of Eminent Americans 1839-1844 (Charlottesville: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, 1977), xi.

16. Peggy Hickman, Silhouettes (New York: Walker and Co., 1968), 5; Mègroz, 87; Roe, 54; Simms, ix.

18. Hubert Leslie, Silhouettes and Scissor-Cutting (London: John Lane, 1939), 14.

19. Ethel Stanwood Bolton, Wax Portraits and Silhouettes (Boston: The Massachusetts Society of Colonial Dames of America, 1914), 35; Piper, 56.

20. James Hubard, A Collection of the Subjects Contained in the Hubard Gallery (New York: D. Fanshaw, 1824), no page number.

21. Descriptions of objects can get rather long and complicated. A typical hollow-cut description might read: hollow-cut bust silhouette from beige wove paper with graphite tracing and black ink, backed with matte black coated white wove paper.

22. For more information about silhouette history, see Alice van Leer Carrick, Shades of Our Ancestors (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1928) and A History of American Silhouettes: A Collector's Guide, 1790-1840 (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1968); Peggy Hickman, Silhouettes and Silhouettes: A Living Art (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975); Jackson, History and Notes and Dictionary.

23. Bolton, 27; Hickman, Silhouettes, 5; Piper, 53. For more information about the story of Dibutade and related imagery, see Frances Muecke, "'Taught by Love': The Origin of Painting Again," Art Bulletin 81 (1999): 297-302; Robert Rosenblum, "The Origin of Painting: A Problem in the Iconography of Romantic Classicism," Art Bulletin 39 (1957): 279-290.

25. For more information of Physiognomy and Lavater, see: Johann Caspar Lavater, Essay on Physiognomy; for the Promotion of the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind (London: C. Whittingham, 1804); Joan K. Stemmler, "The Physiognomical Portraits of Johann Caspar Lavater," Art Bulletin 75 (1993): 151-168.

26. This was in spite of the fact his friend Goethe, an amateur silhouettist, thought little of machine-aided "shades". Piper, 10.

27. Carrick, Shades of Our Ancestors, 11.

28. This is according to one of his labels. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1939.178.

29. Peter Benes, "Machine-Assisted Portrait and Profile Imaging in New England after 1803," in Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast, Peter Benes, ed. (Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1994): 146.

30. For more on the itinerant artist, see: Joyce Hill, "New England Itinerant Portraitists," Itinerancy in New England and New York, Peter Benes, ed., (Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1984): 150-171; For an excellent discussion of the professional life of one silhouettist, see Georgia Brady Barnhill, "Journals of Ethan A. Greenwood: Portrait Painter and Museum Proprietor," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1993): 91-178.

31. Lillian B. Miller, ed. The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 2, part 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 479.

33. Richard L. Wright, Hawkers and Walkers in Early America (New York: F. Ungar Publishing Co., 1965), 140.

34. For more information on Edouart, see: Edouart; Helen and Nel Laughon, "A Newly Identified Edouart Folio," Antiques (December 1984): 1446-1450; Laughon, "Notes and Documents: Auguste Edouart: A Quaker Album of American and English Duplicate Silhouettes," Antiques (1985): 387-398; Oliver.

35. 1828 Edouart Album, Fogg Art Museum, 1980.61.

37. Laughon, "Newly Identified Edouart Album," 1449-50, fig. 8 note and fig. 9 illustration.

39. Personal communication with Nel Laughon, July 28, 1997. Helen and Nel Laughon are a mother-daughter team of silhouette cutters and silhouette historians.

40. Anne Ayer Verplanck, "Facing Philadelphia: The Social Functions of Silhouettes, Miniatures, and Daguerreotypes, 1760-1860" (Ph.D. diss., The College of William and Mary, 1996), 87-88, 92.

43. Miller, vol. 2, part 2, 711 note 1.

44. Jane Smith Stewart found that the Edouart samples she looked at were approximately 30µm (micrometers). Jane Smith, "Conservation Analytical Laboratory Characterization of Three Silhouettes from the Auguste Edouart Album of Eminent Americans," Poster Presentation, American Institute for Conservation Annual Meeting, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1995 (Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1995).

45. Bone black is known to be difficult to grind, as opposed to the more fine lamp black, and it is not uncommon to find small chunks of the charred bone.

46. Jane Smith, "Technical Analysis of Black Coatings on Auguste Edouart Silhouettes," abstract. American Institute for Conservation Preprints, 23rd Annual Meeting, St. Paul, MN, (Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1995): 107.

47. Yale University Art Gallery, Hubard Gallery 1947.336-.342, .346-.348; Edouart, 1947.343-.345.

48. With silhouettes bearing the name or label of Master Hubard, it is safest to assign them to the Hubard Gallery as it is hard to determine who did the actual cutting, unless the silhouette is clearly early (and then it is by Master Hubard). Hubard, born in England in 1807, began cutting at age 13 or 15. After creating a stir in the British Isles as a child prodigy, he came to New York in 1824 with a Mr. Smith, Hubard's sponsor who ran the "Gallery of Cuttings and Panharmonicum." The Gallery was a collection of various paper silhouettes by Hubard of people, animals, architecture, etc. and the Panharmonicum was reputed to be a musical mechanism that could play 206 instruments. In 1825 the show went to Boston; the Gallery of Cuttings and the Panharmonicum was advertised regularly in Boston papers until the end of March 1826.

Hubard was probably no longer associated with Smith and the Gallery after January 1828. The Gallery of Cuttings and Panharmonicum continued on—Master Hanks took over that same year and it is likely Hanks left by 1829. There was apparently a group of young cutters associated with the Gallery, so again, a Hubard Gallery attribution is the most inclusive way to assign these works. Many thanks to the Laughons for telling me about the cutters other than Hanks and Hubards. Laughon, letter to the author, October 19, 1997.

The Hubard Gallery cut-out silhouettes are made from plain matte-black paper mounted to a secondary support, often a card. The Gallery produced full-length and bust silhouettes. The full-lengths silhouettes on card often have a watercolor wash including a shadow underneath the sitter. Not infrequently the silhouettes were modestly decorated with a gold colorant to emphasize buttons, collars, etc.

49. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Hubard Gallery, 1981.472, .473, .475; Samuel Metford, 1964.1139.

50. The instrument used was a Nicolet 510P FT-IR spectrometer with a Nic-Plan IR microscope. 100 scans were taken per sample.

51. Prussian blue was used to counter the brownness of bone black, that is, to help make the bone black appear blacker.

52. Because of the small size of the objects, it was decided not to resample to determine the binders specifically using a chromatography technique. In part this was also decided because the information about the pigments and the preliminary information about the binders already revealed that the coatings on these objects differed somewhat from the Edouarts that Stewart tested.

53. The stationer and artists' material catalogues examined included Cotton, Boston, 1830, 1839, & 1850; M.J. Whipple, Boston, 1851; Frost and Adams, Boston, 1875; Gibbs Brothers, Holyoke, no date; Wheeler and Whitney, Boston, c. 1860; Marshall A. Lewis Co., no date; H. Cohen, Philadelphia, 1859; N.E. News Company, Boston, 1873; John E. Pettybone, Chicago, no date; Corlies Macy and Co., New York, 1874; Louis Snider, Cincinnati, no date; Willy Wallachs, New York, 1874. I am grateful to Judy Walsh for pointing me in the direction of the AAS.

54. Barbara Anne Townshend, Introduction to the Art of Cutting Groups of Figures, Flowers, Birds, &c in Black Paper (London: Printed for Edward Orme, 1815-1816), no page number.

55. Barbara Anne Townshend, Sybil-Leaves or Drawing Room Scraps (London: Adolphus Richter and Co., 1836), 1.

56. Laurene Rose Diehl, Scissor Silhouettes (Waterloo, Iowa: The Rose Leaf Publishing Co., 1938), 15. Also, Harrison notes that he acquired such a paper from Dennison Manufacturing Company. Harrison, 7.

57. Leslie, 25; Mildred Swannell, Paper Silhouettes (London: George Philip and Son, 1929), 2.

59. Dick Blick, #2630006. The paper was tested with the Tri-test kit for unpurified groundwood, alum, and acidity. An Abbey pH pen and a surface pH electrode meter (Beckmann, Zeromatic SS-3) were also used. A fiber sample was examined under the polarizing light microscope at 65X revealing that the fibers are purified groundwood (stained blue with Graff's C-Stain) and well-beaten. As no vessels were observed, the wood is probably a softwood. The specific wood(s) used could not be determined due to lack of visible detail, beyond border pits. Through personal communication with Jim at American Craftlines, 7/9 & 7/11/97 the author was told that the fibers are wood, the sizing is starch, and the coating is a water-based pigment.

This paper was considered a candidate for replacing lost or degraded hollow-cut backing papers, such as for the Yale University Art Gallery silhouette of Augustus Street (1916.2) by an anonymous artist. In the end, a paper from Light Impressions was used because there was more information available about it and it was not alum-sized, though it was somewhat thicker than what was used historically. The paper selected was Light Impressions, TrueCore Card Stock, item number 7670. It is acid and lignin-free. Fiber examination showed both cotton and wood. The C-stain indicated there was purified wood and cellulose. Testing with the surface pH electrode meter showed the pH to be near neutral though Light Impressions specifications list the pH at 8-9.5. The paper passed the Photo Activity Test as well, according to Light Impressions.

60. Charles Coleman Sellors, "The Peale Silhouettes," American Collector, (May 1948): 6. The MFAB recently acquired a small album of hollow-cuts and profile portraits and ten loose, unbacked hollow-cuts (1999.238.1-.22). Four of these were from the Peale Museum and had fragments of Amies watermarks. For information on the Amies mills and their watermarks, see Thomas Gravell and George Miller, A Catalogue of American Watermarks, 1690-1835 (New York: Garland Publishing Company, 1979).

61. Yale University Art Gallery, 1947.440 & .441; Mègroz, 91; Laughon, "Washington," 402.

62. Historically, lamp black usually refers to carbon black, (from various flame sources) gum arabic, with glycerin added by the 1830s. India or Indian ink is most often described as a mixture of carbon black, gum arabic, and a fish content like isinglass or fish bones, and after a certain date shellac (or another resin) was also added. Of course, the ingredients vary from recipe to recipe. Some sources include: Norman Nash, The Artist's Assistant (Springfield: (s.n.) 1810), 53-54; John Payne, Instructions in the Art of Painting in Miniature on Ivory (London: Robert Laurie and James Whittle, 1797), 13-15; Valuable Secrets Concerning Arts and Trades: or Approved Directions, from the Best Artists . . . (Norwich, Connecticut: Printed by T. Hubbard, 1795), 66.

63. John Norman, The Artists' Companion, and Manufacturer's Guide, Consisting of the most valuable secrets in Arts and Trades (Boston: E.G. House for John Norman, 1814), 82.

64. Francis Lieber, Encyclopedia Americana. A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics, and Biography (Philadelphia: Desilver, Thomas, and Co., 1835), 403.

65. Jackson, Silhouettes, Notes and Dictionary, 4.

67. Vernay, The Silhouette, 11.

68. John Krill, letter to the author, 9/12/97.

69. Majorie Cohn, Wash and Gouache: A Study of the Development of the Materials of Watercolor (Cambridge, MA: The Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Fogg Art Museum, 1977), 54.

71. Vernay, The Silhouette, 4.

72. Max von Boehn, Miniatures and Silhouettes (London: E.M. Dent and Sons, Ltd.), 198; Blume J. Rifken, Silhouettes in America: 1790-1840 (Burlington, VT: Paradigm Press, 1987), 2.

73. Gettens and Stout, 176-7; Cohn, 13.

75. Kurt Whelte, The Materials and Techniques of Painting. Trans. Ursus Dix (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, Co. 1967), 622. According to Gettens and Stout, shell gold was also bound with egg white. Gettens and Stout, 116.

77. Townshend, Introduction to the Art, no page number.

78. Carrick, Shades of our Ancestors, 8; Leslie, 28; Lieber, 88.

79. Sister Mary Jean Dorcy, A Shady Hobby (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1944), 14; Simms, 11-12.

81. Olavi Linden of Fiskars, letter to the author, October 15, 1998.

82. Personal communication with Nel Laughon, July 28, 1997.

83. Bolton, 35; Diehl, 8; Leslie, 26; Oliver, xiii; Piper, 32.

84. Carrick, Shades of Our Ancestors, 8; Dorcy, 14; Christian Rubi, Cut Paper, Silhouettes, and Stencils (New York: Van Nostrand and Reinhold, 1972), 83.

89. Miles, 131, 133. The French name is "physionotrace" whereas the English name is "physiognotrace."

For more information on Saint-Mémin's use of the physiognotrace, see Ellen Miles, Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America. Dru Dowdy, ed. (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994).

91. An 1818 broadside reads: "The Profile Cutter attends every day and evening. —Frames furnished at the door."

Peale's Museum. Peale's Museum, in the State House, Philadelphia Broadside, (Philadelphia, April 1818.)

92. Williams cut from 1802 until approximately 1813 and there were at least two others who worked the physiognotrace, Elizabeth Hampton in 1827 and Elizabeth Meigs in 1834. This information is from the curatorial file at the National Portrait Gallery on the Peale silhouettes. I am grateful to Lillian Miller for allowing me to peruse this file. The information is also found in William Reese's 144th catalogue vis-a-vis a small album of Peale silhouettes in Americana: 100 Rare Books, Manuscripts and Prints, catalogue 154 (New Haven: William Reese and Company, no date.) Reese gives a less specific date range, stating that Hampton and Meigs worked at the Museum in the 1820s and 30s.

93. Miller, part 2, vol. 1, 537.

94. The reproduction device was examined at the exhibition, The Peale Family. Creation of an American Legacy 1770-1870, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, April 25-July 6, 1997. It was in a case so exact measurements were not possible.

95. Personal communication with Lillian Miller, May 8, 1997; Miller, vol. 2, part 2, 917. The author has seen an example of two Peale hollow-cuts on one piece of paper with a fold at center. The hollow-cuts are the mirror images of each other and were folded, one on top of the other, while in the physiognotrace (Private Collection).

96. Miller, vol. 2, part 1, 481-2.

101. For an excellent discussion of tracing machines, see Miles, "Physiognotrace," 1994; Benes. Benes includes a useful index of artists and dates with the names of the tracing devices they used.

102. Yale University Art Gallery, 1945.260.

103. For more information on Washington silhouettes, including the fakes see: Laughon, "Shadow Portraits of George Washington."

104. Most of this information, unless otherwise noted, is from the curatorial file on the Washington fakes at the National Portrait Gallery. Again, I am most grateful to Lillian Miller for access to this information.

105. Much of this information was provided by Lillian Miller, letter to the author, July 7, 1997.

106. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William James Hubard, 1981.475.

107. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William James Hubard, 1981.473.

108. Jin Lee, Book of Heads, (Illinois: Illinois Art Council and Illinois State University Research Grant, 1998).

Selected Bibliography

An American Heritage: American Silhouettes. Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, July-August 1973.

Antiques. "Profilist's Progress," vol. 13, 3, March 1938: 149-150.

Barnhill, Georgia Brady. "Extracts from the Journals of Ethan A. Greenwood, Portrait Painter and Museum Proprietor." Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1993: 91-178.

Benes, Peter. "Machine-Assisted Portrait and Profile Imaging in New England after 1803." Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast. Peter Benes, ed., Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1994.

Boehn, Max von. Miniatures and Silhouettes. trans. E.K. Walker, London: J.M. Dent and Sons Ltd., 1928.

Bolton, Ethel Stanwood. Wax Portraits and Silhouettes. Boston: The Massachusetts Society of the Colonial Dames of America, 1914.

Brinton, Anna Cox. Quaker Profiles, Pictorial and Biographical: 1750-1850. Lebanon, PA: Pendle Hill Publications, 1964.

Brown, William Henry. Portrait Gallery of Distinguished American Citizens. Hartford: E.B. and E.C. Kellogg, 1846.

Carrick, Alice van Leer. Shades of Our Ancestors. Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1928.

________. A History of American Silhouettes: A Collector's Guide, 1790-1840. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1968.

Coke, Desmond. The Art of the Silhouette. London: Martin Seckler, 1913.

Columbian Museum. Columbian Museum, Milk-Street. Boston, Broadside, 1804.

The Dictionary of Art. Volume 28, New York: Macmillan Publishers, Ltd., 1996: 713-714.

Diehl, Laurene Rose. Scissor Silhouettes. Waterloo, Iowa: The Rose Leaf Publishing Company, 1938.

Dorcy, Sister Mary Jean. A Shady Hobby. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1944.

Dunlap, William. History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States. New York: G.P. Scott and Co., 1834.

Edouart, Auguste Amant Constant Fidèle. A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses. London: Longman and Company, 1835.

Fouratt, Mary Eileen. "Ruth Henshaw Bascom, Itinerant Portraitist." Itinerancy in New England and New York. Peter Benes, ed., Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1984: 190-211.

Forgione, Nancy. "'The Shadow Only': Shadow and Silhouette in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris." Art Bulletin 81 (1999): 490-512.

Gettens, Rutherford and George L. Stout. Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopedia. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1966.

Grant, James and John Fiske. Appleton's Cyclopaedia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1887-1889.

Groce, George C. and David H. Wallace. The New-York Historical Society's Dictionary of Artists in America 1564-1860. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957.

Guyton, W. Lehman. An American Heritage: American Silhouettes. Hagerstown, Maryland: Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, 1973.

Guyton, W. Lehman and James M. Koenig. A Basic Guide to Identifying and Evaluating American Silhouettes. Waynesboro, Pennsylvania: The Museum, 1980.

Harrison, Albert H. The History of Silhouettes and How to Make Them. St. Louis: Compiled by the Freelance Publicity and Syndicating Bureau of St. Louis, 1916.

Hickman. Silhouettes. New York: Walker and Co., 1968.

________. Silhouettes: A Living Art. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975.

________. "The Andrews Collection of Silhouettes." Connoisseur vol. 295, 822 (1980): 237-241.

Hill, Joyce. "New England Itinerant Portraitists." Itinerancy in New England and New York. Peter Benes, ed., Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1984: 150-171.

Hubard, James. A Catalogue of the Subjects Contained in the Hubard Gallery. 2nd edition, New York: D. Fanshaw, 1825.

Jackson, E. Neville. The History of Silhouettes. London: The Connoisseur, 1911.

________. Silhouette. Notes and Dictionary. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1938.

Johnson, Allen, ed. Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Scribner, 1961.

Knittle, Rhea Mansfield. Early Ohio Taverns; Tavern-sign, Stage-coach, Barge, Banner Chair and Settee Painters. Ashland, Ohio: private printer, 1937.

Laliberté, Norman and Alex Mogelon. Silhouettes, Shadows, and Cut-outs. New York: Reinhold Book Corp., 1968.

Laughon, Helen and Nel. "A Newly Identified Edouart Folio." Antiques (December 1984): 1446-1450.

______. "Shadow Portraits of Washington." Antiques (February 1986): 402-409.

______. August Edouart: A Quaker Album. Richmond, Virginia: Cheswick Press, 1987.

Leslie, Hubert. Silhouettes and Scissor-Cutting. London: John Lane, 1939.

Lieber, Francis. Encyclopedia Americana. A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics, and Biography. Philadelphia: Desilver, Thomas, and Co., 1835.

Lister, Raymond. Silhouettes. An Introduction to their History and to the Art of Cutting and Painting Them. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, Ltd., 1953.

May, Leonard Morgan. A Master of Silhouette. John Miers: Portrait Artist, 1757-1821. London: Martin Secker, 1938.

Mayer, Ralph. A Dictionary of Terms and Techniques. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1969.

McCormack, Helen G. "The Hubard Gallery Duplicate Book." Magazine Antiques (February 1944): 68-69.

________. William James Hubard. Richmond, VA: Valentine Museum, 1948.

McKechnie, Sue. British Silhouette Artists and their Work, 1760-1860. London: P. Wilson for Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

McSwiggan, Kevin. Silhouettes. Buckinghamshire, England: Shire Publications, Ltd., 1997.

Mègroz, R.L. Profile Art through the Ages: A Study of the Use and Significance of Profile and Silhouette from Stone Age to Puppet Films. New York: Philosophical Library, 1949.

Miles, Ellen G. "1803—The Year of the Physiognotrace." Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northeast. Peter Benes, ed., Boston: Boston University and The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings, 1994: 118-137.

Miller, Lillian B., ed. The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family. Vols. 1-2., New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

Oliver, Andrew. Auguste Edouart's Silhouettes of Eminent Americans, 1839-1844. Charlottesville, VA: Published for the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian by the University Press of Virginia, 1977.

The Peale Family: Creation of a Family Legacy 1770-1870. Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, April 25-July 6, 1997.

Peale's Museum. Peale's Museum, in the State House, Philadelphia. Broadside, April 1818.

Piper, David. Shades: An Essay on English Portrait Silhouettes. New York: Chilmark Press, 1970.

Quimby, Nellie Earles. Beauty in Black and White: An Artist with Scissors. Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, Inc. 1953.

Rawson, Marion Nicholl. Candleday Art. New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1938.

Reese, William. Americana: 100 Rare Books, Manuscripts and Prints. Catalogue 154. New Haven, Connecticut: William Reese and Company, no date.

Rifken, Blume J. Silhouettes in America, 1790-1840: A Collector's Guide. Burlington, VT: Paradigm Press, 1987.

Roe, F. Gordon. Women in Profile: A Study in Silhouette. London: John Baker, 1970.

Romaine, Lawrence B. A Guide to American Trade Catalogues. New York: R.R. Bowker, 1960.

Rosenblum, Robert. "The Origin of Painting: A Problem in the Iconography of Romantic Classicism." Art Bulletin 39 (1957):279-290.

Rubi, Christian. Cut Paper, Silhouettes, and Stencils: An Instruction Book. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1972.

Schmidt, George. Mr. George Schmidt's Method of Teaching the Art of Psaligraphy: By Self-Instruction. Boston: L. Prang and Company, (1868?).

Sellors, Charles Coleman. "The Peale Silhouettes." American Collector (May 1948): 6-8.

Simms, Leonard A. The Art of Silhouette Cutting. London: Frederick Warne and Co., Ltd., 1937.

Smith, Jane. Technical Analysis of Black Coatings on Auguste Edouart Silhouettes. Abstract. American Institute for Conservation Preprints, 23rd Annual Meeting, St. Paul, MN, Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1995: 107.

Smith, Jane. "Conservation Analytical Laboratory Characterization of Three Silhouettes from the Auguste Edouart Album of Eminent Americans." Poster presentation. American Institute for Conservation 23rd Annual Meeting, St. Paul, MN. Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1995.

Stewart, Jane Smith: see Smith, Jane.

Swan, Mabel M. "A Neglected Aspect of Hubard." Magazine Antiques. Vol. 20, 4 (October 1931): 222-223.

Swannell, Mildred. Paper Silhouettes. London: George Philip and Son, 1929.

Townshend, Barbara Anne. Introduction to the Art of Cutting Groups of Figures, Flowers, Birds, &c. in Black Paper. London: Printed for Edward Orme, 1815-16.

______. Sybil-Leaves or Drawing Room Scraps. London: Adolphus Richter and Co., 1836.

Vernay, Arthur S. The Silhouette. New York: Arthur S. Vernay Gallery, 1911.

______. American Silhouettes by Auguste Edouart: A Notable Collection of Portraits Taken Between 1839-1849. New York: Arthur S. Vernay Gallery, 1913.

Verplanck, Anne Ayer. "Facing Philadelphia: The Social Functions of Silhouettes, Miniatures, and Daguerreotypes, 1760-1860." Ph.D. diss., The College of William and Mary, 1996.

Whelte, Kurt. The Materials and Techniques of Painting. Trans. Ursus Dix, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, Co. 1967.

Williamson, George C. The History of Portrait Miniatures. 2 volumes. London: Bell, 1904.

Woodiwiss, John. British Silhouettes. London: Country Life, Ltd., 1965.

Wright, Richardson Little. Hawkers and Walkers in Early America: Strolling Peddlers, Preachers, Lawyers, Doctors, >Players, and Others, from the Beginning to the Civil War. New York: F. Ungar Publishing Co., 1965.

Penley KnipeAssistant Conservator of Works of Art on Paper

Straus Center for Conservation

Harvard University Art Museums

Publication History

Received: Fall 1999

Paper delivered at the Book and Paper specialty group session, AIC 27th Annual Meeting, June 8-13, 1999, St. Louis, Missouri.