Historic Intent: Lodovico Ughi's Topographical Map of Venice; A Large Wall Map as an Historic Document, a Work of Art, and a Material Artifact

by Susan FilterIntroduction

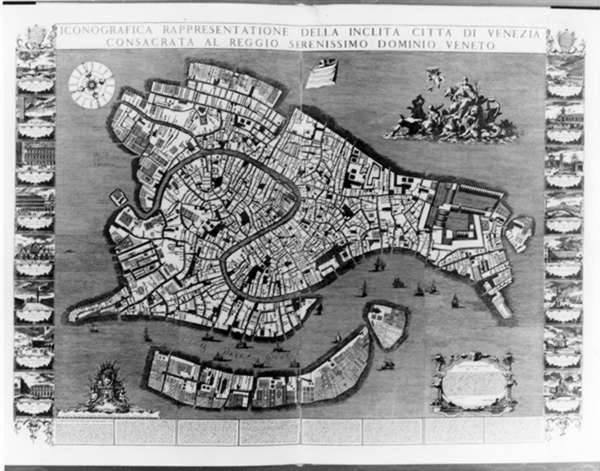

Fig 1. Ughi Topographical Map of Venice

The Ughi wall map of Venice measures about 5 feet by 6 feet (1480 x 2635 cm.), is printed from twenty copper plates on thirteen sheets, and is flanked by sixteen views of Venice (Figure 1). My interest in the Ughi Map was sparked when I performed conservation treatment on a copy of the map while living in Venice a few years ago. Its condition intrigued me. It was mounted on heavy white cloth, apparently recently, and despite the water damage to the bottom edge, it was in fairly good condition for a map printed in the eighteenth century.

Eight copies of the map were located in Venice in public and private collections and their present conditions and formats were studied. The conditions exhibited in these maps are typical of those we find in other old large maps. Large maps have always been problematic to display and store. By the very nature of their size, many have perished. If an old large map has survived the ravages of time, it is most likely not in its original format. Typical alterations involve removal of hanging devices such as dowels, sectioning and trimming, removal of cloth mounts, and the addition of varnish coatings.1

One of the purposes of this paper is to highlight some of the more subtle qualities of cultural and artifactual significance in large maps that are frequently overlooked. In order to prepare an appropriate treatment plan, a conservator must appreciate the intrinsic value and the historical significance in the context of an artifact's use.

This paper is the result of research I conducted in Venice in 1992 with the help of a grant from the Gladys Kreible Delmas Foundation. The grant allowed me to study in depth Lodovico Ughi's large topographical map of Venice, first printed in 1729, as an historical document, a work of art, and as a material artifact.

The Importance of the Ughi Map as a Cartographic Document and as a Work of Art

A. Venetian Map Making

Lodovico Ughi's topographical map of Venice is a landmark in the cartographic history of Venice. Over the centuries, Venetian map makers in general copied one another and did not significantly alter the appearance of the city from year to year. Among the exceptions are Jacopo de Barbari's magnificent bird's eye view of Venice printed in 1500 and Ughi's map of 1729. Not only are they the two the largest printed maps of Venice, but they served for centuries as models for all subsequent plans made of the city.

The bird's eye view depicted a city from a high oblique angle, enabling the cartographer to convey the vertical dimension of the buildings and architectural features of the city, while at the same time retaining a horizontal dimension, which relied on perspective rather than true scale. The intention was to impress the viewer.

The advancements in science and technology in the eighteenth century improved the surveying and measuring techniques used by urban cartographers who produced works progressively more accurate and functional. By the 1730's bird's eye views no longer matched the standards of accuracy expected of urban surveyors who were now commonly depicting towns by means of a less decorative but more precise ground plan, the topographical map.

The Ughi map is the first and still largest topographical map produced of Venice based on accurate field surveys rather than on observation and copying of existing maps. Republished twice again during the century,it became the basis of all later topographical representations of the city, down to the fall of the Republic in 1797. Through its copies and subcopies, it dominated the field of Venetian map making well into the nineteenth century.

Unfortunately, very little is known about Lodovico Ughi, the cartographer, or the etcher of the map portion. However, there is information on Venetian map making at the time. The Ughi map was produced shortly after Fra Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718), the official geographer to the Venetian Republic, founded the first Society of geographers called the Academia degli Argonauti in 1680. Coronelli, the eminent cartographer of his time, was prolific publishing numerous maps, nautical charts, and the largest sets of globes (15 feet in diameter) of the time.2

B.Iconography and Printed Information on The Ughi Map

Images on maps can be as important as the geographical information since they inform viewers of architectural splendors and the wealth of a city, as well as its political, commercial, and military greatness.

At the time of the printing of the Ughi map, Venice had been an independent republic for almost 1000 years during much of which she had been mistress of the Mediterranean, the principal cross roads between East and West, and the richest and most prosperous commercial center in the civilized world. As Jan Morris said, 'no nation has ever presented itself with more panache, confident as the Venetian Republic was, almost to the end of its independent history that it would last forever. Coupled with this conceit, were a highly calculated love of ceremony and a gift of publicity.'3

The Ughi map is nothing less than an advertisement for the beauty, military might, and prosperousness of Venice. The title itself announces it: "Iconografica Reppresentazione della Inclita Citta` di Venezia al Reggio Serenissimo Domino Veneto" (Topographical Representation of the Glorious City of Venice Consecrated in the Reign of the Most Serene Veneto Domaine). Flanking the map portion eight on each side, are sixteen beautiful views of the city of Venice. Views of the city were included because the new planographic type of map now lacks the famous landmarks, attractions, and depictions of fortifications of the bird's eye view maps (beauty, affluence, and military might).

At the bottom left around the shield of the Morosini are seen putti holding, flags, pikes, and staffs - triumphal war articles. Francesco Morosini, the last of the warrior Doges, led the battle against the Turks in the War for Candia or Crete which was lost to the Venetians after 465 years of occupation in 1669. This symbol would not have been lost on Europeans of the time. The siege of Candia lasted for twenty-two years in which the Venetians, though from time to time aided by European allies, stood alone in the defence of the town and the encroachment of the Turks into Western Europe.

At top right is the depiction of an allegorical Venice, triumphantly sailing on the sea pulled by dolphins, sea animals, and divinities, with the lion of St. Mark at her feet, symbolizing her marriage to the Queen of the sea and the riches she derives from it. St. Mark is the patron saint of Venice.

At the top left of the map, is the Vitruvian windrose, each wind direction personified by the head of a putti, and the eight major points of the compass, important for a city dependent on seafaring trade.

In the cartouche at the bottom right, is a dedication by Lodovico Ughi Alvise Mocenigo, the Doge in 1729. He expounds on '...the glorious city of Venice, blessed by the Virgin, divine, Queen of the Adriatic, always envied, a constant sustainer of the Catholic religion, known throughout the world for her justice, feared by her enemies, defended in all times by her sons who have sacrificed their lives, ..., your most humble servant Calviai. Lodovico Ughi.'

Because of the large scale of the map, for the first time place names are directly on the map, rather than using reference letters or numbers correlating to a text below. To distinguish urban elements, the streets are depicted with parallel lines, the religious buildings have closer parallel lines and letters, and the rios and canals are shown by wavy lines. The civic buildings are left in white.

C. The Work of Art

Once the printing press was introduced, the Venetians were among the first to use it for the printing of maps. Venice, as a mercantile center, received new cartographic information from all parts of the world. The maps produced served not only Venetian outposts, but travelers, students, and men of state and war. By the eighteenth century, conditions in Venice were ideal for a thriving market in print making. Professional engravers and book illustrators were very active and turned out an abundant production, and prints were an easy product to transport, handle and export.

The importance of the printed Ughi map in eighteenth century Venetian culture cannot be underestimated. The publishers, engravers, and artists involved in its creation were some of the most talented and prolific of their time.

The first publisher of the map, Giuseppe Baroni, was one of a group of six Venetian printmakers and merchants who in 1718 formed a guild of engravers called L'Arte degli Incisori, in an attempt to regulate the quality of the art of copper engraving and to have the exclusive rights to their production. His workshop, or bottega, was located in Campo S.Zulian, near Piazza S. Marco, where most of the printers were concentrated.4

When Baroni died, records show that the copper plates of the Ughi map were among those listed in the inventory for his bottega. The second publisher of the map, Lodovico Furlanetto, acquired them when he bought the entire inventory from the estate of Baroni. Furlanetto printed it for at least sixty years after substituting his own name in the lower right corner.5

Fig. 2. Flanking View of the Piazzetta from the Ughi Map, possibly by Francesco Zucchi, directly copied from Carlevarijs

Though not conclusive, stylistic evidence points to the hand of Francesco Zucchi as the engraver of the sixteen views of Venice which flank the Ughi map (Figure 2). Zucchi, a member of Baroni's guild, was a prolific book illustrator. The prints of the views, more refined, are directly copied from Luca Carlevarij's, famous Fabriche e Vedute di Venetia, published in 1703 (Figure 3). Carlevarij was one of the famed Venetian "vedutisti" or view painters.

Fig. 3. View of the Piazzetta engraved by Luca Carlevarijs from the series "Fabriche e Vedute di Venetia."

Fig. 4. Drawing of "Venezia Trionfonte" by Sebastiano Ricci from Zanetti album.

Fig. 5. "Venezia Trionfonte" from the top right of the Ughi Map.

Recent studies have uncovered a drawing of Venezia Trionfonte (Figure 4) by Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), an acclaimed Venetian painter, that can now be established as the preparatory drawing for the allegorical figures in the upper right of the Ughi map (Figure 5). The drawing is in album #56 from the library collection of Anton Maria Zanetti (Academia Gallery,Venice), a friend and patron of Sebastiano and Marco Ricci.6

Analysis of Conditions, Storage, and Formats of Ten Ughi Maps

While researching in Venice, eight copies of Ughi's topographical map were located and examined. Six copies were photographically documented. The maps were in various collections: libraries, museums, and private. The collection type I believe predetermined, in many cases, the format, housing solutions and conditions of the maps. Of course, the era when the maps were added to the collections is also a factor.

When examined, the present conservation conditions of the Ughi maps were noted: patterns of deterioration, repairs, subtractions, additions, etc. Because the maps' large size made it problematic to store, the various solutions for housing and storage varied greatly as they evolved over a three hundred year period. From this information we can better understand how the various conditions in which the maps were found were affected by housing, storage, and format. Also, we should keep in mind the limitations on collection care in institutions and private collections.

Fig. 6. Hanging wall map in the background of a Jan Vermeer Painting.

The intended format of the Ughi map would most likely have been like the map in the painting by Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) The Painter in his Studio: lined on cloth and attached to dowels at the top and bottom, and meant to hang on a wall (Figure 6). During my research, I did not see any copies of the Ughi map in this format, nor any old, large sized map in Venice, for that matter, in this format.

If a map is used in the hanging format, unless it is kept and handled in the gentlest way, it won't survive in this state over an extended period. The dowels tear away, the adhesive between the paper and lining fails, and the materials are damaged by the environment, insects, handling, and rolled storage.

Eight Copies of the Ughi Map

1. Camerino Map

The Ughi map I treated in 1986 was rolled when I received it for treatment. It was lined on white cloth with water soluble adhesive that had not discolored. The map had been mounted, I believe, within the last 20 years, as evidence in the clean, white cloth backing the map. The rusty nail holes around the perimeter of the cloth indicated it had been mounted on a stretcher at one point. The damage on the map consisted of a very large water stain at the bottom edge, a yellowed varnish coating, numerous horizontal creases from being rolled, and many edge tears. Much of the damage was due to its storage in the rolled state.

The conservation treatment consisted of surface cleaning, backing removal, varnish removal, washing, and mending. The quality of this 18th century paper was magnificent. It was not lined at the request of the client.

The client had the map framed at his residence. There are no spacers between the frame and the glass. The glass, large and heavy, is presently bowing in and squashing the center of the map. The framed map is tremendously heavy, it will be very difficult to move, when the time comes, from its location on the top floor of a Gothic palazzo.

2. Cooley Map

This version of the map remains unmounted. The individual sheets are sewn in a volume, probably by a collector. There are remnants of leather and a handwritten label on the spine. The cover is missing.

Each printed sheet is folded into a folio, which is guarded and tipped into the book along the center fold with adhesive.

The guards are sewn and glued into the binding. There are no sewing holes on the plates.

Some sheets have only one plate, others have two plates with dotted lines showing were to cut them. Except for a few minor stains, a few creases, and some minor handling grime, the prints are in excellent condition.

This particular copy of the Ughi map answered one of my first questions about the map I treated a few years ago (the Camerino map), that is, why the backing was new and the damage recent. The obvious answer is that the printed sheets of the map are left unmounted until they are purchased, a very practical solution for storage.

3. Palazzo Ducale Exhibit Map

This Ughi map is in a long-term exhibition at Palazzo Ducale about Venice. It has been cut into 24 pieces, not always evenly, and not following the maps real sections, and lined on linen. There is a crease in the cloth between the sections which indicates that it had been stored folded. This is a typical solution for storing large maps in libraries, sectioned and lined, they can be folded and stored in drawers, or in boxes on a shelf. The map's condition was quite good, though it has been trimmed at the edges. It appears to have received conservation treatment. It had little surface soil and there were a few shiny spots, which appeared to be the remnants of varnish that had been removed. There were also bits of blue ribbon and sewing holes on the outer edges of the map from an older mount.

4. Marciana Library Maps

There are two Ughi maps in the collections at the Marciana Library. The first one is in the map collection and is heavily used by researchers. It is in the same format as the map at Palazzo Ducale, sectioned into 24 pieces and mounted on cloth. It is folded and has a cardboard portfolio cover and is housed in a paper slip cover. The map is in shabby condition. It has severe damage from handling. The paper is soft, there is abundant surface grime, it is mottled with purple mold spots, there is abrasion to the printed ink surface from all the opening and closing of the map, and there are losses and tears at the edges of each section. There are also many large areas of detachment between the cloth and paper. Obviously the map will continue to be damaged in this format and from the heavy use it receives from researchers.

5. The second map at the Marciana

The second map at the Marciana is the only copy I saw which was published by Giuseppe Baroni. The Baroni copies are rare because fewer were published by him, though all copies of the Ughi map are also considered rare. It is stored framed hanging in a hallway between the stacks next to a copy of the famous Jacopo de Barbari map of Venice, which is in a poor state. There is no climate control in this section of the library.

This map is severely damaged. It had been previously mounted on cloth, the evidence in the sewing holes at the sides. The cloth has been removed, it is sectioned into eight pieces and adhered overall to an acidic paper board, and varnished. It is framed not under one piece of glass, but three sections of glass, which are scotch taped together at the joins. From the style of the frame and the lettering on the title, my guess is that it was mounted this way at the end of the 19th century.

The paper and printing completely lack character from the mount application, which has given it a pressed and plastic appearance. The varnish coating on the map is darkened and crazed. There is water damage at the bottom edge (which appears as a typical damage on these large maps) resulting in tide lines, stains, mold spots, and areas of detachment between the backing and the map. The upper left corner is radically darker than the rest of the map, perhaps this section of glass had been broken and was exposed for a long period of time before it was replaced. The glass is extremely dirty and there is debris, dirt and insect nests between the glass and the map. There is loss to the map surface from silverfish and abundant fly specks scattered throughout.

6. Museo Correr Maps

The framed format is one solution (not that the Marciana example is good) for storage of oversized maps. This is the solution that the Museo Correr has chosen for their large collection of oversized maps. All are framed (some matted) without hinges, with glass glazings, and hung on the top floor of the museum in the storage area. There is no heat or cooling on this floor. The objects are periodically checked for condition change. In frames, the maps can't be handled by researchers and are always ready for exhibition.

There are two Ughi maps in the collections of the Museo Correr. Both copies are framed. One copy, hanging in the director's office, is lined with what appears to be its original eighteenth century cloth backing. The paper has a worn appearance. There is red ink on the map outlining some buildings and canals. There is some planar distortion and some creases. The map, according to the Director, has not received conservation treatment.

7. The other copy of the Ughi map is stored, resting on the floor, in the storage area. It is used often in exhibits in both Venice and abroad. There are a few water stains at the bottom edge. The only conservation treatment it has received is a light surface cleaning.

8. Rocca Map

This Ughi map is in a private collection and has belonged to the family for at least 75 years. It is framed and now hangs at the top of the stairs in the entryway of the family palazzo. It has only been framed for a few years. It used to hang unprotected at the bottom of the steps nearer the doors.

The map is lined on a rough cloth, which appears to be an original eighteenth century mount. It is missing the top and bottom sections and, more importantly, the flanking prints of the views of Venice. The prints may have been removed for their decorative value, or because the paper was damaged at the edges and it was trimmed. This map has also been marked with red ink, as is one copy at the Correr.7 There is varnish coating, which has slightly darkened. There are the ubiquitous water stains at the top right and the bottom center, along with various other stains. There is a large split at the top center, and smaller ones scattered throughout, probably from the different expansion rates between the cloth and the paper. There are also numerous wrinkles and creases in the paper. There is severe silverfish damage at the edges of the map and at the splits. I wondered if framing the map encouraged silverfish damage in that it gives them a nice micro environment to live in.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to highlight some of the qualities of cultural, historical and artifactual significance that can be overlooked in a large map.

Conservation treatment is conducted within the historical context of an object. The challenge to the conservator is to recognize and preserve the historically significant features of an object. Paradoxically these features often reside in apparently inconsequential aspects of an artifact - surface dirt, old backings, and hanging devices.

In the course of this investigation we found that the condition, use, storage and care have also had an impact on the appreciation of this artifact today.

It is significant that no examples were found that reflect what I believe to be an original mounting with dowels still attached. In fact, the copy in the best state of preservation was the bound unmounted copy. It not surprising that time has sharply heightened the contrast in the effects of the care of an oversize, unusual format item such as the Ughi map. It is worth noting that mounting continues to exact a cost in wear and long-term preservation on an object after this stage of physical treatment. I found that the mounted maps that had fared the best were those that had the least intervention, specifically those in the Museo Correr Collection.

Through sensitivity to the cultural, historical and artifactual significance of the artifacts we receive for treatment, conservators become more fully aware of the consequences of their role, and can make better informed decisions for treatment and recommendations for care.

Notes

1. Anecdotal evidence suggests that varnishing paper maps is a nineteenth century preservation technique.2. When Coronelli died, his papers were sold as scrap and his copper plates for the value of the metal).

3. Morris, James. The World of Venice. Pantheon Books, New York,1960.

4. Baroni's bottega is now the address of Cartier.

5. Furlanetto also published some of the most beautiful and famous views of eighteenth century Venice, Canaletto's "Feste Pubbliche di Venezia," engraved by Brustolon (1768).

6. Zanetti, an engraver and art historian, was the first inspector appointed by the Council of the Inquisition to uphold the law that no important artwork could be restored or exported without permission.

7. In 1937, a new canal was cut through this area to make access to Piazzale Roma where the bridge from the mainland reaches Venice. Anecdotal information suggests that the Ughi map was used up until recently by engineers and architects in Venice, if they were lucky to have a copy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Gladys Kreible Delmas Foundation for supporting my research in Venice, Christopher Cooley, Max Rocca, Carlo Maria Rocca, and Ugo Camerino for allowing me to study their maps, and Francesco Mirate for his many kindnesses, camera and bibliographic information.

References

Bettagno, A."Precisazioni su Anton Maria Zanetti il Vecchio e Sebastiano e Marco Ricci." Estratto da: Atti del Congresso Internazionale di Studi su Sebastiano Ricci e il Suo Tempo, Udine, Maggio, 1975.

Civici Musei Veneziani D'Arte e di Storia. Bolletino, 1980-XXV N.S. n.1-4.

Cassini, G. Piante e Vedute Prospettiche di Venezia (1479-1855). La Stamperia di Venezia Editrice, 1982.

Gallo, R. L'incisione nell '700 a Venezia e a Bassano. Venezia, 1941.

Norwich, J.J. A History of Venice. Penguin Books Ltd., England, 1983.

Pittaluga, M. Acquafortisti Veneziani del Settecento. Casa Editrice Le Monnier, Firenze, 1952.

Romanelli, G. Venezia tra Oscurita` degli Inchiostri, Cinque Secoli di Cartografia. Venezia, 1989.

Succi, M. Da Carlevarijs ai Tiepoli, Incisori Veneti e Friulani del Settecento. Gorizia-Venezia. Albrizzi Editori, 1983.

Schultz, J. "The Printed Plans and Panoramic Views of Venice (1486-1797)." Saggi e Memorie di Storia dell'Arte, n.7 Venezia, 1970.

Susan FilterConservator

Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

Publication History

Received: Fall 1994

Paper delivered at the Book and Paper specialty group session, AIC 22nd Annual Meeting, June 11, 1994, [PLACE].

Papers for the specialty group session are selected by committee, based on abstracts and there has been no further peer review. Papers are received by the compiler in the Fall following the meeting and the author is welcome to make revisions, minor or major.