Safety in the Laboratory

Foundation for Advancement in Conservation

© 2008

Introduction

All chemicals, however common or innocuous, have inherent dangers. Ingest too much salt, NaCl, and you will be ill. You can drown in two inches of water.

The chemicals we use in conservation labs, however, need careful handling and special precautions. To mantain a safe work environment and safe work practices, you need to be aware of the risks and precautions you should take.

Contents

There are several ways to take in chemical substances:

This tutorial covers each route of exposure, the associated precautions, and other sources of information.

Please complete each section in order, as the information builds on that covered in previous sections. You can return to any section later.

Press Ctrl+Shift+F to search.

Learning Objectives

After completing this tutorial, you will:

- Be aware of the routes of exposure to chemical substances, including inhalation, ingestion, through skin damage, and absorption

- Know that the only way to reliably identify what is in a chemical container is to make sure that it is properly labeled

- Understand that long-term exposure to small amounts of a chemical can cause an undesirable reaction

- Know some of the resources for safety rules and procedures that should be available in your lab

- Have a basic set of behavior rules for the lab

Inhalation

Inhalation applies to breathing in vapors. Any solvent vapor with a molecular weight greater than nitrogen gas (28) will sink to the floor and remain there. Just because you can't smell it doesn't mean that it isn't around.

For example, the molecular weight of:

| Hexane | 86 |

| Toluene | 92 |

| Acetone | 58 |

| Ethanol | 46 |

Anyone who sniffs a colorless liquid "to see what it is" is asking for a very unpleasant, and potentially dangerous, result.

Label Everything, Including Water

What's in this beaker?

Assuming that anything unlabeled is water is asking for trouble.

A beaker of colorless liquid could be anything, and there is no easy way to find out.

The Conservation Wiki has a guide to labeling chemicals.

Ingestion

Apart from actually drinking the chemical, many substances can be "ingested" through the:

- Eyes

- Nasal passages

- Lips

- Tongue

- Thin skin inside the mouth

Anyone who has cooked with jalapeño peppers knows how easy it is to get them in the eyes and mouth from their fingers.

Long Time Exposure

Don't assume that small amounts of exposure will not hurt you.

Over time you can make yourself hyper-sensitive to that particular chemical.

Getting a blinding headache every time you even go near one of the common solvents in your field is a surefire way to put a damper on your career.

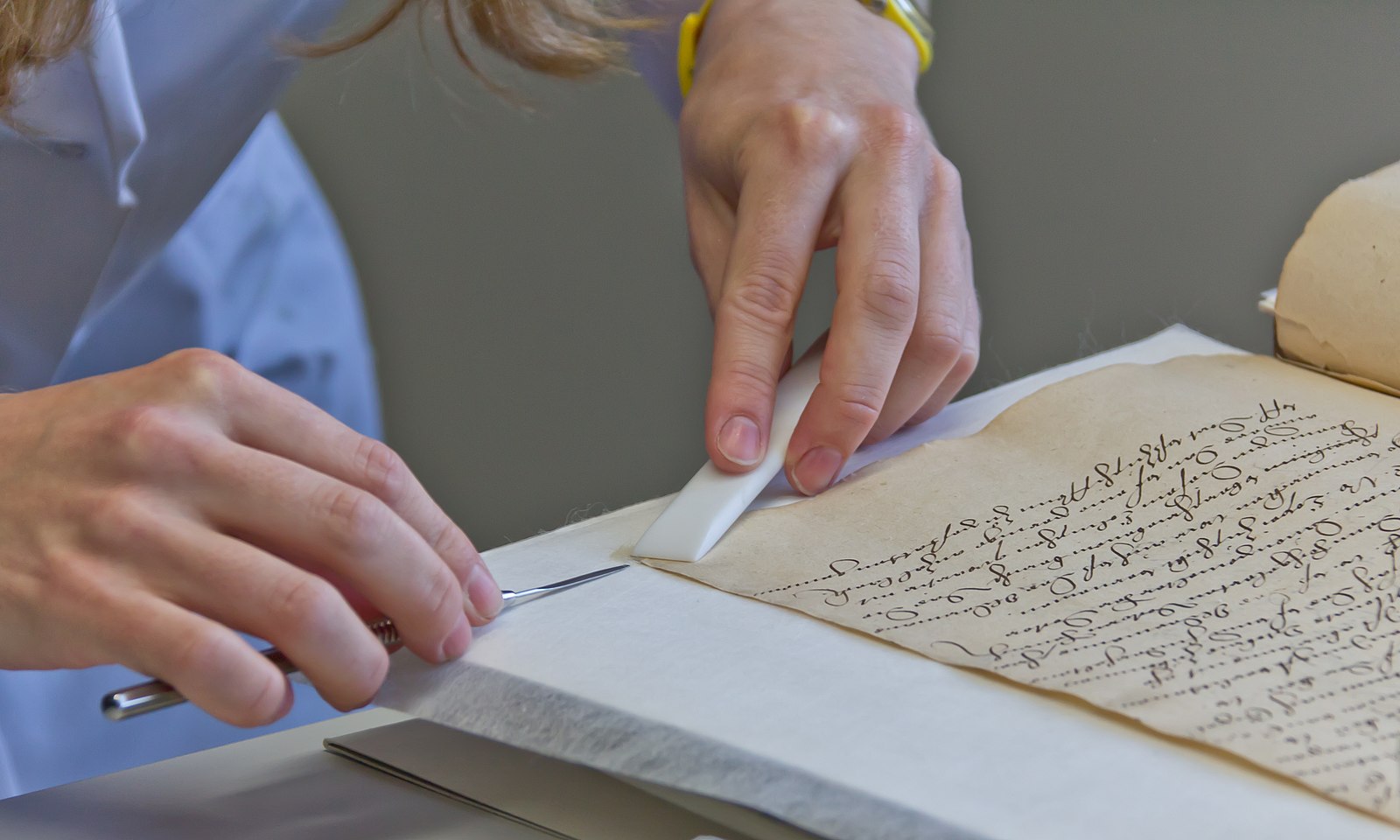

Damage to the Skin

Practicing conservators are constantly getting tiny cuts and scrapes on their hands, especially around the nails and ends of the fingers where chemicals can get behind the skin barrier.

Getting chemicals under your nails and scratching your face has a similar result.

Skin Absorption

It is a fallacy to assume that the skin is a barrier to everything.

Many chemicals will enter your body through the skin.

Think nicotine patches.

Chemical Hygiene Plan

All laboratories should have a chemical hygiene plan and the staff should have signed to confirm they have read it.

It should be regularly updated (at least once a year) and someone in the lab should be responsible for it.

Information on what it should contain, the subject headings, and some model plans that you can follow are available on the AIC Wiki at Set Up for a Safe Space: A Chemical Hygiene Plan.

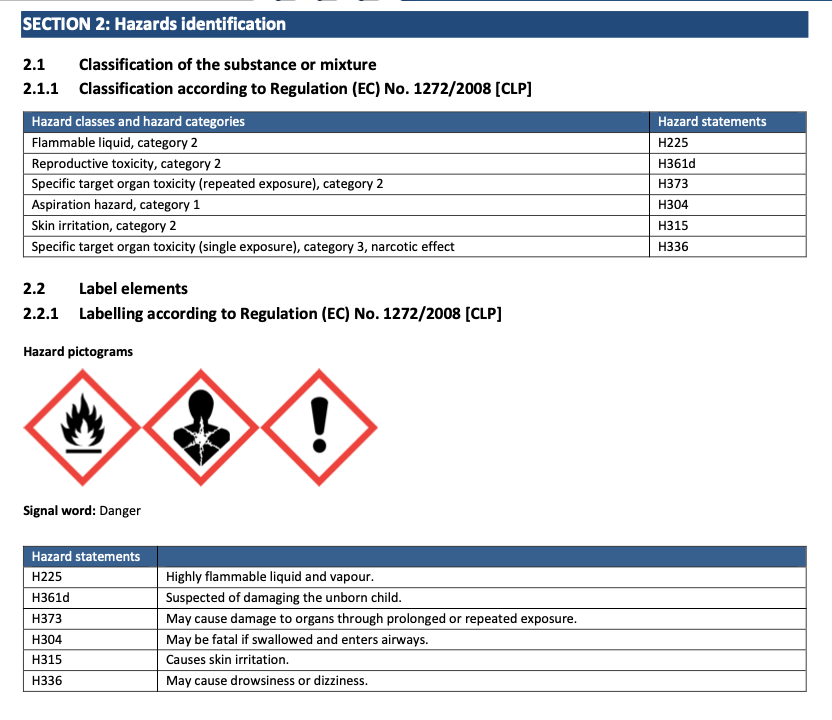

MSDS

Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) should accompany any chemical that you buy and may be available on the manufacturer's website. There will also be an MSDS for commercial products such as Beva 371 or Paraloid B72.

There is help on reading an MSDS on the AIC Wiki.

International Chemical Safety Cards

A far more user-friendly version, that contains all of the safety information for each chemical (but not commercial products), has been published by a collaboration between the International Program on Chemical Safety and the Commission of European Communities, International Chemical Safety Cards

NIOSH Pocket Guide

NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety) has published a Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards.

In addition to specific chemicals, the appendices contain additional information on occupational carcinogens, respirator types and requirements, first aid, and other topics.

Lab Rules

And finally, some of the basic rules of behavior in the lab:

- Take it slowly. Don't rush or run in the lab.

- Don't eat or drink in the lab.

- Keep long hair, jewelry, and loose, flapping clothing to a minimum.

- Wear sensible closed-toe shoes, not sandals.

- Wear protective clothing.

- Follow OSHA guidelines.

- Label everything.

- Find out where the safety shower, eyewash, and spill kit are.

- Use the extraction equipment.

- Read the chemical safety sheets before you start.

Laboratory Safety: Summary

In this tutorial you learned:

- The routes of exposure to chemical substances, including inhalation, ingestion, through skin damage, and absorption

- That the only way to reliably identify what is in a chemical container is to make sure that it is properly labeled

- That long-term exposure to small amounts of a chemical can cause an undesirable reaction

- Some of the resources for safety rules and procedures that should be available in your lab

- A basic set of behavior rules for the lab

References

These articles on laboratory safety can be found at JAIC Online.

Credits

Researched and written by Sheila Fairbrass Siegler

Instructional Design by Cyrelle Gerson of Webucate Us

Project Management by Eric Pourchot

Special thanks to members of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation (ANAGPIC) and the AIC Board of Directors for reviewing these materials.

This project was conceived at a Directors Retreat organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and was developed with grant funding from the Getty Foundation.

Converted to HTML5 by Avery Bazemore, 2021

© 2008 Foundation for Advancement in Conservation