Relative Humidity

Foundation for Advancement in Conservation

© 2008

Introduction

A thorough understanding of relative humidity, and the ability to explain it to non-conservators, is necessary for environmental monitoring and artifact preservation.

This tutorial does not attempt to examine the effects of differing relative humidity on specific materials, but it does cover the general basic concepts of relative humidity.

Before working through this tutorial read the sections on states of matter in the AS and A Level Chemistry Through Diagrams (Oxford Revision Guides) or a similar basic chemistry book.

Contents

In this tutorial, you will learn:

- That steam, like many other gases, can't be seen by the human eye

- How water evaporation and condensation are related to temperature and pressure

- That relative humidity is really a measure of relative vapor pressures

- What the dew point represents

- How relative humidity is measured using a sling psychrometer

- How to use a psychrometric chart

Please complete each section in order, as the information builds on that covered in previous sections. You can return to any section later.

Press Ctrl+Shift+F to search.

Definition

We all know the equation:

\(\text{Relative Humidity} =\ \frac{\text{Amount of water vapor present in the air}}{\text{Amount of water vapor that could be} \\ \text{present in the air at that temperature}} \times \ 100\)

So far, so simple but...

Water Vapor

Water vapor is a gas. It is the gas phase of water and we could equally refer to it as water gas, like nitrogen gas.

Unfortunately very hot water vapor is also, technically, called steam. This can cause confusion because what we commonly think of as steam is actually condensed water droplets, or mist. We can't see water vapor (or steam), any more than we can see oxygen.

Water Vapor

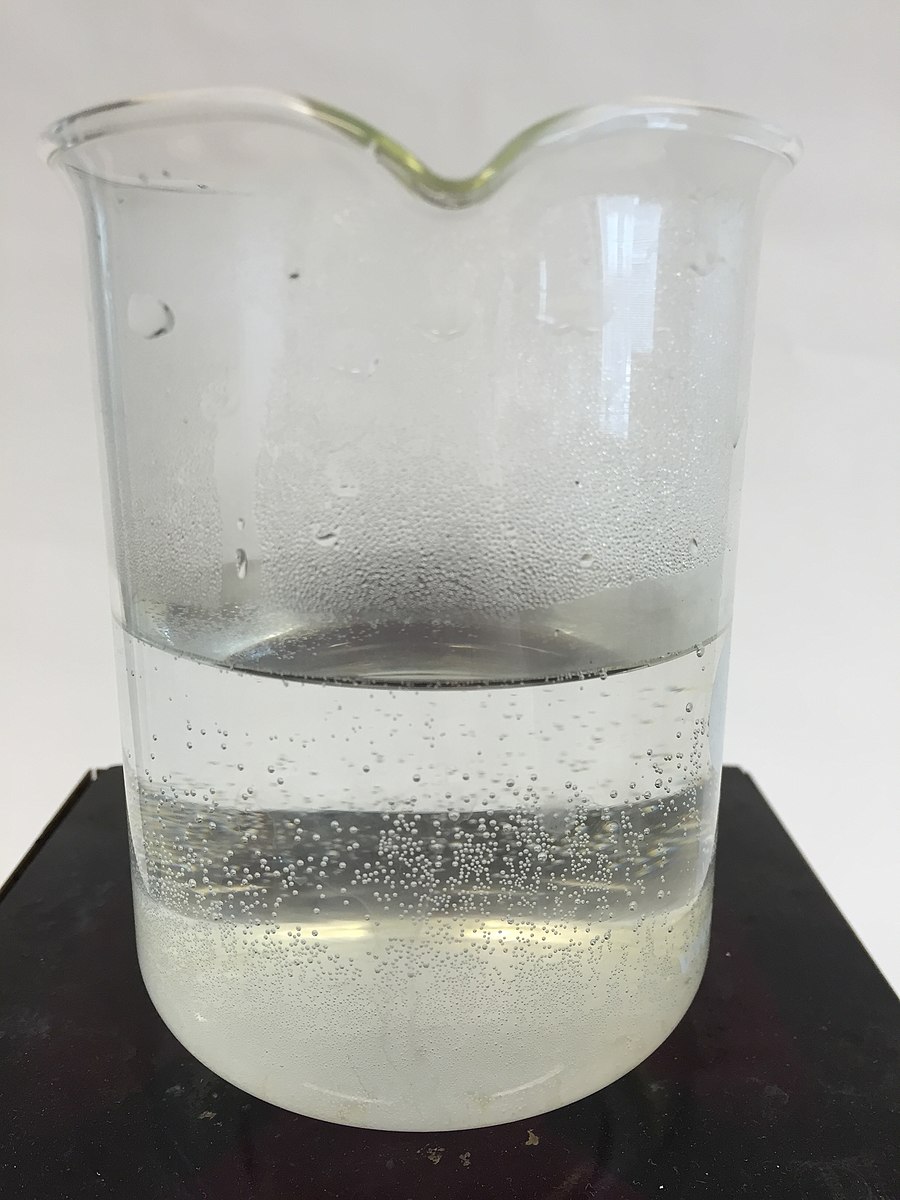

The top of the beaker has condensed water droplets.

The tiny area just above the surface, before we can see the white condensation, is steam.

The bottom contains boiling water.

Why Water Evaporates

So why would water evaporate from a nice, stable, liquid state to become a gas if it is below 100ºC?

It's all to do with temperature and pressure.

Effect of Temperature

Water molecules in a liquid state are attracted to each other through hydrogen bonding.

These bonds are not static. They can break and form very quickly (~10-15 seconds) and the water molecules can move around each other.

The speed at which the water molecules move is determined, to a large extent, by the temperature. The higher the temperature, the more energy there is in the system and the faster the molecules will move.

Evaporation

Water molecules can also transfer energy between each other when they collide.

As the temperature of the air above the water surface rises, water molecules at the surface can get enough energy to evaporate.

Effect of Higher Air Temperature

Warmer air however does not "hold" more water vapor, any more than it "holds" oxygen or nitrogen.

Instead, at a higher air temperature there is more thermal energy for water molecules to exist as a gas rather than a liquid.

Ideal Gas Law

So, if the water molecules are now a gas, rather than a liquid, they must obey the ideal gas law (well, as much as anything else does). The ideal gas law relates pressure to temperature.

\(\textbf{Pressure} =\ \frac{\text{A Constant }{\left( 8.314 \text{ JK}^{-1} \text{mol}\right) }\ \times \ \textbf{Temperature (in Celsius)}}{\text{Volume of Gas}}\)

For the moment, let's assume that the whole of the Earth's atmosphere behaves like an ideal gas. If we keep the volume of gas constant (not difficult when thinking of the atmosphere) then if the temperature rises, the pressure will go up.

Gas and Pressure

All gas has pressure.

If you stand at the sea shore you have around 14 pounds per square inch of gas pressing down on your head.

Absolute Humidity

The saturation vapor pressure of water is reached when the number of water molecules evaporating from liquid water is equal to the number condensing back out of the atmosphere.

Rate of evaporation = Rate of condensation

This is what we term absolute humidity.

Arden Buck Equation

The saturation vapor pressure is calculated from the Arden Buck equation.

\( P_w = 6.1121 \exp \left( \frac{t \left( 18.678 - \frac{t}{234.5}\right) }{257.14 + t} \right) \)

Notice it's all about temperature.\(P_w\) is the saturation vapor pressure of water

\(\exp\) is the exponential function

\(t\) is the air temperature in degrees Celsius.

Relative Humidity

So instead of talking about water vapor in the air we should, more truthfully, be saying:

\(\text{RH} = \frac{ \text{Actual Vapor Pressure}}{\text{Saturation Vapor Pressure}} \times 100\% \)

Vapor Pressure Over a Temperature Range

The saturation vapor pressure (dew point) can be calculated over a range of temperatures

Notice that the vertical scale is weight/weight.

\(\frac{\text{Weight of water vapor (g)}}{\text{1 kilogram air}}\)

Dew Point

- If the humidity has reached the saturation vapor pressure,

- and the amount of water vapor in the air remains the same,

- and the pressure remains the same (which it will do if we are at atmospheric pressure),

- but the temperature drops,

- then some of the water vapor will condense out of the air and onto surfaces as liquid water,

- because there is less energy in the form of heat to hold the water in its vapor phase.

100% RH over a Temperature Range

Measuring Relative Humidity

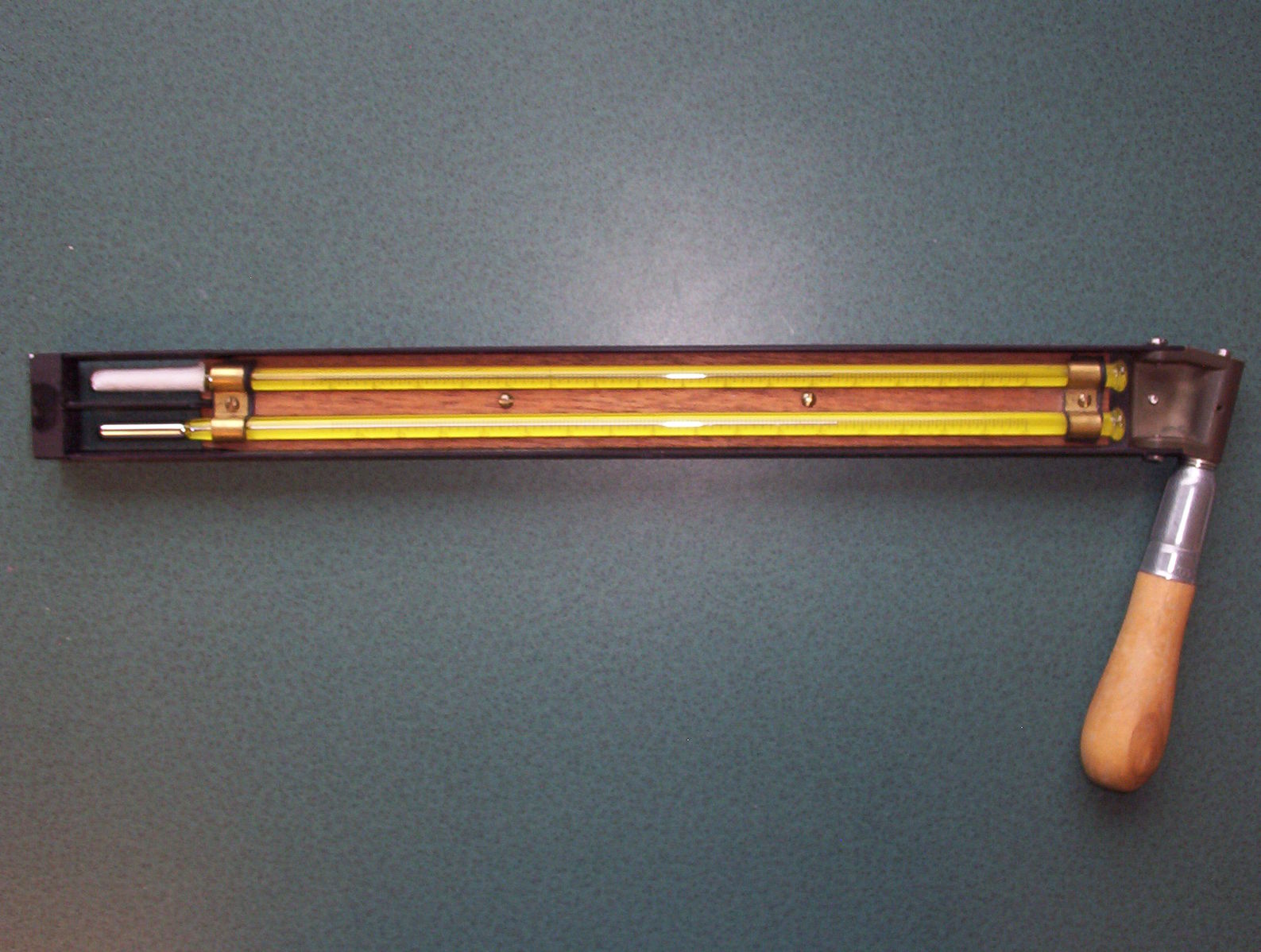

One of the simplest, and possibly most accurate, ways of measuring relative humidity is with a sling psychrometer.

This simple piece of equipment has two thermometers. One is kept wet and the other dry. By comparing the two different temperatures between the two thermometers it is possible to calculate the relative humidity.

When measuring relative humidity, you should always take more than one measurement (at least 3 if possible) and then find the average.

Psychrometric Chart

The relative humidity scale goes up the side and across the top.

Using the Psychrometric Chart

Here the wet bulb temperature is 56.3ºF (13.5ºC) The dry bulb temperature is 68ºF (20ºC)

Find the point where they intersect, and follow the curved line up to the relative humidity axis.

The RH is 50%.

If you follow the straight line from the intersection point back to the left axis you will find the dew point temperature for that RH. At RH 50% the dew point is 48.7ºF (9.3ºC).

Summary

In this tutorial, you learned that:

- That steam, like many other gases, can't be seen by the human eye

- How water evaporation and condensation are related to temperature and pressure

- That relative humidity is really a measure of relative vapor pressures

- What the dew point represents

- How relative humidity is measured using a sling psychrometer

- How to use a psychrometric chart

References

These articles on relative humidity can be found at JAIC Online.

Credits

Researched and written by Sheila Fairbrass Siegler

Instructional Design by Cyrelle Gerson of Webucate Us

Project Management by Eric Pourchot

Special thanks to members of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation (ANAGPIC) and the AIC Board of Directors for reviewing these materials.

This project was conceived at a Directors Retreat organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and was developed with grant funding from the Getty Foundation.

Converted to HTML5 by Avery Bazemore, 2021

© 2008 Foundation for Advancement in Conservation